- Accueil

- > Shakespeare en devenir

- > N°14 — 2019

- > I. Adaptations théâtrales

- > Some Hispanic Versions of Romeo and Juliet: Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Montesco y su señora, Nacahue, and Romeo & Juliet

Some Hispanic Versions of Romeo and Juliet: Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Montesco y su señora, Nacahue, and Romeo & Juliet

Par Laureano Corces

Publication en ligne le 18 février 2022

Résumé

“Some Hispanic Versions of Romeo and Juliet” analyses four dramatic texts based on the Shakespearian classic. Three of the selected case studies are Latin American works and the fourth case study is a Jewish version where the culture of Spain is present through its influence on Sephardic society. This study evaluates how Romeo and Juliet’s story of romantic love continues to speak to different audiences as it is shaped by the circumstances of the individual societies where the action takes place. Scenes set in Revolutionary Cuba juxtaposed to the representation of the Ecuadorian bourgeoisie allow us to see how the Cold War scenario informed the plot and character development of each of these individual versions in different ways. Similarly, in more recent times, the lovers adopt foreign languages, both in indigenous Mexican communities and in the Jewish diaspora, to tell their tales of individual love. In both instances, we are dealing with specific communities within larger nations and ethnic groups. How each of these dramatic works is framed by its specific sociocultural reality will be explored to reveal how the Shakespearian original play continues to inspire playwrights in contemporary times.

Cet article analyse quatre pièces de théâtre qui s’appuient sur le classique shakespearien, Roméo et Juliette. Trois des études choisies sont des œuvres latino-américaines et la quatrième est une version juive où la culture hispanique est présente à travers son influence sur la société séfarade. Cette étude s’intéresse à la façon dont l’histoire d’amour romantique de Roméo et Juliette continue à parler aux différents publics et ce, parce qu’elle est façonnée par les événements qui surviennent dans les sociétés contemporaines où l’action se situe. Des scènes se déroulant dans le Cuba révolutionnaire où au sein de la bourgeoisie équatorienne nous permettent de voir la façon dont le scénario de la Guerre Froide nourrit le développement de l’intrigue et de la caractérisation dans chacune de ces versions, quoique de façons différentes. De même, plus récemment, les amants parlent des langues étrangères, tantôt issues des communautés mexicaines indigènes, tantôt de la diaspora juive, afin de raconter leur histoire d’amour. Dans chaque cas, cela concerne des communautés spécifiques à l’intérieur de nations et de groupes ethniques plus vastes. La façon dont toutes ces œuvres théâtrales s’insèrent dans une réalité socioculturelle sera explorée afin de révéler de quelle manière la pièce de Shakespeare continue d’inspirer les dramaturges d’aujourd’hui.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Some Hispanic Versions of Romeo and Juliet: Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Montesco y su señora, Nacahue, and Romeo & Juliet (version PDF) (application/pdf – 2,8M)

Texte intégral

1Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, or versions that draw upon this Elizabethan text, seem to have a mythical dimension, in accordance with Joseph Campbell’s assertion that “myths are clues to the spiritual potentialities of human life”.1 These texts explore the experience of romantic love and the willingness of two individuals to take the journey propelled by this rapture.

2While most versions of Romeo and Juliet are anchored in a specific place and time, it is the dimensions of the protagonists’ individual passions that make these stories universal. Moreover, it is the power of romantic love that often distances the protagonists from quotidian concerns and situates them at the margins of their social spaces. Their passions distance them from community life as they explore the mutual connection that makes them feel most alive. Like the lovers in a bubble in Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, Romeo and Juliet rise above their surroundings, not allowing themselves to be separated by the gravity of, for example, family feuds and clannish concerns that would otherwise be obstacles to their union.

Hieronymus Bosch, Fragment of The Garden of Earthly Delights

Crédits : Museo Nacional del Prado

3These stories show us how romantic love can disrupt the social order as they focus on how the lovers transgress societal norms and rules, and in so doing they inform us as to what specific communities hold to be of importance. Therefore, to rewrite Romeo and Juliet would necessarily entail plotting out the tensions between individuals and their society. And, while the reader/spectator’s main focus is most certainly on the couple, the influence of others and how their desires and fears shape outcomes also comes to the fore. It is for these and other reasons that Shakespeare’s text continues to invite authors around the world to represent the passion between two lovers as they also explore how their relationship plays out in a new context. In some instances, there is much fidelity to the original text while in others it simply offers a point of departure from which to begin a new journey.

4It is also important to mention that rewriting Romeo and Juliet does not result in a text that only points toward Shakespeare’s tragedy, but rather that the Elizabethan play exists in a web of representations where romantic love takes centre stage. These representations span all modes of artistic expression, although I am essentially considering literary texts, and go hand in hand with Shakespeare’s version of the ill-fated lovers. Hence, Pyramus and Thisbe, Hero and Leander, from classical antiquity, as well as Tristan and Isolde, a medieval version of star-crossed love, all come to mind. Indeed, the web of texts in which the Shakespearian play is inscribed expands in both temporal and spatial dimensions. To be clear, Shakespeare’s play invites us to look toward the distant past as well as to more recent periods of time as it also shifts our gaze from one location to another.

Some Hispanic versions of romantic love

5It would be fair to say that most of the literary representations of romantic love in Hispanic texts have not projected themselves internationally with the same degree of success ascribed to Romeo and Juliet. Moreover, it seems as though Spain monopolizes the texts on romantic love in the Spanish speaking world. An internet search in Spanish for the term amantes famosos en la literatura (famous lovers in literature) does list multiple websites that do reveal four or five couples who hail from the Hispanic literary tradition. Hence, Don Quijote and Dulcinea (from Don Quijote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes), Calisto and Melibea (from La Celestina by Fernando de Rojas), Don Juan and Doña Inés (from Don Juan Tenorio by Jose de Zorrilla), and Juan Diego and Isabel (from Los amantes de Teruel by Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch) do appear on these websites in Spanish. Yet, a similar search using the same term in English, which also points to a series of websites, does not include any of the aforementioned Hispanic texts. In the Spanish-language websites Romeo and Juliet do appear alongside the other famous couples. Indeed, Shakespeare’s play is well known to Hispanic audiences, and so are the Spanish texts listed above that deal with similar subjects.

