- Accueil

- > Shakespeare en devenir

- > N°14 — 2019

- > IV. Arts graphiques et nouveaux media

- > Comicking Romeo and Juliet in the Digital Age, or How to Do Things with Panels and Pixels

Comicking Romeo and Juliet in the Digital Age, or How to Do Things with Panels and Pixels

Par Brigitte Friant-Kessler

Publication en ligne le 19 février 2022

Résumé

The present essay examines how Romeo and Juliet is when adapted as a webcomic and is illustrated with emojis in paper editions that emulate digital conversation platforms. Part of the argument is a larger issue which is the use of stick figures and emojis to represent the characters visually as both have in common the aim to simplify and steer away from realistic figuration while often revealing elements of the “cute” as theorised by Sianne Ngai. Furthermore, webcomics embrace a global and multimodal approach whereby the medium itself allows the artist-illustrator to cross-reference visual adaptations with other discourses. In spite of the apparently reductiveness of emojified pixels and/or digital panels, and the temptation to perceive in those adaptations a degree of decaffeinated Shakespeare, it is argued that the visual rhetoric and performativity which underpin those modes of representation are multifunctional and are thus in keeping with rhizomatic Shakespearean networks as defined by Douglas Lanier. They also gesture in more ways than one toward Shakespeare’s text when it is staged and permanently reappropriated in sight and sound.

Cet article interroge Roméo et Juliette adapté sous forme de strips publiés sur un blog en ligne, ou avec des émojis dans une version imprimée qui simule la communication numérique sur les réseaux sociaux. Il s’intéresse notamment à la façon de représenter visuellement les personnages à l’aide de bonhommes-allumettes ou avec des émojis en postulant que le dénominateur commun est la résistance à une figuration de type réaliste. Ces modes de représentation ne sont pas éloignés de ce que Sianne Ngai a théorisé sous le terme « cute ». D’autre part, les strips en ligne constituent une approche multimodale, globalisante et un moyen de communiquer qui permet à l’artiste-illustratrice de croiser la dimension visuelle avec d’autres formes telles que la musique. Bien qu’à première vue, les strips et les émojis peuvent sembler réducteurs et qu’il est tentant de voir dans ces adaptations du Shakespeare « décafféiné », le propos consiste à démontrer que ces modes graphiques déploient une rhétorique visuelle et une performativité propres qui renvoient à ce que Douglas Lanier a défini comme les réseaux rhizomatiques shakespeariens, en empruntant le concept à Deleuze et Guattari. De fait, les pixels des émojis ainsi que les strips dessinés et diffusés sur la toile offrent l’occasion de repenser le rapport de ces pièces à la mise en scène et à la réappropriation de la dramaturgie constamment renouvelée, en sons et en images.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Comicking Romeo and Juliet in the Digital Age, or How to Do Things with Panels and Pixels (version PDF) (application/pdf – 4,2M)

Texte intégral

1Graphic adaptations come in all shapes and sizes, and we live in what seems to be a golden age for graphic adaptations of mythologised works like Shakespeare’s plays, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, or Jane Austen’s fiction,1 to name but those few. They have all been ceaselessly adapted, illustrated, re-appropriated and remediated so as to circulate among an ever-larger spectrum of readers and on ever expanding platforms. Those adaptations also fit within a broader context of new tastes and trends across genres and styles. One such trend is closely linked to digital publishing on the Internet but equally to adaptations as tools that can convey critical views on the use of digital devices (computers, smartphones, tablets). Creating innovative forms and formats, or imagining graphic designs is a never-ending process mainly conditioned by the search for new marketing segments, for instance, in the bookselling industry, or renewing pedagogical approaches to teaching the classics and incorporate them into what Douglas Lanier coined “Shakespop”.

2Over the last decades, Shakespeare studies have taken on board the impact of popular culture and the permanent morphing of the Bard’s canon into new textual or visual objects that correlate the way technological innovations affect our world in the 21st century. In the wake of the No Fear Shakespeare series, manga-ification, multi-modal animation, comic book repackaging, vlogging, Lego-ing and a wide range of abridged versions, publishers, illustrators and graphic designers have joined forces to promote oddities such as emoji versions of Shakespeare (OMG Shakespeare).2 The cage of Shakespeare’s world has equally been rattled by online ventures like Stick Figure Hamlet discussed in an essay by Pierre Kapitaniak, or Mya Gosling’s graphic blog which is increasingly given attention by academia.3 Originally a library cataloguer who became a full-time comic artist, Mya Gosling revisits the whole Shakespearean canon, which by itself deserves a great deal of admiration. Her blog is particularly captivating both in scope and in choice of graphic expression. As shown by Kapitaniak, Carroll’s Stick Figure Hamlet does contain elements of comedy mingled with the main tragic plotline. Mya Gosling’s webcomic thrives with humour by combining stick figure drawings, vintage photo-novel collages, cameo appearances of herself, multimedia asides, and witty metacomic comments on her graphic endeavours. In many ways Mya Gosling uses the web page like an interactive digital stage onto which her stick figured characters perform week after week scenes set and retold in three-panel strips but which never leave the viewer and Internet-user out of the game.4

3This particular convergence of didactic and graphic dynamics contributes to making the reading of the Bard’s plays online a very entertaining and idiosyncratic experience, from which humour is never absent. Neither is the contemporary language. Compared to Dan Carroll, for instance, who follows the Folger Folio edition to fill bubbles of his webcomic, Gosling engages in retelling the plots of the plays in modern terms, much in the vein of the No Fear Shakespeare approach.5 Her comic strips thus become a graphic venture with parodic components that gesture towards a process I have termed “comicking the canon”. I define comicking as “the process whereby a canonical text or classic literary work is graphically reworked in a comic or cartoon format, and which presents a variable degree of comedy”.

4The common denominator shared by Mya Gosling’s and Dan Carroll’s graphic adaptations is that they do not only illustrate and graphically represent emblematic characters or scenes, or sometimes even entire plays, they also epitomise a current tendency towards something which could be described as the urge for non-tragic tragedies. Dan Carroll’s remark on his blog is in that sense quite illuminating “It was a dopey little drawing, but I just liked how it looked... and decided that Stick Figure Shakespeare would be a hilariously insane project”. The major difference between the two stick figure versions nonetheless is that Mya Gosling’s webcomics and retelling of the plays are part of a constructed, humorous visual Shakespeareana, which actually functions like a globalised digital Goslingeana dedicated to Shakespeare. On the same web site, next to her reduced Shakespeare play panels, we discover, for instance, her passion for rock climbing.

