- Accueil

- > Shakespeare en devenir

- > N°9 — 2015

- > The Genesis of Macready’s Mythical Lear : the New Tragic Lear, according to his 1834 Promptbook

The Genesis of Macready’s Mythical Lear : the New Tragic Lear, according to his 1834 Promptbook

Par Gabriella Reuss

Publication en ligne le 10 mai 2016

Résumé

William Charles Macready’s restoration of King Lear in 1838 was indeed a mythical production, which, sweeping Nahum Tate’s happily ending adaptation of King Lear off the boards at once, changed for ever the paradigm of both appreciating Shakespeare and acting King Lear for ever. Nonetheless, no matter how famous and erudite Macready was, or how illustrious his literary and theatre friends were, he had to go against the long tradition of Nahum Tate’s melodramatic version when he endeavoured to restore the original text. It is much less known however, that Macready experimented with the tragic plot and the Shakespearean text as early as in 1834 at his benefit nights to promising critical reception, and that Macready’s promptbook of the 1834 production exists in the Duke Humphrey Archives of the Bodleian Library. Having examined the author(s) and the handwriting(s) of this promptbook in earlier publications, in this paper I will shed light on Macready’s rendering of the title character in 1834 and in 1838 from his promptbooks. The way Macready acted the vigorous and energetic aging royal, and the way he performed Lear’s death attracted audiences of all ranks from 1838 throughout his long career and became Macready’s trademarks. As Paul Schliecke found it, Macready’s close friend Dickens used the material the actor thus provided him with in his novel, The Old Curiosity Shop, to depict the slow tearful deaths of Little Nell and her Grandfather. It was the momentum of an actor and the impetus of a production that re‑established both the Fool and the tragic Lear on British stages, challenging the taste of the contemporary audience, and setting the trend for European and American theatrical practices in the following decades. Macready’s 1838 performance, already shaped by his earlier attempt in 1834, transformed the reading of Lear, a title‑role which he performed successfully until he retired from the stage.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Texte intégral

1Macready’s famous and much acclaimed restoration of Shakespeare’s King Lear in 1838 undoubtedly aspires to the rank of a truly mythical performance. Besides returning to the Shakespearean text, it re‑introduced both the Fool and the tragic ending of Lear to British stages and swept Nahum Tate’s saucy melodrama, The History of King Lear, off the boards for good, thus setting the trend for European and American theatrical practices for the next half of the 19th century. It was, however, not only the textual restoration of the Shakespearean ending and the Shakespearean Fool that made Macready’s production a landmark. It was also the way Macready performed Lear, especially Lear’s death, which was influential enough to prove the actability of the play, thus changing, without doubt for ever, the paradigm for acting and viewing this tragedy.

2However, Jacqueline S. Bratton’s point is valid when she accuses Macready and his followers, Charles Kean and Henry Irving1, of silently allowing « Tate’s rearrangement of the events of the action to shape their supposedly restored text2 ». True, Macready’s promptbooks prove that the end of act 1 and the order of the storm scenes were still more or less maintained as in Tate’s version, although with Shakespeare’s wording, presumably for the sake of convenient scene changes3. Thus, even an enthusiastic Macready researcher must admit that it was not Macready, but the lesser known Samuel Phelps4, who finished the work of the restoration : in 1845 Phelps evened out the order of the storm scenes and made even fewer cuts than Macready, only seven hundred and fifty lines, and had no curtain between the acts.

3Nonetheless, Bratton’s remark does not, by any means, reduce the value or shrink the mythical status of Macready’s revival of the Shakespearean Lear, but it does add an essential detail. As such a retrospective view does not advance the appraisal of Macready’s achievement, my aim is to consider the context from which it developed and its reception at the time. This paper intends to explore the aspects of what was then considered a profoundly unusual representation by looking at Macready’s early promptbook of 1834, besides diary entries and correspondence, as indeed, it is only through such documents that we may understand the motivation behind the cuts and appreciate his interpretation. Macready’s idea of the king, his age, temperament, curses in the storm, relation to the Fool, will be drawn from his relatively unknown 1834 promptbook.