6While Don Quijote and Dulcinea would be widely recognized, it is true that these characters from the pages of Cervantes do not share experiences that would characterize them as full-fledged romantic lovers. On the contrary, Don Quijote meets Aldonza once, a country girl from a neighbouring village, and selects her as the lady to whom he will be devoted in accordance with the conventions of courtly love. Within the context of the novel, it is clearly a parody of similar loyalties, between the knight and his maiden, found in the novels of chivalry, the very texts that drove Don Quijote mad. Similarly, the relationship between Don Juan and Doña Inés differs in important ways from the Romeo and Juliet model. These characters from José Zorrilla’s Don Juan Tenorio, a rewriting of Tirso de Molina’s El burlador de Sevilla (the Golden Age play that introduces Don Juan) do not share equal importance in the development of the plot. While Don Juan’s philandering is the main focus of both dramatic texts, it is only in Zorilla’s version that Doña Inés appears toward the end as a deus ex machina to save Don Juan, through the power of love, from damnation. Their rapture and its consequences do not inform the plot in the essential way that occurs in the Shakespearian classic, and that is honoured in subsequent versions based on the Elizabethan text.

7Therefore, only two Hispanic plays featuring famous lovers do fit in more closely with the Romeo and Juliet model. These are plays where the couple’s relationship is explored as an essential element of the plot, where the action from beginning to end addresses their passions and its consequences, and where romantic love does have a tragic denouement. La Celestina, a product of the end of the 15th century tells the story of Calisto and Melibea. Racing after a falcon, Calisto finds himself in Melibea’s garden where he sees the young lady and is love-struck at first sight. He enlists the help of la Celestina, a matchmaker and brothel owner, who claims to have magical powers. Calisto’s love is reciprocated. Both he and Melibea furtively meet. There are also scenes in Melibea’s garden where from her balcony, she looks down on her lover, but their union is cut short when Calisto falls from the ladder leading up to the walls surrounding her garden to meet Melibea. She, upon the discovery of her lover’s death, jumps to her death from the top of a tower. Like the Shakespearean tragedy, romantic love leads to the destruction of the couple.

8Similarly, Los amantes de Teruel pair up Isabel de Segura and Diego de Marcilla in a love that will lead to their deaths but will also immortalize it. The 19th century play is based on a medieval legend. Isabel and Diego fall in love at first sight, but given Isabel’s wealth and Diego’s limited means, Isabel warns that her father will not accept the union. Diego decides to go out into the world to seek fortune and thus return to marry Isabel. Although he succeeds, upon his return he discovers that Isabel has been forced to marry a wealthy suitor (she had put off the wedding with excuses, but her father’s pressures finally resulted in the union). Nevertheless, he goes to see her and asks for a kiss, which she refuses to give since she is now a married woman. Her denial results in his death. Guilt-ridden and still passionately in love, Isabel goes to the church where Diego’s body lays and kisses the corpse. As she embraces him, she also dies.

9Both La Celestina and Los Amantes de Teruel hold a special place in the collective memory of the Spanish speaking cultures that stands alongside Romeo and Juliet as they focus on romantic love and the impossibility of its success. Both texts are staged from time to time, and film versions exist. However, one could argue that both texts do not distil the essence of romantic love as effectively as in Romeo and Juliet. La Celestina is a very long text, a reality that has incited critics to argue as to the text’s genre, as to whether it should be considered a drama or a novel with dialogue. So, for example, Marcelino Menendez Pelayo includes La Celestina in his study on the origins of the novel, Origenes de la novela (1905–1915). Moreover, like Los amantes de Teruel the presence of subplots distances the reader/spectator from the main plot. Perhaps, the success of Shakespeare’s text has much to do with its economy, its direct representation of the lovers’ glory and destruction.

Resituating Romeo and Juliet in the Hispanic tradition – four case studies

10At different moments, and in different nations, playwrights have perceived the impact of Romeo and Juliet as one that does not wane. The play offers these artists an outline for their creative projects and with varying degrees of fidelity to the original, derivative texts have been written. While this article does not intend to review the full array of literary works based on Romeo and Juliet, it does attempt to show how specific versions do create a dialogue with the societies in which they are inscribed. Before I start to assess each individual literary work, some general comments would be helpful.

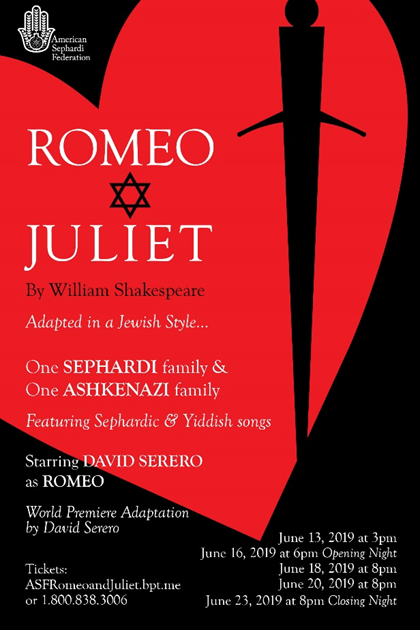

11To begin with, it is important to note that three of the selected case studies are Latin American works and the fourth case study is a Jewish version where the culture of Spain is present through its influence on Sephardic society. All four are dramatic texts, like Shakespeare’s original. Therefore, each individual text was created to be performed, a fact that I will take into account in my analysis. In other words, although I am reviewing the written texts, I do consider that additional levels of meaning may be added through their theatre productions. Interviews with the creators of Nacahue and the Jewish Romeo and Juliet were helpful to better understand what can happen when the text is brought to life on a stage. The analysis of the Jewish version is based on an interview with David Serero, who adapted and directed it. This is a work in progress that will have its international debut in June 13, 2019 at the Center for Jewish History in New York. Similarly, Juan Carillo, the director of Nacahue, was instrumental in clarifying the performance history and directorial decisions that went into staging his Mexican version of Romeo and Juliet.