5I will examine Gosling’s Good Tickle Brain blog by focusing on her Romeo and Juliet webcomic series and comics that are not immediately connected to the play but function as spin-offs when mixed with other topics. I will compare her webcomics to specific aspects of YOLO Juliet an edition6 of Romeo and Juliet which presents another kind of intermedial adaptation yet shares with the webcomic the notion of performativeness.7

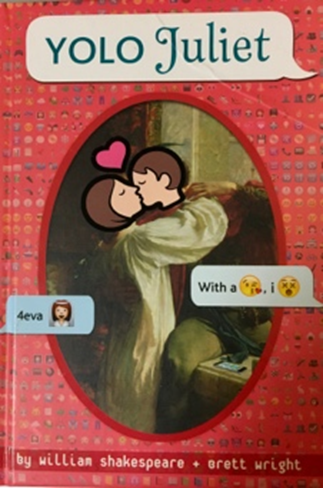

YOLO Juliet, book cover

Crédits : Random House, New York, 2015

6While both were created in the age of digital communication, Gosling’s adaptation of the play, as well as separate scenes which she revisits, signpost a critical discourse on our all-digital age which YOLO does, but to a lesser degree. Stick figures, emojis, or indeed every day objects as in Table Top Shakespeare shows, for instance, relate to anthropomorphised representations which can result in something that is non-tragic tragedy because of the way the plot and the text are mediated, and, to borrow from Bolter and Grusin, also remediated. But like Table Top Shakespeare performances that retell the plays Gosling’s strips are “bite-sized and easy to digest”.8 However, I would like to argue that cuteness which is at the core of most of the above mentioned adaptations involves suspension of disbelief and more so in the YOLO Juliet version. The performative powerlessness of the plot of Romeo and Juliet is thus made to revolve around unthreatening situations, which are also destined to become attractive to a new host of readers.

Comicking Romeo and Juliet and Spreading “the Cute”

7Webcomics are part of modern spreadable media.9 Geoffrey Long notes that it allows “to spread online content to huge audiences”, in other words, it becomes a formidable means of revivifying and disseminating classic literature too. In a section devoted to re-inventing Comics, comic theorist and author Scott McCloud underlines that as early as the beginning of the new millenium online distribution heralded major changes in comic publishing and reading practices. McCloud’s manifesto for new formats and modes of comic publishing anticipated how webcomics would open unexpected vistas for independent artists, fans and readers alike as it “positioned the web as more open space for newcomers.”10 Web comics are also one of the manifestations of what Henry Jenkins defined in Textual Poachers as follows: “Fandom here becomes a participatory culture which transforms the experience of medai consumption into the production of new texts, indeed of a new culture and a new community.”11 Mya Gosling’s Good Tickle Brain blog, with a name in itself aimed at Shakespeare afficionados, encourages audience and readership to get actively involved, part of which has resulted in a successful commercial operation by Mya Gosling who migrated some of her works on Patreon.12

8Creating a serialised webcomic means having an invisible fandom in mind and regularly posting or updating the blog for an active one. If not engaged in the reading and the commenting of the comic, some fans may contribute as lurkers i.e. people who read online comments but do not post any.13 Mya Gosling’s mode of addressing indirectly and directly her readership offers something for active readers and lurkers alike. Compared to a live audience in a playhouse, lurkers would be those who enjoy watching a play on stage without manifesting any particular sign of affective involvement, while the other clap and cheer out loud their enjoyment of the performance. Kevin Wetmore argues that comics and staged performances have a lot in common. Webcomics even more so since they afford an interactive space of exchanges between readers and the artist that paper editions cannnot. They are serialised like the older traditional magazine formats (Classics Illustrated from the 1940s onwards) but their access is free which again bridges another gap in readership renewal.

9In addition to the spreadability and the appealing digital format, Mya Gosling’s blog revisits the plays, and Romeo and Juliet in particular so as to minimise, if not completely remove, the burning sting of tragedy in it. The fate of the star-crossed lovers is continously interspersed with amusing asides on the cartoonist’s part. Mya Gosling explains in an interview conducted by Ann Arbor Librarian Christopher Porter that her passion for Shakespeare is first and foremost grounded in her going to the playhouse with her parents. Plays are thus conceived of as shows to be seen on stage, whether materialised in wood or on the web. The stick figure as a graphic mode also reunites adaptation and what Sianne Ngai has theorised as an aesthetic category: the “cute”. Several questions arise from the link thus established between such graphic adaptations and cuteness culture. What has cuteness done to Shakespeare’s emblematic ill-fated couple? And how is this cuteness visually distilled in recent Romeo and Juliet adaptations? As for the why of this trend in adaptations, it stands to reason to agree with Sianne Ngai and Perish when they argue that there has been an onslaught of cuteness in the course of the two last decades. From Japanese kawaii, to Disneyification and cute cat memes, the craving for cuteness seems to be everywhere, even where least expected. Without necessarily embracing the parodic though, cute tragedy suggests a hybridisation of the canonical genre, a process in which stick figures may play a significant role, as do emojis.

10What Sianne Ngai and Lori Merish have theorised as “commodity cuteness” percolates through adaptations and a certain type of re-telling, especially when the latter is also imbued with a didactic or ludic touch. For the didactic touch, there are numerous webcomic versions of Romeo and Juliet that rely on comic format. For instance, David Rickert’s web pages and the pedagogical activity bundles on the aptly named site “Teacherspayteachers” adapt the play too.14 The combination of revisited tragedy for teaching purposes showcases simplification both in word and image. The premise being that Shakespeare’s English has become inaccessible, adaptations rework the text but also frequently reformulate the plot so as to further reduce comprehension obstacles. That such retellings can lead to amusing situations is not incompatible with the re-appropriation of the play. Bearing in mind the pedagogical effort, Classics Illustrated in comic format typically fall into the category of “comicking” but those adaptations far from turning tragedy into comedy actually reinforce it by creating a visual dramatisation of the scenes. Designed for a young readership, often not familiar with the canon, whether Shakespearean or other, they fill the gap between school curricula Shakespeare and on-stage performances of the original text. Taking the comparison of stage and comic page as a starting point, a number of parallels can thus be drawn between reading the text on the page, watching the play on stage and accessing both on screens, be it silver screen, small screen or indeed computer screens.

11Incidentally silver screen adaptations, mostly Zeffirelli’s, frequently serve as springboard for parodic intermedial and transmedial adaptations. A case in point on May Gosling’s blog is the post related to her visiting the Stratford festival in which she transposes pictures of Romeo and Juliet.