I. Treasuring past productions

4Several 18th and 19th‑century actor‑managers make it into scholarly introductions to Shakespeare’s plays and Macready’s 1838 restoration is often mentioned, for instance in Reginald Foakes’s Arden edition5. However, Macready’s earlier effort hardly ever receives any attention, even though Macready performed a forceful and dynamic, mercurial and brisk, then entirely unknown monarch. This representation attracted audiences of all ranks throughout his long career until his retirement in 1851 and became, just as his restoration, Macready’s trademark. Why is the 1834 production relatively unknown ? The reasons are manifold.

5It seems that documents created in the theatre, witnesses to past productions are perhaps not always appreciated or examined in sufficient detail. « Theatre has to exist in the present, but I sometimes wish », Stanley Wells wrote recently, « it were more willing to treasure its past, and to learn from it. Knowledge of past productions can inform and enrich new ones6 ». In this recent post for the blog of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Wells expressed his gratitude to Arthur Colby Sprague for describing the tradition of stage business in Shakespearean productions in 19457, and Charles H. Shattuck for compiling a register of Shakespearean promptbooks in a catalogue in 19658, as both volumes/collections became the treasure‑troves for later generations of performance researchers. Following Wells’s thread of thought, other King Lear‑pioneers, such as Jacqueline S. Bratton, who recognised the importance of dealing with stage texts, must certainly be mentioned. As early as 1987 she published the stage texts of Lear in a volume and later9, with Christie Carson, made several of the historical promptbooksof King Lear available on a CD‑Rom10, a unique venture of its kind. Moreover, it is through her research that we know of Macready and those producers who more or less followed in Macready’s footsteps. Another of the pioneering researchers who assumed a theatre‑from‑the‑inside point of view is Carol Jones Carlisle : in 1969 she examined some actors’ memoirs and letters to shed light on the historical representations of Shakespearean characters and set Macready’s new Lear in the Betterton tradition11.

6Apart from these Shakespeareans, several Dickensians also paid attention to the 1838 staging of Lear by this great friend of Dickens : as Schlicke wrote in his detailed paper on Dickens and Macready’s Lear12, « the relevance [...] of King Lear to The Old Curiosity Shop is patent13 ». In The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens Schlicke summarises Macready’s influence thus : « Macready’s conception of Lear was shared by Dickens and fed directly into Nell and her Grandfather in The Old Curiosity Shop14. »Clearly, through the talks Dickens and Macready had with their mutual friend, journalist and historian John Forster15, the image of the vigorous and energetic old man who repents over the corpse of his dearest, his sudden and inconsiderate acts fuelled by his rage, provided the novelist with already successful suitable material to depict the slow tearful deaths of Little Nell and her energetic Grandfather. Dickens’s idea of sentimental death was thus tested before the novel in Macready’s 1838 Lear, just as Macready tested Lear at his benefit night in 1834, prior to the complete restoration in 1838.

7Even though Macready’s experimental staging of Lear in 1834 was a success, perhaps because it was given only a few times for his benefit, it was, and still has not been widely publicised. His Diary informs us about the dates and the number of performances : he gave it seven times, three times in London, before going on tour to Richmond, Bristol, Dublin and Bath16. His Diary also mentions his decision to omit the Fool17. We are familiar with the opinions of the theatre critics who penned the reviews for The New Monthly Magazine and The Athenaeum, yet the 1834 production has, to date, remained quite unknown, particularly for theatre historians and Shakespeareans. Dickensians perhaps, purely because of Lear’s relevance in The Old Curiosity Shop18, seem to be more familiar with Macready’s earlier production.

II. 1834 : the Promptbook and the « mighty bone19 »

8Entirely by accident, over a decade ago, I came across the promptbook of this 1834 production in what seems an unlikely location for Shakespearean promptbooks : the Bodleian Library, Oxford20. It is fortunate that the Bodleian holds a copy of the playbill of this production as well. The two can be easily matched and identified as relics of the 1834 production : they both lack the Fool and both feature a character (a Gentleman in Shakespeare) named Locrine, who does not appear in any other production by Macready.