12While there is no doubt that romantic love is at the heart of these versions, it is also true that intolerance, or lack of understanding, inform these texts. My study juxtaposes two texts that are closely related to the Cuban Revolution and are framed within the context of the Cold War, more specifically 1965-1985. Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, a collaborative project under the direction of Cheo Briñas was first peformed in 1981 and takes place in Communist Cuba, while Montesco y su señora by José Martínez Queirolo appeared in 1965 as an Ecuadorian response to the perceived ills of bourgeois society. Therefore, these two plays provide us with some idea as to the political realities and the prevailing discourse in Latin America during this period. Depictions of capitalist society´s consumerism, in the Ecuadorian play, contrast with representations of Cuba and its Revolution in the collaborative piece. Indeed, these works reflect the greater political tensions of a world that was for the most part divided between the Soviet bloc countries and the Western nations with the United States in the lead. My study also moves forward to our current decade to see how Romeo and Juliet continues to provide the foundation for a Mexican version where indigenous communities and the boundary between them are the backdrop of the lover´s union in Nacahue (first performed in 2017). Similarly, in the Jewish version (performed in June 2019), the differences between Sephardic and Ashkenazi cultures frame the connection between the two lovers. Interestingly enough, these most recent versions include languages other than English and Spanish as the Mexican play juxtaposes Cora, an indigenous language to Spanish and the Jewish adaptation contains words in Ladino and Yiddish. So, these versions include a linguistic expansion that represents local realities contrasting sharply with an increasingly globalized world.

Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó: A dialogue with the Cuban Revolution

13The Grupo de Teatro Cheo Briñas is undoubtedly a child of the Cuban Revolution. The company was founded only one year after Fidel Castro took power, yet their play, Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, based on the Shakespearean classic, was performed in 1981. By the time the play was staged, Cuba’s state-controlled communist economy and the cultural changes resulting from the Revolution were solidly in place. The individualism of capitalist economies had been replaced by a more collective force influencing all social exchange. This is evidenced in the plot where, as a result, Romeo and Juliet, who now bear the names Felipe and Odalys, must answer to the community, to their neighbours who play an increasingly important role in post-revolutionary Cuba. Therefore, in addition to the focus on the two protagonists, the reader/spectator confronts a series of neighbourhood characters who help “stage” the drama of Felipe and Odalys. Indeed, at the beginning of the play a chorus announces that Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó is a collective creation.2

14Early on, the audience is informed that they are viewing members of a CDR (Comite de Defensa de la Revolucion (Committee for the Defence of the Revolution). Carmen, one of those attending the meeting, states that “Este es nuestro CDR, pero puede ser el tuyo” (“This is our CDR, but it could be yours as well”).3 Although she is one of the neighbours, this character takes on a choral function providing the audience with background formation. She goes on to explain that the neighbours get along well, that most have lived in the community for years, and that only a few families have moved in recently.4 The Committees for the Defence of the Revolution played an increasingly important role in Cuban life as the eyes and ears of the Revolution. Fidel Castro defined these groups as “a collective system of revolutionary vigilance”.5 Among other activities, these block and neighbourhood associations monitored the activities of residents, mobilized the population for government demonstrations, provided for information on health programs, and organized community projects and celebrations. The action, as Carmen states, could have taken place anywhere in Cuba as the CDRs were ubiquitous under the Castro regime. Nevertheless, towards the end of the play, a reference to el Vedado, mentioned by one of the characters who must run an errand in this Havana neighbourhood, helps to locate the action in or near the Cuban capital. Moreover, the title of the dramatic work includes the place name “Luyanó”, a working-class suburb of Cuba’s capital.

15The neighbours have convened to collectively rid themselves of unnecessary things in an activity called plan tareco.6 Individuals are bringing forth items that are no longer needed or useful. Later on in the play, there are references to the extermination efforts carried out by the community to rid the neighbourhood of insects that may carry diseases. Hence, the play begins with collective activity, with the mobilization of the community towards common goals. It is interesting to note that both projects, plan tareco and the extermination activity result in the elimination of unwanted and harmful things. One may view this opening scene, where ridding oneself of undesirable objects is performed, and in this case as a collective activity, as a sort of cleansing ritual. Indeed, the momentous changes introduced by the Cuban Revolution involved both the elimination of national traditions and individual habits as well as the transformation of social practices and activities. With this in mind, the text may be read as one whose discourse reveals how collective decision-making defines what should remain and what should disappear.

16This process of triage, for which plan tareco serves as an allegory, was essential towards defining the national ethos as Cuban society moved away from capitalism and embraced communism. At the same time, underscoring what would be acceptable under the new rules and norms of the revolutionary society, both in terms of belief systems as well as individual behaviour and actions, was key in consolidating dictatorial rule. Yet, this process of consolidation and definition often took place with the input of the Cuban people or, at least, efforts were made to make it appear as though the masses had much input as to Cuba’s future. To be sure, Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó reveals the power the community exerts on individuals as each step the young couple takes is reviewed and commented upon by the community.