Photo comic of Stratford festival 2017

Crédits : Good Tickle Brain

12The stage is made of photo-novelised panels which aim to update and adapt the first dialogue scene between Romeo and Juliet at the ball.15 Emblematic Italian Renaissance period costumes are mashed-up with “cute and smooch” and feud-laden insults in the speech bubbles. One panel stands out as it features a weird character that launches into a somewhat Monty Pythonesque blackmailing address by saying “Either you come to the party with me, or I’m going to make up a long rambling speech about fairies”. Chances are that the term “fairies” was chosen here for its preposterousness in the context as well as its polysemous signifier for a non-earthly creature? The double-entendre in the slang word for homosexual — in this case not used to offend — becomes a humorous way to tangentially remind web readers, or possibly even only alert them to, the fact that female roles were acted out by men in Elizabethan theatre. But the characteristic feature of May Gosling’s visual adaptations are not photos but her signature three-panel comics with stick figure characters.

How to Do Things with Stick Figures and Emojis

13Shakespeare’s plays are constantly made more transmedial, more palatable, and as advertised on the back cover of YOLO Juliet, a “whole lot more interesting”, which strangely seems to imply that prior to being read in this new format it must have been dull and boring. Clearly the pitch of such blurbs is to attract Young Adult readers as well as to give the plays a ludic yet equally strongly pedagogical dimension. Published in 2015 by Random House (New York), the small hardback volume (a mere A5) intriguingly boasts a collaborative work by a revivified William Shakespeare from another age and one Brett Wright, the illustrator, connected to the modern world. Brett Wright’s short biographical notice at the end mentions that “in college he studied Shakespearian tragedy, which was sadly lacking in emoticons”. The additiontal remark, almost like a quip, seems rhetorically designed to elicit a smile on the reader in the know’s face, and a sense of complicity in those who feel closer to students that did not develop a particular keenness for Shakespeare. The scene is thus set for the reader to expect something exciting, different because digital-related and undoubtedly entertaining, all of which posits a counterpoint to the mental representation of what Shakespeare’s tragedy would otherwise have been, or indeed how they were implanted in the brain by the school system. In her foray into “the interesting” as an aesthetic category, Sianne Ngai argues that “any aesthetic category is fundamentally related to intersubjective and affective dynamics”16 and that “an object can never be interesting in and of itself, but only when checked against another: the thing against its description, the individual object against its generic type. This makes the interesting both a curiously balanced and a curiously unstable aesthetic experience”.17 To follow Sianne Ngai, one might apply this view to the graphically emojified version by pointing out that the experience of reading YOLO Juliet is both unsettling because of the format and what it purports to achieve yet closer in form to performing the text on stage with separate cues or stage instructions than a standard illustrated edition.

14What’s in an emoji? Popularised over the last two decades which have witnessed a spectacular acceleration in communication technologies emojis have become a daily staple, together with textspeak. In 2015, the Word of the Year at Oxford Dictionaries was “emoji”.18 Brett Wright refers to emoticons in his blurb, probably in a generic sense but he should actually have used the term “emojis”.19 Thus the miniature portraits that illustrate the dramatis personae page at the beginning of the book are actually reproductions of 12x12 pixel images and are technically to be referred to as print reproductions of emojis which follow the Unicode standard.

YOLO Juliet, dramatis personae

Crédits : Random House, New York, 2015

15Fan fiction and fan art have soared over the same period of time and have gradually attracted attention in academia, as demonstrated by Henry Jenkins’ Textual Poachers. The momentum to see the world of popular classics converge in order to appeal to a younger, presumably an adolescent audience, with the world of contemporary communication via mobile is nowhere so obvious as when publishers offer hybrid objects such as the 2015 emojified versions of four of Shakespeare’s plays. Among this quartet is YOLO Juliet that I propose to analyse in relation with digital media and generation Z readers.20 The same year YOLO Juliet was published Jamie Rector, a Manchester-based design student, turned Shakespeare’s plays into emojis too, pushing the boundary even further by not only eliminating the simulated conversations but by gathering all the characters on a single sheet.21 The play thus becomes a sequence of hieroglyphic signs similar to a coded chart. Such a paratactical layout means that the interactions and the logical sequence of events are entirely left for the reader to decipher. In her own words, her objective was “to rebrand” Shakespeare. The final result was the covers of her books displayed in a gallery. By steering fully away from verbal references Jamie Rector’s layouts and graphic adaptation becomes akin to an abstract work in the form of a partly conceptual print design.

16Henry Jenkins’s concept of ‘convergence culture’ applies to a situation where the digital world collides with more traditional cultural objects, i.e. books. YOLO Juliet is a graphic and editorial appropriation in which the play is presented in a conversational textspeak style and is based on a “what if” script. The reader’s horizon of expectation in that “What if” script is twofold: what if the two lovers had been the fortunate owners of modern mobile devices? In this particular case, not just any cell phone but clearly an Iphone since the emojis used are recognisable as the Unicode symbols of the Apple Company. In addition, the “what if” mode, like fan fiction writers interacting online, is meant to generate a story line that can sometimes be identified as an alternative plot, if not entirely divergent from the original one, at least it stands for a means to engage with the script. It can fill elliptic gaps, divert the plot from its original route, add characters, or stubstantially modify the outcome. Moreover, emojification can induce changes in performing the scenes. It does not simply make a canonical text from the Renaissance look more contemporary, but, as signified by several Youtube posts, that particular version has actually prompted people to read it aloud in front of the camera and clearly struggle with the symbols.22 In other words, the emojified text has led to performing the play on private, multimodal platforms, or rather digital stages, which spread, can be shared and accessed worldwide.

17Ironically though the very act of reading emojis aloud is bound to fail as those signs require more words to be explained.

18The pervasiveness of the “What if” mode is also significant in May Gosling’s work though with a self-deriding angle that gestures towards a metacomicality which is less present in the YOLO Juliet adaptation. Glenn Fuller proposes an analysis of the term ‘meta’ in an essay on television assemblage.23 If we apply his concept to Mya Gosling’s web comic we can argue that it is ‘meta’ in the way fan and mass audiences can be encouraged to develop an intertextual meta-Shakespearean media literacy. Mya Gosling overtly explains she wants to revamp the Shakespearean canon by drawing three-panel strips in which the scenes and the characters quip jokes to one another. The format itself is based on that of a joke: beginning, middle and punch line ending. She also indulges in what I call “adaptshrinking” the plot: each play is reduced to such a minimal statement so that it is still recognisable yet entirely revisited in spirit. She ascribes the Elizabethan plays a contemporary flare that is not only amusing but mildly satirical while the parodic dimension of her work brazenly relies on globalised participatory consumption, commentaries posted by fans and internet users. To follow Glenn Fuller further “[c]ontemporary popular culture is an effect of the globalisation of the creative industries and the ongoing territorialisation of everyday life by mass-media spectacles intensified through personalised vectoral modes of delivery”.24