9As our chief concern here is the genesis of what became Macready’s paradigm shifting interpretation, this early prompt copy ought not to be overlooked. Indeed, it must be set among the other, better‑known documents and its most important features must be pointed out so as to see how much of it survived in the famous – or indeed mythical – 1838 production of Lear. Such an examination will provide us with a realistic estimate of how much of Lear, both the role and the play, Macready had in mind as early as 1834, despite the relative silence that surrounds it this first effort/offering21.

10The reason why the production is quite unfamiliar to Shakespeareans is, firstly, because the promptbook has not, till now, been known to exist; secondly, because it is not in Shattuck’s otherwise perfectly reliable Descriptive Catalogue of the Shakespeare promptbooks and, thirdly, because even Macready himself denied the existence of the 1834 restoration in a letter to Lady Pollock in 1864: « You are quite correct in the assertion, that Tate’s King Lear was the only acting copy from the date of its production until the restoration of Shakespeare’s tragedy at Covent Garden in 183822. » However, what Macready has to say here ought not to be taken as a denial of the 1834 experimental performance. At the time, he recorded that the spectators « broke out into loud applauses » in the fourth and fifth acts, and also that « the play was to be repeated on Monday at Covent Garden23 », which was a clear indication of its success. Nonetheless, he did wait for the reviews in the next day’s papers, knowing that « the tone which the Press takes up on it will materially influence my after life24 ». When favourable reception culminated in an invitation to dinner by members of the Garrick Club this hardworking, dissatisfied perfectionist must have felt pampered: « This is really a great and flattering compliment25. »

11Why Macready later denied this utterly successful production can only be surmised or conjectured. Was it a vague and retrospective attempt on the part of such a zealous person to wipe out his erstwhile mistake and reinforce the reception of, and shape the discourse about, his complete and (for him) faultless restoration? What he wrote to Lady Pollock is certainly very subjective. Indeed, besides his own restoration in 1834, it ignores Kean’s three performances in 1820 which blended Tate’s text with the original tragic ending. This is even more surprising when considering the fact that Macready knew Kean’s attempt well, as Kean’s acting copy of the production was once part of Macready’s affluent library26, and he was playing Edmund at the rival theatre, Covent Garden at the time.

12My suspicion is that it was John Forster’s sharp criticism in a review which appeared in the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal may have contributed to Macready’s denial. Perhaps Macready regretted the omission of the Fool, hence his denial in the letter. Apart from what, perhaps, is the better known question in connection with the 1834 production « Ah! Mr. Macready, why did you omit the Fool? », Forster further accuses Macready of having done what no respectful Shakespearean is permitted to do (and what today seems as a basic rule for adapting Shakespeare for the stage): « though you have a right to abridge, you have no right to omit or transpose27 ». Such vehemence as this, taking up over a hundred words, against a friend, is understandable only if one considers, besides Forster’s passionate temperament28, the fact that it was Forster who fathered the idea of Macready producing what had previously been pronounced unactable. Forster demanded the Fool so strongly that he in fact lectured the spectators‑readers, explained the significance of the character and did not mind if, instead of actual theatre criticism, half of the article was devoted to his own interpretation. It was most likely also Forster who, in an another unsigned article, promoted the Fool under the pretext of writing the « Recollections of Kean », that is, of Kean’s vague attempt to retain the tragic ending of King Lear in 1820. The feverish exaltation of the style is characteristic of Forster and perfectly complements the lecture he smuggled into the piece of criticism mentioned:

[If Kean] had really thought of the divine bard’s drama as « the sacred page he was to expound » [Forster quoted Kean’s own words], and not as a means by which he should gain ephemeral applause, he would have insisted on the restoration of every line of that matchless and wonderful tragedy; above all, he would have made it a sine qua non that the part of the Fool should be restored29.

13Forster’s campaign paralleled Macready’s first revival in 1834, apparently aimed at the audience rather than at the actor. No matter how offensive his articles were, however, the commanding tone seemed designed to direct contemporary theatre criticism and contributed largely, through Macready’s productions, to the purging of the adapted Shakespearean texts, as well as to Macready’s complete restoration.