17The increasing importance of the community in Cuban life is represented in the structure of the play. The members of the CDR frame and perform the story of the young lovers. So, for example, Carmen introduces the action by informing the reader/spectator:

There’s something that we need to resolve. You see that girl over there… she’s Odalys, a good revolutionary, a good daughter… And that other youngster is Felipe, like Odalys he’s also a good student, a good son… The problem is that Odalys and Felipe after so many encounters, after a good number of conversations at the bus stop, at student events… well, they fell in love, like so many others, and then…).7

18It is telling that Carmen should perceive the couple’s situation as something that the community needs to resolve. In a society where individual desires were often eclipsed by societal needs and concerns, the private lives of Odalys and Felipe are magnified for all to see and for communal input. Furthermore, let us note how Carmen’s words point to love as a problem. We will later see that the couple’s love is complicated by their parents, more specifically Felipe’s father; but this is not mentioned in her introduction. And yet, the fact that they both fell in love is identified at the very beginning as a “problem” requiring a solution.

19Carmen also functions as a director calling on Odalys and Felipe to re-enact specific scenes of their relationship with the help of the members of the CDR. She asks for volunteers to play the roles of the respective parents. She probes to see what transpired and as different versions emerge, from the point of view of Odalys and the point of view of Felipe, these are performed by the collective. Throughout, a revolutionary optimism emerges. Hence, the community does not oppose the lovers’ passion. So, when Odalys states: “We love each other, but it’s impossible”, Carmen responds: “Could there be anything that’s impossible for Cuba’s youth today?”8 The rhetorical question speaks to the new possibilities the Cuban Revolution opened up for many of its citizens. It is a statement about a large constituency, Cuba’s youth, and an important one as the play explores how an individual situation, Odalys and Felipe’s relationship, fits in, and is mediated by, the direction the community/nation is taking. In this version, the couple’s passion is as important as the community’s aspirations, configured by the new goals of a nation exploring uncharted territory.

20The challenge Odalys and Felipe face is directly linked to the political situation in Cuba after the Revolution. While the exact time the dramatic action represents is not clear, the text does illustrate the fervour of the Revolution as well as the dissent of those who opposed communist rule. Felipe’s father, Cesar, plans to leave Cuba for the United States. He also wishes to take his son with him. His anti-revolutionary stance is the cause of much friction between Odalys and Felipe and leads to a series of misunderstandings. For example, Odalys had considered not to tell her parents about Cesar’s plans, yet when she finally confides in them it results in much turmoil at home. Similarly, conversations between Odalys and Felipe take off on tangents with negative repercussions. That the decision to exile oneself should be anathema to those who support the Revolution comes as no surprise especially given the highly politicized nature of human relationships and the ideological divisions that were magnified after Castro came to power.

21While the conflicts arising from Cesar’s decision to leave Cuba do take centre stage, an optimistic tone looms over the individual tensions in Odalys and Felipe’s respective households. Let us not forget that this is a group theatre project, and it is also important to mention that the dramatic representation is highly influenced by Bertolt Brecht. The alienation effect is effectively used as the members of the CDR both comment on and perform the scenes of Odalys and Felipe’s courtship. The text imagines performances where the spectators are constantly reminded that they are viewing an enactment of real events. As a result, an emotional distance is created where the challenges that the young couple faces are not so much felt by the audience, but rather displayed for analysis. The Elizabethan text does not inform the dialogue, yet the plot is to some degree traced, albeit with free strokes, on the Shakespearian original. Throughout, there are comments that stress the ethos of the Revolution reminding Odalys that her future does not depend on a man, that going on with her education is important, and she instructs Felipe to do what he truly feels regardless of his father´s pressures. This discourse is embraced by Felipe who expresses his intentions to study engineering so as to serve the Cuban people. He is not interested in leaving Cuba for a well-paying job in the United States as his father would have preferred. Hence, Felipe articulates an ideology that is informed by socialist precepts.

22Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó departs from the Shakespearean text in fundamental ways. The differences between the Cuban text and the original illuminate the new context, one that also shapes the destinies of the protagonists. At all points in time, the reader/spectator is fully aware of the transposition to a new place and time. As one might imagine, the denouement is not tragic. Cesar does leave for the United States, but Felipe and his mother remain in Cuba. Carmen informs the audience at the very end of the play that both Odalys and Felipe went on to get married and that their marriage was celebrated by the entire neighbourhood. The stage directions indicate that the party celebrating their union should be represented. Therefore, in Revolutionary Cuba a couple very much like Romeo and Juliet need not suffer the tragic destiny that the Shakespearean text had reserved for its protagonists. On the contrary, by mitigating the importance of the family conflicts and with the positive input of an entire community these individuals are allowed to bond in a union which serves as a metaphor for social changes that are perceived as positive. Thus, Shakespeare’s myth of Romeo and Juliet is appropriated to illustrate that life, and romantic love, have changed in essential ways as a result of the Cuban Revolution.

Montesco y su señora: a bourgeois version of romance and its aftermath

23Montesco y su señora (Montesco and his Wife) by José Martínez Queirolo was written in 1964 and staged shortly afterwards as a tribute to the four-hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. The author hails from Ecuador where a right-wing junta had seized control in 1963. Prior to a shift to the right and dictatorial rule in Ecuador, Arosemena Monroy, a democratically elected president, had maintained relations with Cuba. For this, and other reasons, he was labelled as a communist, and finally deposed by a military junta whose anti-Communist agenda shaped the nation’s institutions and culture. It is important to keep in mind that the Cuban Revolution and its aftermath were inscribed within the context of the Cold War. Geopolitical conflicts were played out on Latin American soil in a variety of ways. So, for example, dictatorial rulers often sought legitimacy as defenders of capitalism with staunch anti-Communist positions; yet many of Latin America’s intellectuals were sympathetic to the Cuban Revolution, especially during the early years. José Martinez Queirolo’s “sequel” to Romeo and Juliet evidences a critical stance on bourgeois society. Indeed, the Ecuadorian playwright’s repertory includes plays that portray the mass media and American cultural hegemony as undermining the cultural authenticity of his nation. Similarly, he focuses on the Ecuadorian family and the institution of marriage, to unmask the hypocrisy that underlies many social conventions and performances in Latin American society.