19Initially aimed at readers who are also allegedly heavy television series consumers, hence the very American OMG (Oh My God!) Shakespeare choice for the collection, Youtube live performing of the YOLO Juliet is done by adults who describe themselves as Shakespeare fans. For all these reasons the graphic adaptation goes hand in hand with visual and vocal spin-offs. Most of the digital exchanges in the YOLO Juliet strive to restore the plot, in spite of its minimal style. The act of reading aloud, however, although potentially executed so as to reminisce stage acting, makes the version close to incomprehensible: it is permanently interlarded with read aloud emojis and hashtags, all of which are codes that are designed to remain visual and not voiced. Such an effect can become a stumble block, for instance when readers attempt to deliver orally a text with hieroglyphic objects, or typographic games (asterisks, dashes, squiggly lines) as in the eccentric page layout of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, the epitome of the moment in the cultural history of European literature when orality became subsumed in written culture according, for instance, to critics like Alexis Tadié.25

20For all its efforts to look digital, the effect of printed emojification simulates a digital world on paper and therefore appears to nullify the performative power of this type of exchanges. Furthermore, by mixing oral, graphic and digital modes of communication, the success and the efficiency remain limited precisely because of a transmedial coding and the graphically transmogrified text, which is different from other visual adaptations. While the publisher’s blurb reads: “[a] classic is reborn in this fun and funny adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays!” one wonders how and why a tragedy can or indeed should become funny. Is there something prescriptive about the tragic ending of this play? What are we supposed to make of advertising tags like: “This hilarious boxed set includes adaptations of Shakespeare's most beloved tragedies”? Since the overall approach of emojification follows the one adopted in short format graphic adaptations that rely on stylisation, lack of realistic details and reduction, one can draw parallels with humorous adaptations in short formats such as comic strips, caricature or webcomics. But emojis are a code-built repertoire of facial expressions and/or pictographic representations of people and, rather like hieroglyphic charts, they are inherently unable to do what language, and even more so, what poetry does. Charles LeBrun’s treaty to chart passions and emotions [Les Expressions des passions de l’âme, 1727] comes here to mind, but unlike Charles LeBrun whose aim was to provide in the first place artists with a set of templates, emojis are intersubjective and intend to help other people visualise one’s own reactions and emotional mindset. In the process, the emotional impact which is codified bars the reader from unexpected and spontaneous responses, or, at times, which is even more problematic, makes access to the meaning look like a hurdle, even for Generation Y readers.

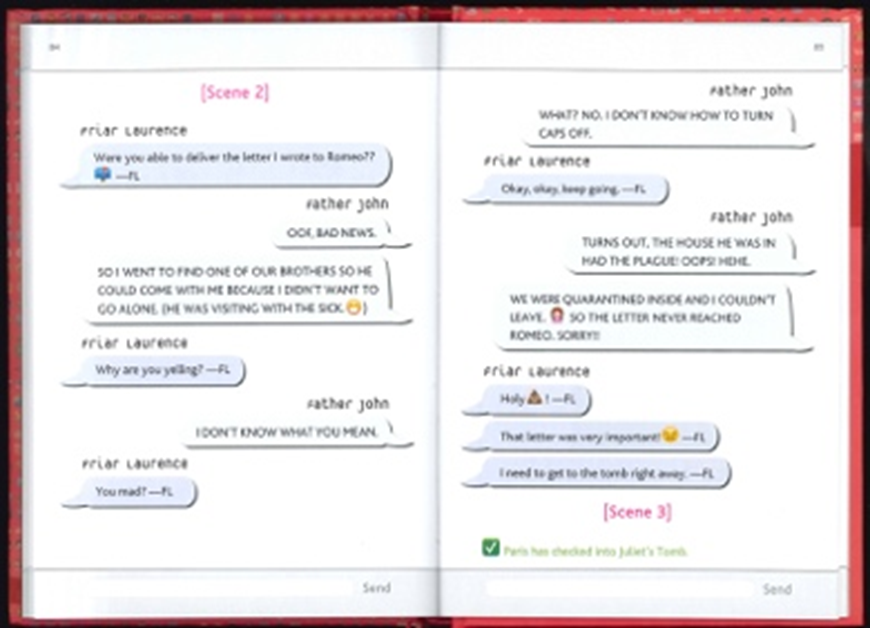

21Because emojis are designed to elicit emotional responses by adding a set of visual cues to the text, they are also meant to recreate corporeal expressions that are by essence absent from distant exchanges, except nowadays in video communication. In the context of OMG Shakespeare, however, emojis fail to compensate for the distance in more ways than one. In fact, a surfeit of contradictory signals and graphic encoding becomes counter-productive. In spite of an appealing cover blurb and laudatory online comments such as “a snap and a snazz”, one quickly realises that the reading-cum-t(e)xting system is seriously challenging and this prompts us to question both the fun and the pleasure readers can derive from this kind of “adaptexting”, regardless of their age unless one goes for critical interpretation of the inadequacy of communication in using emojis like that. Two examples in YOLO Juliet spring to mind: one is a reference to autocorrect mistakes in digital communication and the other is a mildly amusing criticism of Friar John who proves inept at using textspeak etiquette and can’t turn off the caps on this keyboard

YOLO Juliet, Friar John’s use of textspeak

Crédits : Random House, New York, 2015

22However, beyond the appearance of a repackaged Romeo and Juliet for millennials, the side glance to popular culture such as Taylor Swift’s Romeo and Juliet-inspired 2009 song Love Story and listened to on one aptly named Renaissance FM, the adapted version in emojis as a mode of staging Romeo and Juliet on the page, the use of graphic coding for the dramatic personae and the revisiting of the Shakespearean text as a tiny epic cross-bred with a digital tale do not appear to fully hit the mark. Nor does an inserted photo of the original balcony in Verona (p. 21) entirely create the cross-over effect it would have if the text were actually online.

23Mya Gosling has embarked on a very challenging task too which is comicking and stick-figuring at once. The result is an impressive graphic oeuvre informed by her close reading of the plays and her unbinding love for the playwright, as she recurrently likes to assert. From musical-inspired strips (Hamilton, The Pirates of Penzance) to revisited Christmas carols, her range of transmedial adaptations and references seems almost endless.26 Mya Gosling’s strips illustrate and simultaneously comment on how twenty-first-century readers can engage with the original text. Regarding young readers she simultaneously wishes to trigger a desire for more original Shakespeare, preferably on stage, yet readers who have a degree of expertise will find the material delightful because it is frequently parodied. By playing with theatrical genres and subverting their axiology, her graphic humour endeavours to point out limits and constraints, as stated, for instance, on the web page entitled “A Modern Major Shakespeare Fan.”27.This parodic layer cake of Shakespeare-based mini-comics adapted to be sung to the tune of Gilbert & Sullivan’s classic Major-General patter song from The Pirates of Penzance makes for a savoury postmodern bricolage. In spite of a seemingly childish stick-figure drawing Mya Gosling’s adaptshrinking of Shakespearean tragedies, in particular Romeo and Juliet, channels a whole set of references ranging from classic literature to Victorian comic opera28 and many more visual side-dishes. The latter contribute to deflecting the tragic mode and turn even the grimmest scenes into comedic pieces. Contrary to Brett Wright, Mya Gosling underscores on her webpage she was literally cradled in Bardish plays and has, ever since she was a child, had a strong liking for the original plays. Her webcomics are short but significant tributes to the whole canon.29 The metaphor she uses to describe her connection to the Shakespearean canon is that of an “endless sandbox created by the playwright for us and artists to play in”30 across time periods, genres and styles. One of those games is self-reflexive webology, or in other words what happens when the web and (web)comics take a self-deriding and critical look at digital culture from which they spring.

