- Accueil

- > Shakespeare en devenir

- > N°14 — 2019

- > Introduction

Introduction

Par Estelle Rivier-Arnaud

Publication en ligne le 13 novembre 2019

Table des matières

Texte intégral

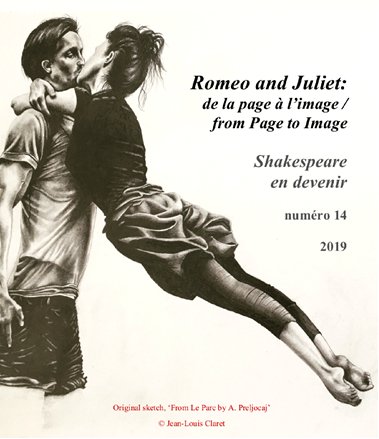

Original sketch, ”From Le Parc by A. Preljocaj”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

1Why is the star-crossed Veronese couple still so attractive today? For not only stage-directors and filmmakers have used the Shakespearean source and contextualized the plot in often daring ways, but also bloggers and Youtubers, manga and comic-book designers, novelists and storytellers, composers for operas and ballets, musicians and dancers, painters, and illustrators. All have been inspired by the tragic passion that Shakespeare poetically conveyed in the 16th century. And all contribute to a prevailing sense that, of all Shakespeare’s plays, the imagery of Romeo and Juliet is not only the most deeply imprinted in the global imagination, but particularly photogenic in a way that (im)perfectly aligns with today’s hyper visual culture.

2This collection of essays reassesses the attraction of this play in a range of studies that tackle adaptations on stage, screen, and page, and as standalone image. While far from exhaustive—new media appropriate and disrupt the meaning of Romeo and Juliet more briskly than ever—the essays nevertheless provide new readings of both established and under-examined works. Amidst the unending proliferation of scholarly works on the play, the present volume focuses especially on the artistic images that convey new visions and relocate the text in new media. These images are a way for us, scholars, readers, film, and theatregoers, to embed Shakespeare’s lines in our minds with new animation; and they are a way to keep the story alive, interrogating questions of our own time: how new ideologies and policies may be treacherous, how tensions and conflicts in love as well as in society can be apprehended by past (his)stories.

3To account for these idiosyncratic visions that the artists of our time have left, twelve essays and “varia” comprise the volume. They have been divided into four sections: stage, screen, music, and graphic arts.

4The first section begins with Laureano Corces, “Some Hispanic Versions of Romeo and Juliet Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Montesco y su señora, Nacahue, and Romeo and Juliet in a Jewish Version”, focusing on Latin American works and evaluating how Shakespeare’s tale of romantic love is shaped by the circumstances of the individual in these Latin societies. Corces explores how revolutionary Cuba, the Ecuadorian bourgeoisie, the Cold War scenario, and other political settings inform the plot and character development of each of these versions in different ways. The use of foreign languages is also a means by which lovers tell their tales of personal love. In “Les amants shakespeariens Soweto et Gorée, ressusciter Shakespeare avec Sony Labou Tansi”, Alice Desquilbet explores the way Romeo and Juliet, when being transposed to a foreign culture, can be politically challenging. In the Shakespearean tragedy, Misfortune threatens the two lovers and leads them to an unfair death, while the play of Sony Labou Tansi, staged with twenty-four French and Senegalese students on Gorée Island in 2010, offers a reflection on the sacrifice of the two heroes and questions the usefulness of the lovers’ death in an era of ecological waste. As for Marine Deregnoncourt, her Roméo et Juliette is analyzed on the stage of the Comédie-Française, in a production by Éric Ruf in Paris, 2014. She interrogates the genre of the tragedy that seems to have been partly subverted by Ruf’s very singular aesthetic treatment of the tale. The scenography, the music, the historical transposition, and the cast offer an innovative interpretation of the myth and push the boundaries of stagecraft and dramaturgical writing.