24It is also important to emphasize that Montesco y su señora is not exactly a rewrite of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, but rather a sort of sequel based on the original text. For a start, the action takes place when the couple is in their fifties. The dialogue helps to clarify as to the individual destines of the protagonists, one where each of them survived. In Romeo’s instance, a gastric lavage succeeded in eliminating the poison and some stitches warded off infection and death in Juliet’s case. As a result, we find the couple alive, but not well, many years later.

25Like in Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Martinez Queirolo relies on the alienation effect to distance the audience from the action of the play. As noted earlier, this Brechtian resource encourages spectators to take a more critical stance as they are not duped by realistic representation and do not confuse mimesis with real actions and situations. Therefore, it is clear that there is an attempt to influence the audience, In this vein, the stage directions state that Juliet’s voice is heard inviting spectators to witness “our tragedy’ (“nuestra tragedia”), “our real tragedy” (“nuestra verdadera tragedia”).9 The stage directions instruct that the curtains come up so as to reveal Romeo and Juliet in their bedroom (a bald Romeo, a visibly aged Juliet) in pyjamas. On the walls, there are portraits of the Montagues and Capulets. Romeo is furious about the prospect of having their lives play out in front of an audience. Yet, the play goes on.

26Early on in the dialogue the romantic couple subverts the discourse on romantic love. They address the young people in the audience and warn them about the loss of freedom, the prospect of falling out of love, the certainty of aging bodies and changing personalities and other disillusionments connected with the trap of infatuation and the consequences of marriage over time.10 Clearly, this is a humorous account that goes against the grain of the Elizabethan original where the tragic denouement precludes the long-term consequences of youthful love. At the beginning of the play, the death scene is re-enacted, but Romeo and Juliet survive. Moreover, Martinez Queirolo establishes links with specific scenes in the original text as he quotes freely from Shakespeare’s tragedy. Needless to say, the intertextuality functions to create a parody of the original as the romantic verses clash with the discordant reality of the couple many years into their relationship.

27As Romeo and Juliet’s lives go on, the spectator witnesses that many of the frustrations that poison their relationship are the result of economic difficulties. We learn that Juliet had lived a pampered life with her parents, one with an abundance of goods. Yet, Romeo has not been able to offer her the same level of economic stability. She complains about their limitations, and we discover that, to make matters worse, he is presently unemployed. The contrast with Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó is striking. In the Ecuadorian version, the action takes place within the context of a Latin American capitalist society where individual happiness is represented as inextricably linked to consumption, to the purchase of and possession of goods. Martinez Queirolo’s couple is clearly not proletariat (despite the references to some degree of economic limitation, they seem to belong to the upper-middle class) whereas the neighbourhood in the Cuban version is working class. Economic challenges are present in the Ecuadorian play while the representation of economic hardship is absent from Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó.

28Not only are the economic challenges in Montesco y su señora the result of unemployment or other immediate circumstances, but rather inheritance comes to the fore as an important issue. The text appropriates the verses from Act II in the original “Deny thy father and refuse thy name” (2.2.37) to shape the action in the Ecuadorian version.11 We discover that Romeo had followed Julieta’s instructions and disinheritance was the result of renouncing his family’s name. Therefore, their relatively precarious economic situation originates in an idea proposed in the Shakespearean text with its modern twist so as to subvert the original intention of the dialogue.

29This intertextuality structures portions of the dialogue in Martinez Queirolo’s version. So, for example, Julieta claims that their ill-conceived marriage was spurred by their parents’ opposition. Similarly, Benvolio and Mercutio are still around, and Señor Montesco socializes with them at the expense of time spent at home with his family. Moreover, it seems that he is having an affair with a woman whose name is Rosaline, the same name given to the young lady with whom Romeo was in love before he met Juliet in the original version.12 And, perhaps more importantly, Martinez Quierolo signals the archetypal nature of human relationships as the couple’s daughter is being wooed by a young man who shouts up to her balcony with Shakespeare’s original lines. In the Ecuadorian play, Julieta hears the voice of a young man reciting the verses at the beginning of Act 2, scene 2.13 It seems as though history will repeat itself, or will at least rhyme, in ways in which establishing a relationship with Shakespearean drama helps us to better understand a specific period of time in Latin American society as the new version explores the reversal of romantic love.14

Nacahue: An indigenous dialogue with Shakespeare

30The Mexican theatre company Los Colochos Teatro, created in 2010, is exploring the connections Shakespearean texts establish with audiences as they continue to confirm the relevance of his works in today’s societies. Based in Mexico City, the group performs internationally and is presently working on plays based on the bard’s classics. Mendoza resituates Macbeth in a Mexican cantina (saloon) during the Mexican Revolution as the violence depicted in this version also recalls more recent massacres in Mexico. Adapted by Antonio Zuñiga and Juan Carrillo, it has been staged at important theatre festivals such as Almagro, Cádiz, and Bogotá and also performed in the United States. Similarly, the more recent Nacahue: Ramón y Hortensia based on Romeo and Juliet, first appeared at the International Festival of Classical Theatre in Almagro, Spain, in 2017 and continues to tour internationally.15 These two productions are part of a larger project to adapt Shakespearean originals within a Mexican context. The project envisions similar rewritten versions of Othello, Titus Andronicus, and King Lear for international performances.