14The only surviving testament to the production apart from the Bodleian promptbook is a threadbare and often chaotic preparation copy of the Macready, now held by the National Art Library in the Forster Collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. As the anonymous Librarian who attached a three‑page typed note to the Bodleian promptbook confirms, « It [the preparation copy at the V&A] records the cuts which Macready made in the text for the production, and its hastily scribbled marginalia relate a few of the actor’s ideas and self‑instructions on the role. But it would be impossible to reconstruct this production [1834] from such a document30. » Shattuck and Bratton, who also devoted some attention to this chaotic copy at the V&A, both agree with the Librarian’s note31. My photographs corroborate Bratton’s and Shattuck’s opinion32.

15Conclusively, no matter how little Macready prided himself upon the 1834 restoration, the sole surviving document, of this fascinating and resolute effort, the promptbook deserves due recognition and attention. The idea of returning to the Shakespearean text of Lear originated in Forster’s essay, which Macready read in January 1834, prompted him to note the following in his Diary : « It has had the effect on me of making me revolve the prudence and practicability of acting the original Lear, which I shall not abandon without serious reflection33. » However, staging the play required a determined effort on Macready’s part. Although Macready was entitled by contract to have his choice of play acted on his benefit night, Alfred Bunn, the manager of both patent theatres, delayed his approval. Bunn’s impertinence left little more than a fortnight for Macready to mount the production [and for the cast to learn their lines]. Nonetheless, the entry for May 4th 1834 in Macready’s Diary makes it clear that the promptbook was ready for use and by then, three weeks before the premiѐre, he had started thinking about and marking the play on May 1st and wrote three days later, that he had finished « the cutting, and then marking fairly the copy of Lear – a task to which I assigned about two hours, which has cost me seven or eight34 ».

16It may come as a surprise how short a period of time he assigned himself for the job being both famous and infamous for his relentless thoroughness and perfectionism and having, as was customary, to cut a passage with a pocket knife and paste it with glue when replacing lines. Had he not already possessed a(n at least roughly) marked preparation or draft copy for his own personal use, he would not have been able to cut and mark the play « fairly » within only seven or eight hours35. Most certainly, he used another copy, possibly the one in the V&A, as a draft, to create a relatively mature vision of Shakespeare’s King Lear in 1834 and which he did not substantially change in 1838.

III. The age and temperament of the king

17Any actor facing the role of Lear is obliged to make a number of crucial decisions relating to his impersonation. The age and temperament of the king, the staging of the storm and the issue of his Fool pose the most fundamental and also unavoidable, as well as strongly interrelated questions the actor must answer. The representation of the king’s age, his relation to his Fool and the storm all determine the actor’s overall credibility in the role and his ultimate success. The on‑stage storm cannot be left merely, as a kind of impressive spectacle, to the stage‑manager’s wind‑machine: Lear’s character must always be proportional to it. Interestingly enough, already in 1834 Macready appears to have designed the key aspects of his role with the utmost care; in what follows, I will pick a few of the several examples in his 1834 prompt copy.

18It was Carol Jones Carlisle who found that the issue of physical and mental decay marks a real watershed in the portrayal of Lear, distinguishing two very different acting traditions : that initiated by Garrick and then Kean – what I call the « infirm » tradition –, the other, by Betterton, to which Macready returned. The old man who is feeble (either hysterical or gentle) from the beginning, was performed by Garrick, Edmund Kean and Henry Irving, promoted by William Hazlitt and criticised by Charles Lamb. Lamb famously wrote in 1811 that « to see Lear acted, [...] has nothing in it but what is painful and disgusting36 ». His idea radically differs from the noisy, brisk and firm monarch whose lasting rage gradually subsides towards the end of the drama. Lamb must have seen the weak Lear in Edmund Kean’s 1820 performance, concluding that « the Lear of Shakespeare cannot be acted » and that it was pitiful to see Lear « tottering about the stage with a walking stick37 ». Prompted perhaps by Lamb’s criticism, Macready consciously and clearly wanted to prove the theatricality and actability of Lear. Macready actually used Lamb’s word « tottering » in his comment on Kean’s impersonation of Lear in his Reminiscences dated 1855, which is indeed telling, and I cannot but take it for granted that he had in mind an antithesis : « The power of such vast imaginings would seem incompatible with a tottering, trembling frame38 ». It is even more unusual, at least with regard to his predecessors’ Lears, that he did not aim at continuous pathos and elevation throughout the role. He further adds that in Lear’s figure « [t]here is, moreover, a heartiness, and even jollity in his blither moments, no way akin to the helplessness of senility39 ».