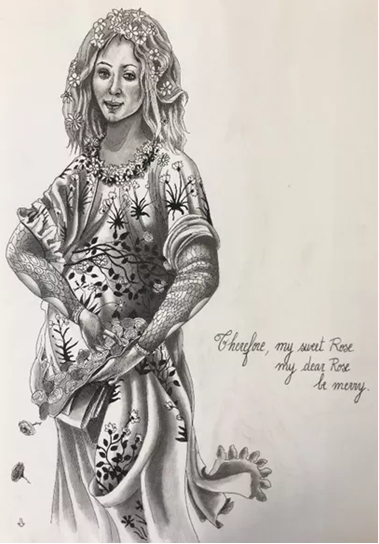

Juliet, ”From Botticelli's Primavera”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

5The second section deals with screen adaptations, the cinematographic art being the other paramount imagistic medium and whose canon is well established with film versions by George Cukor (1936), Franco Zeffirelli (1968), and Baz Luhrmann (1996). Some recent productions have highlighted the ambiguous afterlife of the doomed heroes.1 Aoileann Ni Éigeartaigh, in “‘A glooming peace with it this morning brings’: Struggling against the Tragic Ending of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet”, claims that “Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is in theatrical terms an anomaly” because some of its key features like the melancholic young poet or the dramatic infighting of the families are usually devices intended to lead the lovers to a happy conclusion. However, the deaths of the lovers prevail over the many narratorial opportunities for a comic conclusion that exist within the final Act. Focusing on Zeffirelli, Luhrmann, and Madden (Shakespeare in Love, 1998), this chapter examines the subversion of the tragic ending such that the final Act in these movies becomes “a struggle for dominance between the pre-existing dictates of Shakespeare’s plot” and the audience who expect an overpowering love. Florence Chéron and Kwasu Tembo’s focal reference is also Baz Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, which they respectively present as a postmodern re-imagination and an illustration of a nihilistic love. Florence Chéron first notes that Luhrmann’s work is characterized by a “rare extremism that spares the Shakespearean poetry in a post-modern aesthetics” and seeks to analyse his work through the concept of “re-invention”. In Luhrmann’s film, some words from the original text have been transformed into another form—either visual or sonorous—to underscore all the artistic potentials of the cinema. In the post-apocalyptic set designed by Luhrmann, Chéron analyses how the cinematographic image reflects the chaos of the lovers’ environment. As for Kwasu Tembo, he remarks that most 20th-century adaptations have overlooked Shakespeare's more fundamental exploration of the “radical imbalance produced by love, its catastrophism, and its total cost.” Referring to Derrida and Žižek, among others, the author explains how the Liebestod concept is expressed in Luhrmann’s movie and shows to what extent a will to “Real Love” is also a will to death.

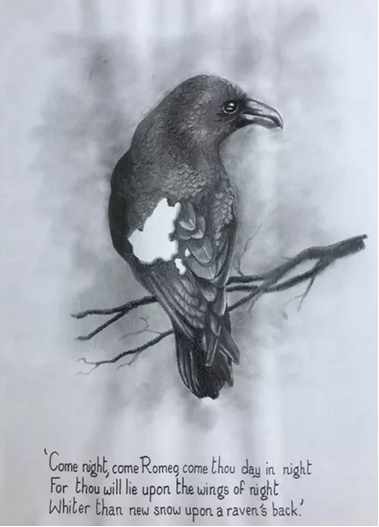

“Romeo and the Crow”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

6The third section includes Jonas Kellermann’s and Laurence Le Diagon-Jacquin’s fascinating analyses on musical compositions. In “Dramaturgies of reciprocity in Romeo and Juliet”, Kellermann refers to Paul A. Kottman’s essay “Defying the Stars: Tragic Love as the Struggle for Freedom in Romeo and Juliet” (2012), to claim the play’s emphasis on mutuality and reciprocity. The latter are dramaturgical factors particularly adaptable beyond the art of spoken drama, such as musical and choreographical adaptations. Kellermann’s paper proposes to read the aubade in III.5 of Shakespeare’s play, the Scène d’amour in Hector Berlioz’s dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette, and Sasha Waltz’s balletic interpretation of the Berlioz piece as a Pas de deux (Paris Opéra Ballet, 2007) to illustrate how a “transverbal” dramaturgical pattern exists beyond Shakespeare’s language. Laurence Le Diagon-Jacquin’s “Roméo et Juliette à l’opéra en France au XIXe siècle : Gounod vs Marquis d’Ivry” takes up the opera Les Amants de Vérone (The Lovers of Verona), composed by Paul de Richard d’Ivry (1829-1903), and Charles Gounod’s own version of Romeo and Juliet in the eponymous opera, presented in the Théâtre lyrique, Paris, in April 27th 1867. Her study explores the crosscurrents of Shakespearean text and musical adaptation in a broader context of nostalgic Romanticism.