Small Digital Comedies of Errors: Romeo and Juliet and the Cupertino Effect

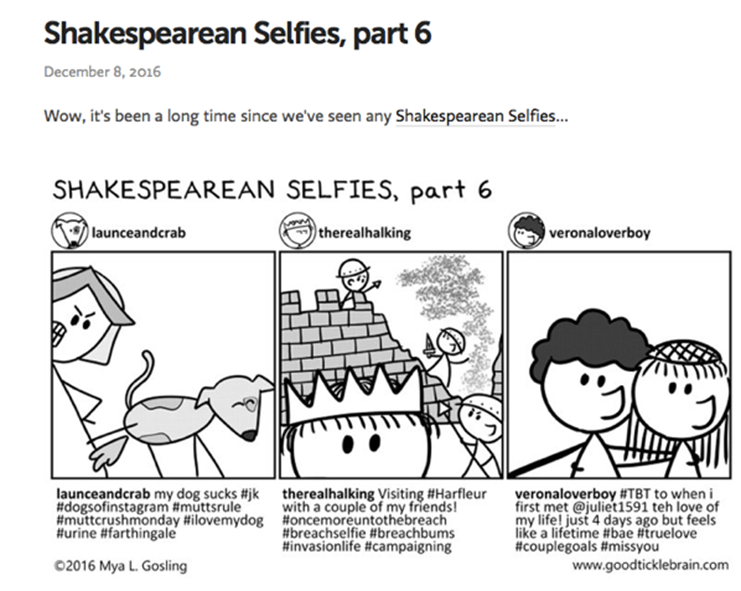

24Examples of humorous takes on Romeo and Juliet abound, particularly in cartoons. Dan Carroll’s Stick Figure Hamlet has also cartoony elements as noted by Pierre Kapitaniak but Mya Gosling’s webcomic is imbued with a satirical turn when she uses the play to point to the flaws (and limits) of our digital societies. Global questions arise from some panels such as how far we should let machines write for us or not. A series of strips on the blog address autocorrect typing, selfies or other digital modes of communication which prominently feature either Romeo, Juliet or both, and offer reflections on how young adults and teens communicate and how they use mobile devices.31

Romeo and Juliet as part of Shakespearean selfies series

Crédits : Good Tickle Brain

25As readers and digital device users we have all experienced writing / receiving nonsensical text just because the in-built autocorrect function activated its passive-aggressive retyping of the word. If not entirely catachrestic, what was initially planned still feels like a digital version of spoonerism. Roz Chast drew a famous Shakespearean cartoon for the New Yorker in 2002 in which two teenagers incarnate a revisited Romeo and Juliet situation which Marjorie Garber describes as “consciously bathetic”. One of the pair is grounded and their digital conversation revolves around bad marks at school and subjects that “suck”. The language is a combination of textspeak abbreviations (u, wassup, gtg, 2day) and low-register expressions (scool sucked, what a jerk, lack of grammatical ‘s’).32 The delayed parting reminisces the emblematic balcony scene. YOLO Juliet transposes the balcony scene for textspeak with an introductory “Romeo checked into the Ground Below Juliet’s Balcon”. May Gosling also created panels for the balcony scene but added an extra-layer of delaying by announcing it weeks before. Blogging being by essence a serialised way to publish it allowed her to generate a teaser paradoxically based on something everybody knows. By repeating “it’s coming”, blog readers simultaneously knew what to expect yet were also made aware they were going to be treated with a surprise.

26Sigmund Freud and Henri Bergson theorised humour and both concurr to say it stems from surprise. Autocorrect functions on our mobiles, or rather dysfunctions, can produce spectacular astonishment, or sometimes major bones of contention due to the misunderstandings. As such “autocorrect” is also a very efficient trope in cartooning to mock the limits of digital conversation, it can sometimes verge on very poetic gibberish.33 When applied to Romeo and Juliet the tragedy, the situation depicted in the play can be interpreted as the story of one gigantic Cupertino Effect, the name given to this kind of errors produced by the machine. Autocorrect relates to unfortunate misinterpretation or missed opportunities to get it right, much in the way Friar John could not get crucial information to Romeo on time. In other words, the glitch proved fatal.

27Mya Gosling underlines Act V, scene 2, a particularly tragic moment of the play, by inserting a footnote “You had ONE JOB, Friar Laurence, and you screwed it up. ONE JOB”.34 Like a Greek chorus standing on the side of the stage, she voices frustration and despair caused by the unfortunate event. The magnified type font in bold is a means of sharing her emotional state with the community who is expected to chime in and see eye to eye with her views. As a mimicry of loud shouting, large type stands for graphic orality in comics in general but in digital mod it is interpreted as being rude, which is why in YOLO Juliet Friar Laurence reacts to Friar John’s excessive use of capitals. While initially designed to make us smile and afford a moment of entertainment, the autocorrect series on Mya Gosling’s blog becomes a sub-series in its own right, as well as a visual epitome for communication mishaps which in turn are a reminder of the unfortunate fate that befell the young lovers in the play. This is not to say that all autocorrect mistakes have tragic consequences, but the revolving emotion induced by the anachronistic use of digital communication strangely superimposes its dire conclusiveness onto the veil of comedy. Emoji charts function as short-cuts and are by essence semaphoric but they are also paradoxically saturated with emotional signs linked to digital conversing so predominant in cuteness culture. However, without any prior knowledge of the play the paratactic mode of such emoji charts pushes the limits of comprehension. Rather like logotypes, the characters remain generic as do the actions and the props. Regarding adaptation, Raymond Queneau’s Exercices de style or Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story come to mind when we see diagrammatic charts, comics. Even Table Top Shakespeare’s tour de force of reducing the Bard’s whole canon to a few kitchen utensils and domestic objects forces us to concentrate on the narrativity of the plot as the centre piece of the plays.