19Was Macready of the same opinion in 1834 ? Most certainly, he was. There is an entry in his Diary, not recorded in his Reminiscences, which briefly refers to the fact that he was indeed concerned with the age‑problem and Lear’s feebleness and that what he produced was not the norm for a spectator in the mid‑1830s. Touring with this first, Fool‑less Lear in Bath, January 17th, 1835, he wrote : « Saw Dowton at rehearsal, who complimented me on Lear, and gave me to understand that my assumption of age was good, which much pleased me40 ». On the day following the première he wrote, « I threw away nothing ; took time, and yet gave force to all that I had to ; above all, my tears were not those of a woman or a driveller, they really stained a ‘man’s cheeks’41 ». Indeed, the portrayal of manliness and strength was the keynotes of his interpretation. Relying on Forster’s 1838 theatre criticism, Bratton, though not an enthusiastic Macready fan herself, arrives at a similar conclusion when summarising Macready’s Lear : « Macready showed Lear to be in need of consideration and pity for his incapacity to control himself and his temper » from the very beginning of the performance, rather than an infirm and woeful oldster42.

20The first sign of this choleric and masculine attitude is seen at the first clash between Kent and Lear in act 1. The minute detail of the promptbook (page 6) justifies what Macready wrote in his Diary : « Kent is to Lear the most important personage in the play...43 ». The text of the 1834 production, « accurately printed from the text of Mr Steevens’s last edition44 », instructs Lear to « lay his hand on his sword » at the cue « O vassal ! miscreant45 ! ». However, in his promptbook, Macready’s handwritten instruction « Seizing his sword from Officer R. [Officer on his right] », requires a much more menacing action, such that the two younger men on the king’s sides, « Albany, R. – Cornwall, L. must take hold of him ». This stage business survived into the impressive 1838 production, and was copied by later actors such as Charles Kean, Samuel Phelps, Henry Irving or Randle Ayrton46. Macready clearly made efforts, not only in his mature performances in the late 1840s, but from the very first night, to depart from the « infirm » tradition and create an energetic, horse‑riding, big‑hearted old fellow for Lear.

21Another instance of Macready’s choice of an impetuous and agile Lear in 1834 is to be found in act 2, scene 4 : here as well, Macready took great care to omit any the references to weakness or infirmity from Lear’s speech :

[...]

Infirmity doth still neglect all office,

Whereto our health is bound ; we are not ourselves ;

When nature’s being oppress’d ; commands the mind

To suffer with the body. I’ll forbear ;

And am fallen out with my more headier will [...]

(Promptbook, p. 6).4

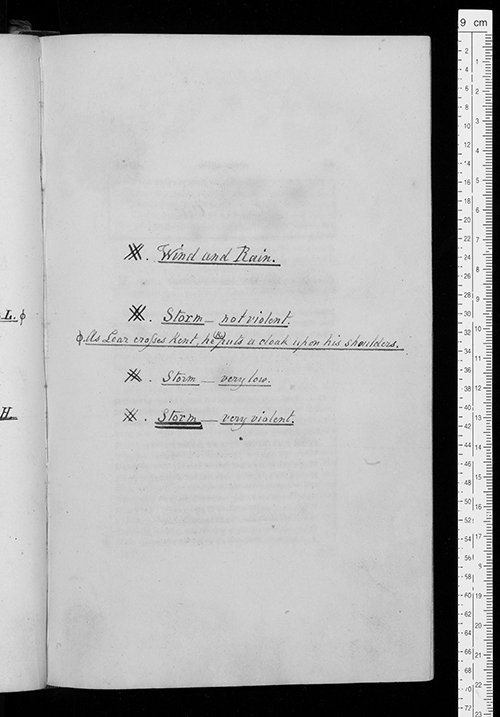

IV. The Storm

22The assumption that, throughout his career, Macready acted along certain guidelines he had elaborated for himself while marking his prompt copy in the spring of 1834 seems to apply to his representation of the storm as well. Several pages from the promptbook demonstrate that, unlike Edmund Kean, who was won over by de Loutherbourg’s Eudophusikon, Macready by no means let himself be dwarfed by the harrowing noises of the wind‑ and rain‑machines. Contrarily, employing a great deal of what we would call these days a close reading, he made good use of these instruments to achieve maximum effect. The promptbook displays a text that runs smoothly throughout, without any famous points for the star but not without minute responses to the elements or the other characters.