31Nacahue transfers the action of Romeo and Juliet to the northwest of Mexico around Nayarit. This mountainous and relatively isolated region is inhabited both by the Cora and Huichol peoples. The action takes place during Holy Week, with some reference to Cora traditions during their Judea celebrations. It is important to keep in mind that in many Mexican cultures native religions have blended with Catholicism to create a syncretic system of beliefs and religious traditions. Therefore, the Christian Holy Week includes rituals that evidence indigenous influence. So, for example, a specific ceremony during the Judea, the name given to celebrations and rituals honouring the death and resurrection of Christ, requires Cora participants to paint themselves, thus symbolically erasing their human identity, to embody spiritual beings. The ceremony culminates with their washing off the paint so as to return to human form, a cycle that is closely linked to pagan harvest rituals and now enacted within the context of Easter week. When Hortensia first meets Ramón, his face is painted in accordance with this ritual.

Ramon and Hortensia in Nacahue

Crédits : Juan Carrillo

32Indeed, Nacahue represents the rapture of romantic love between Hortensia and Ramón within a context where the sacred intersects with the profane. Situating the action in indigenous societies where secularization has not changed the way in which individuals closely identify with religious beliefs and customs imbues the text with a timeless quality. References to myth allude to sacred time and human actions seem to be simple and external to a deeper spiritual reality. It is, however, not an accident that romantic love should be situated within this context as the experience of human rapture also appears as a window onto the divine. In this vein, Porfirio, a Cora elder, informs the audience that important things need to be seen with other eyes and heard with other ears. The play itself challenges spectators to suspend traditional means of understanding as it is performed in Cora and in Spanish (although the text I studied was entirely in Spanish). Therefore, a good percentage of the dialogue cannot be understood by most audience members. Indeed, Ramón and the other Cora characters express themselves in their indigenous language, while Hortensia and her Huichol compatriots speak Spanish. The choice to have the latter speak Spanish is merely a dramatic convention as the play would not have been understood by most audience members if completely performed in Cora and Huichol.

33While the decision to juxtapose a little-known Mesoamerican language with Spanish, without the aid of subtitles, sounds risky, the creators of Nacahue did give the matter serious consideration. They made a conscientious decision to place the audience in a situation similar to the one experienced by Hortensia and Ramón. Let us not forget that in this version the avatars of Romeo and Juliet do not speak the same language, and the play stresses that this linguistic gap requires Ramón and Hortensia to communicate beyond linguistic codes. Similarly, the audience is challenged to go beyond spoken language and pay more attention to body language, to the gaze and movements of the characters, among other features, so as to derive meaning from these other modes of communication.

34Toward the beginning of the play, a short discourse on love establishes difference. Fermín, Ramón’s closest friend, described as his putative brother, admonishes Ramón for not contenting himself with a stable, perhaps pragmatic, partnership. Fermín references himself and signals how he and Inés, his wife, have established a solid bond, yet Ramón, according to Fermín, is still waiting for love to fall from the sky. This is a particularly important clarification, because it seems as though Ramón’s potential wife is already by his side. Colia, a woman from Ramón´s village, in an aside to the audience, relates how her destiny was to meet up with Ramón, and how they were happy sharing corn, a home, and love. Yet, she explains that one day she fell ill and was in a state of unconsciousness for an uncertain period of time and when she returned to her home, she was told that she had invented the whole thing as if it were a dream. However, she wonders how a dream could have lasted so long. Colia´s words lack precision, and the reader/spectator is not informed as to exactly what happened. Further dialogue does not substantiate what Colia describes; on the contrary, Fermín simply mentions her as the young lady everyone in the community perceives as “sharing loving smiles” with Ramón. Therefore, Colia’s vision may be interpreted as what could have happened, or simply as a projection of her deepest desires, but not as something that did indeed take place. Nevertheless, it is clear that Colia, a member of Ramón’s community, would willingly join Ramón in marriage. However, in this play destiny has other plans for Ramón.

35On the other side of the river, the boundary between Cora and Huichol peoples, Hortensia has lived a tormented existence with her husband Otilio. In a scene where an individual memory of Otilio is represented, her husband complains about her infertility, he addresses her with aggressive words and whips the back of her body with a dry branch. Further along, a dialogue between Hortensia and her mother establishes the abuse as ongoing and as something that, according to her mother, she will grow to accept. In her refusal to continue in an abusive relationship, Hortensia flees from her home and heads out into the mountains. It is in this natural setting that Ramón encounters her for the very first time. However, he does not see her as a woman, but rather as a deer. Porfirio, an old Cora wise man, tells Ramón that the deer has come in search of him, and that he sees it because his spirit is clean. This takes place during the Judeada, right before the point in time when Ramón loses his identity as an individual to become one with the universe. Porfirio tells him that the deer wishes to communicate, and Ramón responds that he has already experienced something that he had never felt before.

36Afterwards, Ramón and Hortensia do meet by the river, and while a language barrier separates them, the rapture of love unites them. In Nacahue love is represented as an experience that both eliminates fear and transcends boundaries, and finally that enlightens the lovers. The limitations imposed on individuals by closed and isolated communities are expressed in the words Hortensia’s brother, Pascual, shares with her. He does not believe that there is much that is of interest beyond Huichol lands. Nevertheless, Hortensia’s encounter with Ramón has expanded their world in both positive and negative ways. As Hortensia flees, her brother attempts to catch up to her and stop her. Instead, he encounters Ramón, the Other, in a tragic confrontation.