28On a page entitled “Wherefore and Why” posted by Mya Gosling her stick figures suggest more than adapting and comicking the play. They offer a critical take on linguistic stumble blocks and the panels refract the canonical text by recasting arguments about what Shakespeare’s word mean, meant and can still convey or not. The page on the “Avenge / Revenge” controversy deftly fits several bills. In addition, it provides digital readers with a useful footnote on Elizabethan linguistic forms.35 Mya Gosling also makes a point regarding remarks allegedly posted to redress a mistake but which incidentally – and probably not only with erudition in mind – put the illustrator in an underling position of someone who dabbles in image but not in text. While other self-reflective pages are included on the blog, this one shows that Mya Gosling knows her Shakespeare, and she does in more ways than one. In spite of what looks like a child-drawn simplified graphic style, keen theatregoer and Stratford-festival-attendant Mya Gosling manages to argue her case as a Shakespeare fan with panache.

Panels and Pixels: Is Visual Brevity the Soul of Adaptation?

29Ever since Douglas Lanier’s seminal study of Shakespeare in popular culture, we have acutely become aware of new modes of circulation of Shakespeare’s plays. That cuteness has increasingly become an important element of the cultural and artistic agenda needs to be taken into consideration, as does the gradual omnipresence of fandom and convergence culture via social networks, digital platforms and new graphic genres. Webcomics not only strive to strike a balance between panels and pixels, they also show new ways of navigating globalised communication in an environment where all the web is a stage. Romeo and Juliet adaptations in three-panel strips and webcomics are predominantly a story-telling mode, particularly when executed in stick figures. If we remove the text, the stick figures clearly struggle to convey the narrative on their own, contrary to what occurs in the classics illustrated comics, or the Manga Shakespeare edition of Romeo and Juliet which capitalises on the Japanification of the plot and the setting to underscore its dramatic effects which shows that comic adaptations do not automatically result in a comical and amusing material. Webcomics tell us as much about the original that has become an all encompassing and ubiquitous trope for unhappy and doomed love as about our contemporary and heavily digitised way of life in which we constantly oscillate between creative explorations and classical roots, as well as between collective participatory fandom culture and graphic remaking of fragments. While Dan Carroll plays with the digital page layout and recasts an unabridged text for speech bubbles the visual landscape drawn by Mya Gosling’s Shakespeareana and Romeo and Juliet in particular is one that derives from the spreadability of webcomics. They attract newcomers because of the networked culture they are connected to and simultaneously manage to increase the stickiness factor which signals the viability of the blog, or the platform. In spite of the medium’s brevity, the Bard’s presence in such media can only testify once and again of a sound longevity.

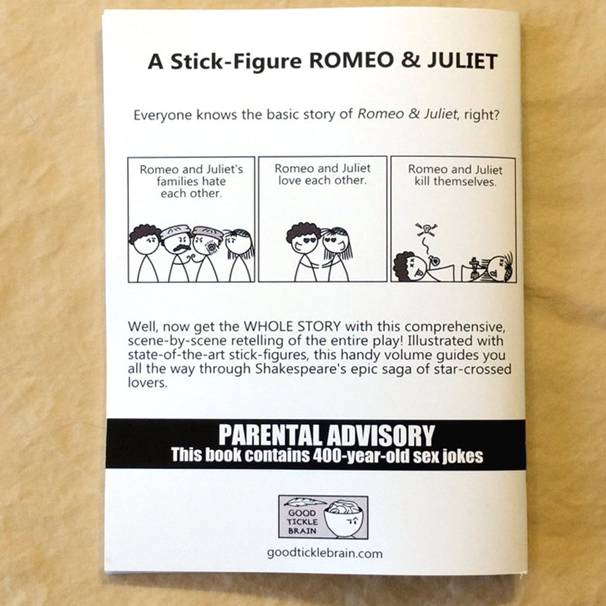

30Mya Gosling’s comics are not just short graphic adaptations, but the strips form a multimedia serialised Romeo and Juliet performed online and reinforced by digital tagging (musicals, character iconography, a making of for the Patreon crowdfunding platform). Each character for each play has its own iconography chart.36

Juliet iconography

Crédits : Good Tickle Brain

31Always bearing in mind the reader’s entertainment satisfaction Mya Gosling puts links that cross-reference all the plays. We can even practice Shakespeare stick figure drawing in a DIY style, and the blog strips have even morphed into a printed booklet

Romeo and Juliet booklet, back cover

Crédits : Good Tickle Brain

32Often submitted to the constraints of simplified retelling, there is a subtext in those panels that allows the media to become the vehicle for a cultural and aesthetic critique. In spite of their apparent simplicity and straight-forwardness, these webcomics, which can also lead to paper versions (Mya Gosling, Ryan North, Dan Carroll), reflect on the limits of today’s passive-aggressive communication styles, as exemplified in the “Avenge/Revenge” example. The urge for hyperbolised affectiveness seems then to function as an almost logical counterpoint. For all the bloodshed drawn in bright splashes of red, daggers get a rhetorical pink coating. Rather like an extra-layer of varnish which is designed to conceal its intially lethal quality, digital treatment, inadvertently or not, suggests a deliberate blunting of the weapons.

33By emojifying Romeo and Juliet, there is an analogous attempt at creating what might be termed a somewhat decaffeinated tragedy, or rather a newly flavoured one. The 12x12 pixel images are visually reductive and the resulting short-cut can also abridge, if not annhilate a sense of despair. Emojis remove the painful sting of fatal errors which lead to a series of tragic deaths, typically the use of digital coding at the end of the book when lady Capulet posts a like-thumb-up on hearing the crowd has gathered at the funeral of the couple which incidentally is reunited “for eternity” across the ether. Emojis appear to pitch a narrative in which glowing hearts and wide smiles on recognisable and interchangeable yellow circles contribute to reinforcing the longing created by a desire to go bland. One wonders if such short-cuts are signifiers of new resilience regimes as well as indicators for a growing need to de-textify. The more images there are, the blinder we are made to feel when confronted with the un-cute and the tragic. Yet, to borrow from Macbeth’s famous line, for all the stick figures, parodies and fun, the underlying violence embedded in tragedy made to mirror real life will never simply melt “as breath into the wind”.37

34Significant shifts in adaptation and visual rendering of archetypal scenes such as Ryan North’s Romeo and/or Juliet edition show that the tendency to steer away from the inevitable sad ending looms large.38 From the onset that play was a formidable “what if” plot and one can hardly imagine early modern audiences not feeling pangs of anguish at that thought. A different “what if”-based scenario is that of North’s game of mathematical probabilities which replaces the acceptance of what or who was previously doomed to suffer, feel hurt, mentally tormented, betrayed, or succumb in bitter qualms of madness. The diversity in the illustrations that come with Ryan North’s book itself reminiscent of the 1980s vogue of books in which you were the hero is indicative of the multiple paths one can embark on when deciding what image best goes with what scene while the multiplication of possible graphic styles opens yet more avenues. From the cartoonesque parody to the sober and allegedly more traditional visual rendering, the spectrum seems almost endless, and it probably is.