23Bratton accuses Macready of boasting that his 1838 text was purely Shakespearean although his arrangement of the storm scenes resembles Tate’s scene order. Perhaps this is just the partiality natural to a Macready researcher, but I believe that Bratton is being somewhat unjust. We must take into consideration contemporary stage facilities : the groove‑system, as well as the depth and the size of the stage. The most knowledgeable scholar concerning the shutter‑and‑groove system, Richard Southern, wrote in his Victorian Theatre : A Pictorial Survey that even if the change of scenes offered a spectacle for the early 19th century audience, « the falling into position of the hinged groove extensions after a set scene, […] the closing of the flats, produced a violent thud with the clanking of the chains that checked them47 ». Thus quite unsurprisingly, and as Tate had done before him, Macready reduced the number of scenes shifting to just as few as the plot allowed, for the violent thuds and the clanking of the chains would have evidently spoiled the illusion or magic created by the actors in the heath scenes. Shakespeare’s swift scene changes are either suitable for a barren stage, such as the Elizabethan one now seen at the New Globe, for Peter Brook’s empty space, or for films. The weight, the noise and the disturbingly slow pace of moving the heavy Victorian flats and wings offer a perfectly justifiable explanation for why the actual changes Macready made to the storm scenes in 1838 were so infinitesimal in terms of the technical details he had planned48, carefully designed and already tested in 1834. Indeed, his instructions related to location and scenery are the same in both 1834 and 1838.

24The cuts in the promptbook illustrate the way Macready used the heavy groove‑system to his advantage. For instance, act 2, scene 2 takes place at the Gates before Gloster’s Castle in the fourth grooves, and it is here that Kent is put into the stocks ; it is here also that act 2, scene 4 continues with the discovery of Kent, while the scene in between, featuring another thread of the plot, namely Edgar’s monologue, uses the first grooves to depict the heath. The wings in the first grooves were simply closed on Kent, who stayed where he was, and re‑opened on him at the end of Edgar’s speech (pages 36, 42, 43). Thus, contrary to Bratton’s conclusion, I argue that Macready did liberate the Shakespearean text from Tate’s « disfigurement », but was, as the crafty man of the theatre he was, unwilling to sacrifice the momentum and the focus of the performance to some purely cultic, theoretical, and un‑theatrical achievement.

V. The Fool

25With a complete restoration in mind from the very beginning, Macready eventually omitted the Fool from the 1834 production. He was fully aware of the change of paradigm he was dictating and the change of public taste he was initiating, and thought, without illusions, that including a comic character in the freshly established tragic King Lear was too drastic a change. Tate’s text, which Macready called the « miserable debilitation and disfigurement of Shakespeare’s sublime tragedy49 », held the stage firmly for a hundred and fifty‑three years, from 1681 to 1834, and proved to be such a powerful adversary that it could not be easily erased from the stage and page, in short, from cultural and theatrical memory. « My opinion of the introduction of the Fool is that, like many such terrible contrasts in poetry and painting, in acting representation it will fail in effect ; it will either weary and annoy or distract the spectator. I have no hope of it, and think that at the last we shall be obliged to dispense with it50 », Macready wrote just a few weeks before the complete 1838 restoration suggesting the Fool was to be omitted again. He was worried the Fool might distract the spectators, an argument that fits into the picture the 1834 promptbook conveys of him : the creator, on both page and stage, of momentous performances, who designs and subordinates every detail so as to serve an ultimate, single purpose, that is, the effect of the show (worthy of Shakespeare’s magnificent drama). Distraction seemed to be the argument against the inclusion of the Fool in 1834, and the elimination of the supposed distraction allowed him back on the boards in 1838.

26We are mistaken, however, if we assume that Macready gave up the idea of the Fool in 1834, as, for one the Fool’s role is spelled out clearly in the cast of the promptbook. Not only do we find references (p. 19‑20), stage instructions (p. 61) to the Fool in the promptbook, but entire printed lines for him remain in the text (p. 64) or are even wedged in in longhand. Elsewhere, for instance, a page‑long handwritten section features the Fool immersed in a dialogue with his master (p. 21).