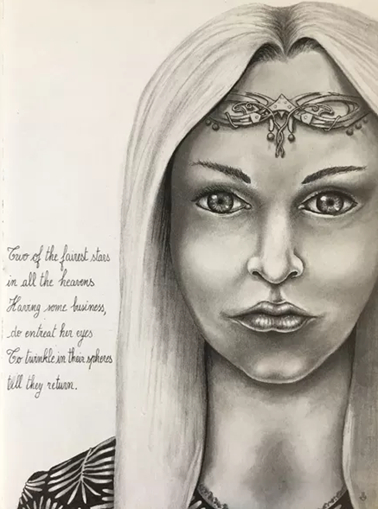

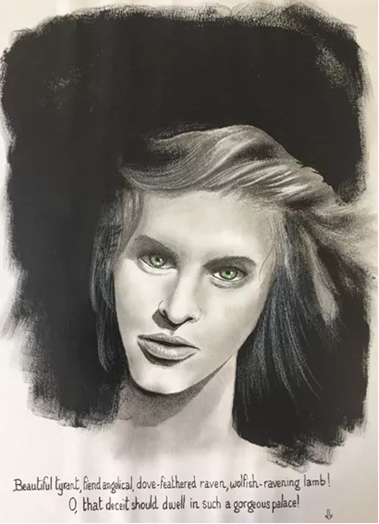

“Juliet’s eyes”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

7The last section of this volume is devoted to the graphic arts and the new media. Brigitte Friant-Kessler’s essay “What if #amazing Romeo heart Juliet LOL?: Shakespeare Emojified and the Challenge of a Funny Tragedy” draws on Henry Jenkins’s concept of “convergence culture”. YOLO Juliet is a graphic and editorial appropriation in which the play is presented in a conversational textspeak style and is based on a “what if” script. The author addresses the effect that “emojification” has when compared to the original play. She simultaneously explores the comical aspect as announced in the publisher’s blurb: “A classic is reborn in this fun and funny adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays!” and wonders how and why a tragedy can become funny. “Beyond the appearance of a repackaged R&J for millennials”, she writes, “the adapted version in emojis as a mode of staging Romeo and Juliet on the page, the use of graphic coding for the dramatic personae and the revisiting of the Shakespearean text as ‘a tiny epic’ cross-bred with a digital tale warrant a thorough exploration. In her paper entitled “Veronaville, exemple d’une adaptation vidéoludique de Shakespeare”, Louise Fang investigates the way the immersive aesthetics of video games contrasts with a theatrical experience that repeatedly draws the audience's attention to the dramatic nature of the performance in which they have a role to play. Her essay examines The Sims 2, a simulation game set in Veronaville that enables players to virtually embody the characters. The heroes of the tale, Romeo and Juliet, but also Titania and Oberon and Caliban, evolve in a world both summoning images of the dramatic experience and departing from it. In “‘What are you doing?’ Reclaiming Juliet’s Agency in the YouTube Series My Sassy Gay Friend”, Marlena Tronicke sheds a light on the YouTube series Sassy Gay Friend. She raises a key question, “how does the series manage to offer a nuanced reading of Juliet’s suicide and its link to female agency?” In both the play and its adaptations, Juliet’s death is presented as the only escape from patriarchal domination (a recurrent motif in Shakespeare’s canon, even in comedies, as the beginning of A Midsummer Night’s Dream). In its re-writing of Juliet’s suicide scene, the Sassy Gay Friend re-claims Juliet’s agency, an agency lost in the cultural myth of tragic inevitability. The essay is also a way to assess how YouTube productions engage a dialogue between script and viewers, thus proving how interactivity around such issues as female agency are jointly forged in contemporary online media. Finally, in “A Story for Children? Illustrer les éditions jeunesse des Amants de Vérone”, Éléonore Cartellier and Estelle Rivier-Arnaud consider the transposition of young love in six illustrated books for children. Three are in English and three in French. They focus on the way these albums and picture-books condense the tale, highlighting or deleting some of its lines, with a view to serving didactic and aesthetical purposes. Some of the most expressive scenes—the balcony, the first kiss, the wedding night, the duels and the suicides—are more precisely examined in order to understand the ways in which a young readership become aware of the dangers of passion. It is also thanks to the new generations that the myth is bound to be updated and kept alive indefinitely.