35At one point, Mya Gosling adds a comment on stick figures that do not work well for meta-theatricality.39 I would beg to differ and argue they can prove adaptable for meta-Shakespearean comments on top of adapting, and indeed adaptshrinking the text. The latter frequently prevails over image in her approach to comicking Shakespeare. As a spin-off the example of the “Wherefore and Why” page works like a visual afterthought, with an additional stickler’s footnote. From a formal viewpoint it bridges the gap between webcomic format adaptation with stick figure and meta-linguistic coda. Based on the emblematic and archetypal balcony scene from which a burlesque argument arises between the lovers, the page also fulfils its role as a platform for contemporary arguments on non-Shakespearean topics. In that respect, Gnomeo and Juliet [Kelly Asbury, 2011] springs to mind too.

36But the additional scope given to the webcomic allows Mya Gosling to cast an even wider adaptative net, precisely by dwelling on an archaic and therefore currently incomprehensible linguistic form. Like the autocorrect pages derived from comicking the rest of the plays, which includes Rome and Juliet, she creates a mini comedy of manners which, in spite of its marginality, captures the essence of what is left of Shakespeare, at least in most people’s mindset. Romeo and Juliet is more of a reference point in this case and less the material she illustrates. In that respect, YOLO Juliet, Good Tickle Brain and to some extent Table Top Shakespeare retelling by Forced Entertainmen converge. The argument stands inasmuch as the play triggered the debate and Mya Gosling responds by doing what she purports to do all along: dramatising speech with panels and act out her role as visual stage director. The limits of her staging though are inherent to the choice of graphic style: absence of background sets, no props and no colours.

37Good Tickle Brain readers are familiar with the praxis of hyper reading, the convention of her panels. Rather than Shakespeare readers they are, in the sense given by Valerie Fazel and Louise Geddes Shakespeare users. “Instead of building a bridge between the Elizabethan past and our present, this new model of cultural materialism recognizes a palimpsest that does not only move vertically, placing the present on top of the past, but also branches out geographically, technologically, cross-culturally”.40 According to Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn, as with genres, “adaptations set up audience expectations”41 but being a (blog) user generates a different experience: humour adds yet another layer to that experience. Douglas Lanier proposes a model for Shakespearean criticism by adapting Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of rhizome. In such a rhizomatic Shakespeare environment comicking a tragedy equates with the non resolution sought by a model “which is a continuous, self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination or external end”.42 A similar approach can be traced when Mya Gosling comments on the tragedy comedy divide and her plans to adapt A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “while it's comparatively easy to make tragedies hilarious, it’s hard to make a good comedy funnier than it already is”.43 The tragic begs to be turned on its head to become hilarious, yet tragedy would appear to be a more malleable material for such a reversal. While YOLO Juliet is more akin to a skeuomorphic remediation of digital communication, the permanent play on the high-low genres in this LO-FI format, the bathos and theatricality in Mya Gosling’s panels showcase how to do things with comics in a different mode, in a more rhizomatic vein. Instead of redecorating the graphic and digital stage44, Gosling literally strips it down to its most minimal style and form. Stick figures as a graphic style tend to be largely underrated mostly because it is reminiscent of children’s limited drawing skills but by opting for such a style, she takes Romeo and Juliet, together with the whole canon through stick and fun. To quote Douglas Lanier again when he models his argument on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: “within the Shakespearean rhizome, the Shakespearean text is an important element but not a determining one; it becomes less a root than a node which might be situated in relation to other adaptational rhizomes.”45 Visual and graphic adaptation thus form part of non-Shakespearean rhizomes and do so in aparellel worlds. As the wasp and orchid metaphor in a Thousand Plateaus, the Shakespeare text and contemporary digital imagery can interact but do not have to converge to get mutually cross-fertilised.

38Emojified plays, Dan Carroll’s and Good Tickle Brain’s Shakespeare adaptations − and even Table Top Shakespeare’s unextraordinary household items − are part of an ever expanding spectrum of graphic and multimodal approaches to retelling the plays, each of them being rhizomatic nodes. As adaptations they tend to reclaim youthfulness of the protagonists and possibly of the target audience too but are likely to cater to a large range of audiences, which does preclude neither adults, nor Shakespeare scholars. Their common ground is the Shakespearean rhizome rather than the text and as such they can share it as they will for they all expect their readership to feel edutained46 with panels, pixels, and minimalistic (stick) figures.

Bibliographie

FALGAS, Julien, « Et si tous les fans ne laissaient pas de trace. Le cas d’un feuilleton de bande dessinée numérique inspiré par les séries télévisées », Études de communication [En ligne], 47 | 2016, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2018, consulté le 07 février 2019. URL. DOI.

FAZEL Valerie M. and GEDDES Louise (eds.), The Shakespeare User. Critical and Creative Appropriations in a Networked Culture, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

FULLER, Glenn, “Meta: Aesthetics of the Media Assemblage”, Platform: Journal of Media and Communication, Volume 6 (2015), p. 73-85.

GARBER, Marjorie, Shakespeare and Modern Culture, New York, Pantheon Books, 2008.

Hutcheon, Linda and O’Flynn, Siobhan, A Theory of Adaptation, Second Edition, Abingdon, Routledge, 2013.

JENKINS, Henry, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, New York, New York University Press, 2006.

JENKINS, Henry, Sam Ford & Joshua Green, Spreadable Value and Meaning in a Network Culture, New York & London, New York University Press, 2013.

JENKINS Henry, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, New York, Routledge, 1992.

JENSEN, Michael P., “Shakespeare and the Comic Book”, in Mark Thornton Burnett, Adrian Streete, Ramona Wray (eds.), Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2011, p. 388-408.

KAPITANIAK, Pierre, “Hamlet dans la culture populaire : le cas du Stick Figure Hamlet de Dan Carroll”, Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [En ligne], 34, 2016, mis en ligne le 10 mars 2016. URL. DOI.

LANIER, Douglas, Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture, Oxford, OUP, 2002.

LANIER, Douglas, “Shakespearean Rhizomatics, Ethics and Value”, in HUANG Alexa and Elizabeth RIVLIN (eds.), Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, p. 21-40.

LEVENSON, Jill and Robert ORMSBY (eds.), The Shakespearean World, London, Routledge, 2017.

MORTIMER-SMITH, Shannon, “Shakespeare Gets Graphic Reinventing Shakespeare through Comics”, in Gabrielle Malcolm and Kelli Marshall (eds.), Locating Shakespeare in the Twentieth-Century, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012.