27The comparison of the scripts of the two performances proves that, in fact, Macready made very little adjustment to his 1834 text when he re‑inserted the Fool in 183851. The character that made its stage debut in 1838 was a somewhat feminine creature, a singing young boy, and was meant to enrich Lear’s characterisation with gentle, poetic touches52. Interestingly enough, the Fool’s character did not substantially change the image of Lear Macready had in mind, a fact that also supports the assumption that Macready was indeed on the verge of risking a complete restoration in 1834 (and was on the verge of dispensing with the Fool in 1838).

28The only explanation for his not daring to put the Fool on stage was the half‑century‑old tradition of respecting and fearing the viewers’ reactions. Numerous anecdotes, drawings, caricatures of the time and even contemporary plays eternalise the dictatorial conduct of the late 18th century theatregoers, doing anything for the sake (or taste) of scandal, from ripping cushions off from seats, or throwing hard objects at the performers to dropping lumps of cheese onto the pit from the balcony. The O. P. (Old Price) Riots which lasted nearly three months in 1809, embittering John Philip Kemble’s life and management, were not a thing of the past for Macready in 1834. In her Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan Tiffany Stern devotes several pages to the often atrocious behaviour of the audience (unimaginable today) and concludes that « [p]lays were thus shaped not only by the way actors learnt their lines, but by the anticipation of the way the audience might respond » and that « [t]he system of immediate audience approval or condemnation expressed with claps and hisses demanded direct response53 ». Hence, it is easy to understand why, after the premiѐre, Macready was not certain of the effect he had produced and why he feared the press so much, because it aired and dramatically influenced the response of the spectators at once : « I felt the excitement [...] of what seems success, but I must wait until to‑morrow to know with certainty the impression I have produced. [...] [T]he tone which the Press takes up on it will materially influence my life. [...] Attendez ; nous verrons », he wrote in his Diary54. Writing about Macready as Benedick a decade later, Charles Dickens « defended the actor’s right to challenge an audience’s preconceptions55 ». The mere fact that this was necessary as late as in 1843 betrays the power of the audience in Macready’s time and also the risk Macready was taking at his benefit night in 1834. He was not exaggerating when he wrote in his Diary that his entire career, reputation and pay – meaning a middle‑class lifestyle for his large household – were at stake with such a daring performance.

Conclusion

29As the evidence shows, whatever Macready proceeded to do on the stage or on the page in 1838 was founded on his 1834 experiment. Macready’s overall opinion of Shakespeare’s Lear from the point of view of its actability as well as the temperament of its eponymous hero (first vigorous, and then much calmer) proved successful in 1838 and became the norm for the rest of the 19th century. It set the example for Samuel Phelps, Charles Kean and Henry Irving and even Charles Dickens ; and, as I have argued, was sketched out in the 1834 production and its promptbook.

30In the 1834 promptbook « [e]xtensive stage business, music cues, calls, grooves, full orchestration of effects in heath scene, and map for the final tableau are all recorded in considerable detail56 ». We must, however, bear in mind Sprague’s warning that « [e]ven promptbooks are not infallible guides to what actually happens on stage57 ». Nonetheless, the layers of stage directions, stage business, hesitations, various handwritings, make this, as the Librarian also attested, « a fine example of a nineteenth century promptbook58 », which, with little overstatement, challenged the prevailing opinion of the adapted and also challenged the prevailing opinion of the tragic King Lear.

31Admittedly though, Macready’s return to the original text and his staging pervaded with psychological realism would not have attained its cultic status without the effective assistance of (friends in) the press. Induced by John Forster, myth‑making around the revival was already under way in 1834, and merely intensified four years later. Hence my proposal that at least a fraction of the fame or myth surrounding Macready’s celebrated restoration of the Shakespearean Lear in 1838 be conferred to his earlier staging of the play in 1834.

Bibliographie

Bate, Jonathan, The Romantics on Shakespeare, London, Penguin, 1992.

Bratton, J. S., King Lear (Plays in Performance), Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1987.