37When Pascual meets up with Ramón, he demands to know what the latter has done with his sister. The language barrier, and heightened emotions, get in the way of clear communication and a scuffle ensues. Fermín comes to Ramón’s defence and is mortally wounded by Pascual and he in turn is killed by Ramón. Shortly, thereafter, Inés, Fermin’s wife wounds Hortensia. Despite the enmity between Hortensia and the Cora women, Porfirio instructs these ladies to care for Hortensia, and to leave her destiny, whether she will live or die, in the hands of the Gods. When Ramón sees Hortensia by the Cora women, he misinterprets the scene and believes they are harming his soulmate. He runs off with her, despite the fact that she is dying. They do not go far as she dies by the river and Otilio, her husband, shoots an arrow from across the river that kills Ramón. Then, the two lovers metamorphose into deer.

38In Nacahue the plot is loosely based on Romeo and Juliet with the important changes described above. The language of the original play does not inform the Mexican version, yet, for example, some of the indigenous beliefs with reference to the moon do recall lines in the Shakespearean version. The idea of having Hortensia run away from an abusive husband is novel. In Los Colochos’ adaptation, romantic love does not need to grow in adolescent hearts but may offer an escape from a weary and destructive domestic life. That all of this is veiled in sacred fabric, with multiple references to the Gods, juxtaposes romantic love to our human attempts towards understanding the great mysteries of life. At the same time, this version illuminates certain aspects of indigenous life in a specific corner of Mexico.

A Jewish dialogue with Romeo and Juliet

39A project that opened in New York in June 2019 is David Serero´s Romeo and Juliet, adapted in a Jewish Style. The Off-Broadway world premiere at the Centre for Jewish History in New York is hosted by the American Sephardi Federation. Although, the play temporally alludes to the Middle-Ages, the time period is not essential toward defining how it is represented. Serero believed that vaguely representing the time of the action allowed him to establish stronger connections with the present. However, he decided to locate the action in Jerusalem, and his willingness to always bring together multi-ethnic casts, as well as a variety of actors, from comic performers to classically trained actors, expanded the dialogue that audience members might establish with his version. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that the conflict in this drama is spurred by the tensions that exist between Sephardic and Ashkenazi families. So, once again, Romeo and Juliet share an individual love that is threatened by the animosity of a larger community.

Poster for the New York premiere of Romeo and Juliet, adapted in a Jewish style

Crédits : David Serrero

40Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardim, are a Jewish ethnic division that refers to the Jewish population that can trace its heritage back to the Iberian Peninsula. In other words, these are essentially the Jews of Spain. Originally, they inhabited different areas of what today is Spain and Portugal, and after their diaspora, have maintained cultural traits linked to these lands. For example, these communities speak languages that are variants of Spanish and Portuguese. Similarly, the presence of medieval versions of both of these Romance languages are present in Sephardic songs. Ashkenazi Jews, or Ashkenazim, on the other hand, are mostly connected to the other side of Europe, the European nations in the East as well as the heart of Western Europe. Like the Sephardim, their history is also one of diaspora, hence they progressively left early settlements in what today is Germany and France to inhabit regions further east. It is for this reason that Yiddish is their main language, a Germanic language that became prevalent in the Ashkenazi communities everywhere.

41In the play, the Ashkenazi are represented as being serious and reserved with dialogue that underscores their intellect while the Sephardim are associated with manual labour, a more familiar mode of behaviour and a special brand of humour. The tensions between these two communities is well known, so this play both depicts the past as it speaks to the present.

42In Serero’s version music underscores some of the differences between the two communities as the Sephardic group sings in Ladino and Judeo-Arabic, while the Ashkenazi sing in Yiddish. Despite the inclusion of songs, the text remains rather faithful to the Shakespearean original, although it has been abridged to result in a ninety-minute production. So, for example, the main characters retain their original names, with the exception of Friar Laurence who is now Rabbi Laurent, as key dialogue from the Shakespearean original informs this Jewish version. At the same time, the text connects with popular culture and establishes links with other texts, especially when this may result in humour. Nevertheless, the denouement is tragic as Romeo and Juliet meet their deaths along the lines of the Shakespearean original.

43It is interesting to note that when Romeo and Juliet meet, he sings to her in Ladino and she responds in Yiddish. Subtitles will not clarify the lyrics. Once again, the audience witnesses a linguistic gap, along the lines of the one we encountered in Nacahue. While the Shakespearean original had prided itself on the clarity, beauty, and eloquence of its dialogues, with words that are understood by the reader/spectator, in these most recent versions the use of foreign languages seems to diminish the importance of oral communication as the sole communicator. With music, the international mode of communication helping to bridge the gap, and audiences being asked to open their eyes and ears to pay careful attention to dramatic signs such as corporal movements and facial expressions, these new versions of the Elizabethan classic reveal how representations of romantic love may move beyond clearly intelligible language to illuminate how love is greater than words.

Conclusion

44The ability of Shakespearean texts to continue to establish dialogues with audiences all over the world is truly impressive. It is also fair to say that Romeo and Juliet continues to be one of the all-time favourites. This tragedy offers international playwrights an opportunity to depict the greater picture, to reveal specific aspects of their societies and their cultures as they focus on the couple’s romantic connection. Indeed, one could argue that Shakespeare’s success in rendering the discourse of love in all its beauty and power is unrivalled; and perhaps the triumph of language in Romeo and Juliet discourages other playwrights from experimenting with poetic language that would sound pale in comparison. Besides, in the versions of the classic that we encounter in this article, quotidian words as well as dialogues that are linked to religious rituals and the sacred construct the dramatic action. In some texts, direct quotes are taken from the Shakespearian original while in others the plot and the dialogues are more loosely based on the Elizabethan play. In all instances, a double-vision does emerge where the reader/spectator is invited to recall certain aspects of the original as s/he confronts a new web of signs with additional meaning. In this regard, new versions of the play are semantically rich as they refer to both the original and its “avatar” that the reader/spectator encounters.