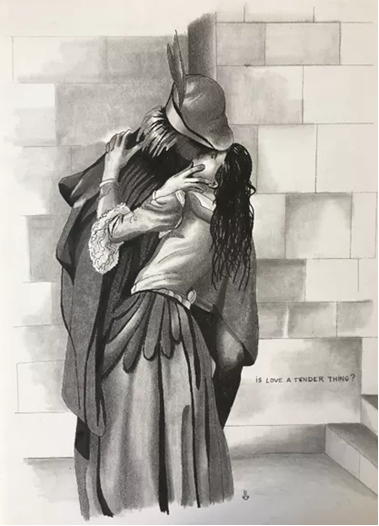

Original sketch inspired from Il Bacio by Francesco Hayez.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

8To conclude the volume, and somehow in the continuity of the last chapter dedicated to picture-books, Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine invites us to journey into the reinvention of another Shakespearean play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in a comic-strip by Raymond Macherot, named Le Sortilège des Gâtines (1968). Isabelle is the heroine of the tale, and she lives at the “Midsummer Inn” (“l’Auberge de la nuit d’été”) where Mr Bottom is the innkeeper. Of course, there are evil characters that Isabelle has to overcome in a series of adventures (among which the influence of a sect) that hint at other references of Shakespearean sources. The author cleverly explores the innuendoes of this entertaining adaptation with wit and apparent jubilation.

Acknowledgement

9On behalf on my two co-editors, Isabelle Schwartz-Gastine and Eric C. Brown, I would like to thank all the authors who have contributed to this volume, and also our family and friends who have helped us keep focused on the project. Let us not forget to thank two students from the University of Grenoble, Alpes—Isabelle Mikovich and Séverine Badin—who have also reviewed some of the articles as part of a training class on the work of edition, and of course Pascale Drouet, the general editor of the Cahiers Shakespeare en devenir, who has kindly welcomed this collection for her annual volume. Finally, as the latter is intended to let the image re-tell the tale, let us leave the concluding words to Jean-Louis Claret’s compositions, exhibited in this introduction, as another way to explain the everlasting contemporaneity of Shakespeare’s play.

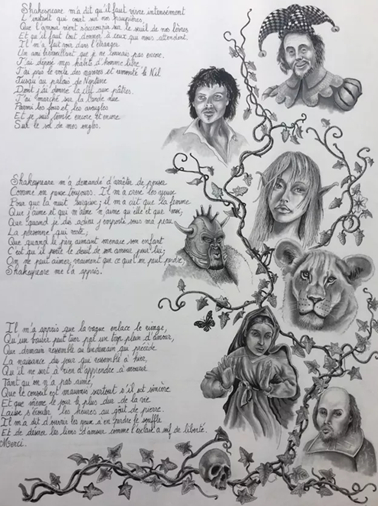

“Poetry and Image”, a text written and illustrated by Jean-Louis Caret.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

“The Lovers”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

“Weeping Flowers”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

“Romeo”.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

Original sketch inspired from L. Signorelli.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

Shakespeare “I am not what I am”, inspired from Parmigianino.

Crédits : Jean-Louis Claret.

Notes

1 See, for instance, Alan Brown’s Private Romeo (2011) set in McKinley Military Academy where the play Romeo and Juliet is being read by the cadets, Tromeo and Juliet (1996), Lloyd Kaufmann’s parody, set in Manhattan, with a pornographic background and heavy gore effects; and Ronnie Khalil’s With a Kiss I die (2018), a vampiric and lesbian re-reading of the lovers’ fate.