MULLER, Anja (ed.), “Shakespeare Comic Books: Visualising the Bard for a Young Audience”, in Adapting Canonical Texts in Children's Literature, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, p. 95-111.

NEWELL, Kate, Expanding Adaptation Networks: From Illustration to Novelization, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

NGAI, Sianne, Our Aesthetic Categories. Zany, Cute, Interesting, Harvard, Harvard University Press, 2012.

ROKISON-WOODALL, Abigail, Shakespeare and the Graphic Novel, Shakespeare for Young People: Productions, Versions and Adaptations, London, Arden Shakespeare 2013.

SHAKESPEARE, William, Hamlet, adapted by Alex A. Blum, Classics Illustrated 87, New York, Gilbertian, September 1951.

SCHWARTZ, Delmore, “Masterpieces as Cartoons”, in Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester (eds.), Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on a Popular Medium, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2004, p. 52-62.

WETMORE, Kevin. J., “The Amazing Adventures of Superbard: Shakespeare in Comics and Graphic Novels”, in Jennifer Hulbert (ed.), Shakespeare and Youth Culture, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 171-97.

WIFALL, Rachel, “Introduction: Jane Austen and William Shakespeare – Twin icons?”, Shakespeare, vol. 6, n°4, 2010, p. 403-409, DOI.

Webography

Polygon: URL.

Borrowers:

Bardfilm: URL.

Reduced Shakespeare:

Good Tickle Brain:

Ann Arbor District Library: URL.

Stick Figure Hamlet:

Table Top Shakespeare, 2015: URL.

All sites accessed 10 October 2019.

Notes

1 See for instance Rachel Wifall, “Introduction: Jane Austen and William Shakespeare – Twin icons?”, Shakespeare, vol. 6, n°4, 2010, p. 403-409.

2 Cf. URL. In this article Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne-Guérin show “how and why Shakespeare and LEGO meet in the cinematic and digital worlds to suggest that LEGO Shakespeare is a complex example of the popular culture that Douglas Lanier has termed ‘Shakespop’ (Lanier 2002).”

3 She has been invited to the American Shakespeare Congress, to Stratford and to important Shakespeare-related events in the States.

4 Links to webcomic blog: URL. URL.

5 No Fear Shakespeare is a graphic novels series based on the translated texts of the plays found in “No Fear Shakespeare”. The original No Fear series was designed to make Shakespeare's plays easier to read.

6 ‘YOLO’ being short for “You Live Only Once” which is part of a range of urban expressions that signify Carpe Diem in modern times.

7 There is a video teaser of the YOLO Romeo and Juliet edition on Youtube here: URL.

8 For Table Top Shakespeare reviews and references, see for instance, Tim Etchells, artistic director of Forced Entertainment presenting the project and underlining how it conveys a ‘vivid sense of the arc of the story’. URL.

9 For a definition and discussion of “spreadable media” this web site is very useful: URL.

10 Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford & Joshua Green, Spreadable Value and Meaning in a Network Culture, New York & London, New York University Press, 2013, p. 236.

11 Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture, New York, Routledge, 1992, p. 46.

12 Members of Patreon are artists who seek a relationship between themselves and their most engaged fans and who do more than just following on social media. They become paying patrons in exchange for exclusive benefits offered by the artists. Mya Gosling invites the visitors of her site to become in her own terms “my personal Earl of Southampton”: URL.

13 Julien Falgas, “Et si tous les fans ne laissaient pas de trace. Le cas d’un feuilleton de bande dessinée numérique inspiré par les séries télévisées”, Études de communication [En ligne], 47 | 2016, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2018, consulté le 07 février 2019.

15 Scroll down the page at URL. Stratford Festival 2017 Photo Comics (part 1), September 5, 2017. May Gosling informs readers about her theatre going activities in Stratford. “It's ‘Stay Sane September’! That means I'll be sharing some of my ‘greatest hits’ from social media and Patreon to keep you entertained while I take the month off in order to avoid burnout, take some theatre trips, and get caught up on various tasks and projects that I have been neglecting. Today's installment features some comics I put together during my trip to the Stratford Festival two weeks ago. I deliberately didn't take my computer so that I wouldn't be able to work. However, once I got there I found myself wanting to document my theatre-going, so I downloaded all the official production photos, ran them through a basic comic app, and here they are.”

16 Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories. Zany, Cute, Interesting, Harvard, Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 41.

17 Ibid., p. 26.

19 Despite their use to signifiy emotional states, emojis do not stem from the word emotion but from the Japanese concatenation of E=picture and moji=letter or character.

20 Three other Shakespeare plays have been adapted in the same way: Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet.

21 This is the link to her web page where the one-sheet emoji versions of the plays can be seen: URL.

22 This short video shows how difficult it is to read text interspersed with emojis: URL.

23 Glenn Fuller, “Meta: Aesthetics of the Media Assemblage”, Platform: Journal of Media and Communication, vol. 6, 2015, p. 82.

24 Ibid., p. 79.

25 See for instance Alexis Tadié, Sterne’s Whimsical Theatres of Language, Aldershot, Ashgate, 2003.

26 See for instance the page which parodies and adapts “The Room Where It Happens” from Hamilton. URL.

28 The Pirates of Penzance was composed in 1879.

29 She published during the month of May 2019 a series of comics on Marvell.

30 The metaphor of the sandbox is recurringly used by Mya Gosling to refer to her vision of what Shakespeare has to offer in terms of adaptation environment. URL.

32 For a more detailed discussion of Chast’s 2002 cartoon, see Marjorie Garner, Shakespeare and Modern Culture, New York, Pantheo Books, p. 58-61.

33 URL. In particular the scene with the three witches from Macbeth, and the incomprehensible verse “For none of spam born shall ham Macbeth”. URL.

36 This is Juliet’s iconography page: URL; Othello is presented here: URL.

37 Macbeth, I.3.82, Complete Works of William Shakespeare, The Alexander Text, London, Harper Collins, 1994, p. 1053.

39 “(Stick figures don't do ‘metatheatrical’ very well....)”. URL.

40 Valerie M. Fazel and Louise Geddes (eds.), The Shakespeare User. Critical and Creative Appropriations in a Networked Culture, London & New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, p. 10.

41 Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn, A Theory of Adaptation, London & New York, Routledge, 2013, p. 121.

42 Douglas Lanier, Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture, Oxford, OUP, 2014, p. 29, citing Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s definition of a plateau.

44 Alfred Uhry’s quote used as epigraph by Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn seems to be contradicted by Mya Gosling’s Shakeapereana “Adapting is a bit like redecorating”.

45 Douglas Lanier, op. cit., p. 29.

46 A word newly coined, stemming from “edutainment”.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Brigitte Friant-Kessler

Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)