45Given this reality, the frequency with which Shakespeare is revisited should not surprise us, and although the process of rewriting always entails decisions as to what will remain and what will be deleted, it plays an important role in the audience’s appreciation of the new version. Yet, no matter how different a new version of Romeo and Juliet is, the reader/spectator will always have the classical balcony scene looming in their mind. The new socioeconomic realities that come to the fore in new versions, the different political ideologies that are outlined in these adaptations, become the original framework for a constant – the eternal presence of romantic love. In these Hispanic versions, we see how the polarity of Cold War politics results in very different visions of Shakespeare’s play. On the one hand, community thrives and informs each step of the action in the Cuban version; yet an individualistic and isolated couple performs an epilogue to the original, one where Romeo and Juliet are in their fifties. Similarly, in more recent times, a sharper focus on specific ethnic communities shapes the plot, defines the characters, and alters the language in significant ways. It is helpful to recall that in both the Mexican and Jewish versions of the play English and Spanish, are no longer the sole means of expression. Moreover, since the languages that are used in these performances are not always known by the audience, the body language, the movements and gazes among other visual markers take on additional importance.

46In conclusion, audiences will continue to be swept up by witnessing the strong bonds between Romeo and Juliet. That these may be represented in different ways only speaks to the many possibilities that drama can effectively explore. Clearly, a short selection of dramatic texts is only the tip of the iceberg. Nevertheless, in studying selected cases we do begin to see the complexity of rewriting Romeo and Juliet at different moments of our literary history and how these new texts bridge a classic with the realities and concerns of the present.

José Martínez Queirolo and Marina Salvarezza in Montesco y su señora. Produced in Teatro Experimental del Centro de Arte in 2006

Crédits : Picture with courtesy from El Universo (Ecuadorian newspaper) where the picture was published on November 6th 2006

Bibliographie

BRECHT, Bertolt, The theatre of Bertolt Brecht, New Orleans, Tulane University, 1961.

CERVANTES, Miguel de, Don Quijote de la Mancha, ed. John Jay Allen, Madrid, Catedra, 1989.

EDMONSON, Munro S, Nativism and Syncretism, New Orleans, Tulane University, 1960.

HARTZENBUSCH, Juan Eugenio, Los amantes de Teruel, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1992.

OVID, Ovid's Metamorphoses, Dallas, Spring Publications, 1989.

QUEIROLO, José Martínez, José Martínez Queirolo Teatro, Guayaquil, Editorial Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, 1974.

ROJAS, Fernando de, La Celestina, Madrid, Real Academia Española, Galaxia Gutenberg, 2011.

SHAKESPEARE, William, The Globe illustrated Shakespeare: The complete works annotated, New York, Gramercy Books, 2002.

WAGNER, Richard, Tristan and Isolde, London, Riverrun Press, 1983.

ZORRILLA, José, Don Juan Tenorio, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1975.

(No author) Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Grupo de Teatro Cheo Briñas, La Habana, Ediciones Unión, 1987.

Notes

1 Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth. URL.

2 The Chorus states “El Grupo de Aficionados Cheo Briñas presenta: Romeo y Julieta en Luyano! Una pieza de creación colectiva” (The Cheo Briñas theater enthusiasts group presents: Romeo and Juliet in Luyanó! A collective theater project.), p. 8. All translations are mine, unless otherwise cited. Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó, Grupo de Teatro Cheo Briña, La Habana, Ediciones Unión, 1987.

3 Id.

4 She employs the term “permutar” which refers to the process of exchanging houses or apartments in communist Cuba. Such depictions ground the play in Cuba’s individual reality where, for example, housing was not on the free market to be purchased, but rather controlled by the government resulting in such practices as the permuta.

6 The Cuban term “tareco”, which the Dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy defines as a word used in Cuba, the Canary Islands, and Uruguay, essentially refers to a piece of furniture or object that is no longer useful.

7 “... tenemos algo que solucionar. Uds. ven esa muchachita que se encuentra allí… es Odalys, buena revolucionaria, buena hija… Y aquel otro joven es Felipe, igual que Odalys es también buen estudiantes, buen revolucionario, buen hijo… El problema es que Odalys y Felipe de tanto saludarse, de tanto conversar en la parada, en los círculos de estudios… pues se enamoraron, como tanta gente y entonces…”, Romeo y Julieta en Luyano, p. 8.

8 “Odalys : Nos queremos, pero es imposible”.

9 José Martínez Queirolo, Montesco y su señora, in José Martínez Queirolo Teatro, Guayaquil, Editorial Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, 1974, p. 169.

10 It is interesting to note that in both Romeo y Julieta en Luyanó and Montesco y su señora there are references to “youth”. Both plays seem to have a somewhat didactic intention with a message for young adults. While these plays are intended for a broader audience as social theatre, they do seem to focus on creating a dialogue with the younger members of the audience in an attempt to motivate social change.

11 All the references to Shakespeare’s text come from William Shakespeare, The Globe illustrated Shakespeare: The complete works annotated, New York, Gramercy Books, 2002.

12 Benvolio, in 1.3.89-90, tells Romeo that Rosaline is at the Capulet’s feast: “At this same ancient feast of Capulet’s / Sups the fair Rosaline whom thou so loves”.

13 These are rendered in a Spanish translation of “. . . what light through yonder window breaks? / It is the East, and Juliet is the sun. / Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, / Who is already sick and pale with grief / That though, her maid, art far more fair than she” (2.2.2-6).

14 James George Eayrs attributes the quote “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” to Mark Twain in his book Diplomacy and its Discontents, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1971, p. 121.

15 In Spanish: Festival Internacional de Teatro Clásico de Almagro.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Laureano Corces

Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)