Bratton, J. S., « The Lear of Private Life : Interpretations of King Lear in the Nineteenth Century », in Richard Foulkes (ed.), Shakespeare and the Victorian Stage,Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 124‑137.

Bratton, J. S. and Christie Carson (eds.), The Cambridge King Lear CD‑Rom : Text and Performance Archive, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Carlisle, Carol Jones, Shakespeare from the Greenroom. Actors’ Criticisms of Four Major Tragedies, NC : Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Carlton, William J., « Dickens or Forster ? Some King Lear Criticisms Re‑examined », Dickensian, 61 (1965) p. 133‑140.

Dávidházi, Péter, « Redefining knowledge : An epistemological shift in Shakespeare studies », Shakespeare Survey, 66 (2013) p. 166‑176.

Forster, John, « Recollections of Kean », The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, 2 (May, 1834), p. 220‑221.

_______________ The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, 41 (May, 1834), p. 59.

Gager, Valerie L., Shakespeare and Dickens. The Dynamics of Influence, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Ioppolo, Grace, William Shakespeare’s King Lear : A Sourcebook, London, Routledge, 2003.

Lamb, Charles, « On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, considered with reference to their fitness for stage representation », in Charles W. Eliot (ed.), English Essays : Sidney to Macaulay, vol. 27, New York, P.F. Collier & Son, 1909‑1914.

Macready, William Charles, William Charles Macready’s Reminiscences and Selections from his Diaries and letters, Frederick Pollock (ed.), London, Macmillan, 1875.

Reuss, Gabriella, « Viharos sikerek, sikeres viharok : a vígvégű és a tragikus Lear király szín‑változásai » in István Géher and Attila Atilla Kiss (eds.), Az értelmezés rejtett terei. Shakespeare‑tanulmányok, Budapest, Kijárat Kiadó, 2003, p. 129‑142.

_______________, « King Lear, 1834 », Diss., Budapest, ELTE, 2003.

_______________, « Veritas Filia Temporis, or Shakespeare Unveiled ? Macready’s 1834 Restoration of Shakespeare’s King Lear », The AnaChronisT, 6 (2000), p. 88‑101.

Schlicke, Paul, « A ‘Discipline of Feeling’ : Macready’s Lear and The Old Curiosity Shop », Dickensian, 76 (1980), p. 79‑91.

Schlicke, Paul (ed.), The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Shakespeare, William, King Lear, R. A. Foakes (ed.), London, Arden, 1997.

_______________ King Lear, J. S. Bratton (ed.), Bristol Classical Press, 1987.

Shattuck, Charles H., The Shakespeare Promptbooks, A Descriptive Catalogue, Urbana and London, University of Illinois Press, 1965.

_______________ (ed.), William Charles Macready’s King John. A facsimile prompt‑book, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1962.

Southern, Richard, The Victorian Theatre : a Pictorial Survey, Newton Abbot, David and Charles, 1970.

Sprague, A. C., Shakespeare and the Actors. The Stage Business in his Plays (1660‑1905), MA : Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1944.

Stern, Tiffany, Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Toynbee, William (ed.), The Diaries of Macready, London, Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Wall, Stephen (ed.), Charles Dickens, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1970.

Wells, Stanley, « The Stage and the Scholars », BloggingShakespeare.com, 2 May 2013, Web, Accessed 27 February 2015.

Notes

1 Charles Kean used Macready’s promptbook and Irving followed it with a few line differences. We know from Charles Shattuck that Kean in fact paid G. C Ellis, a former assistant to Macready’s chief prompter Wilmott, to transcribe Macready’s promptbook for him. See Charles H. Shattuck (ed.), William Charles Macready’s King John. A facsimile prompt‑book, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1962, p. 5.

2 Jacqueline S. Bratton, King Lear (Plays in Performance), Bristol, Bristol Classical Press, 1987, p. 130. Italics are mine.

3 Further details on scene changes and the consequences of the heavy Victorian stage machinery in Gabriella Reuss, « Viharos sikerek, sikeres viharok : a vígvégű és a tragikus Lear király szín‑változásai » in István Géher and Attila Atilla Kiss (eds.), Az értelmezés rejtett terei. Shakespeare‑tanulmányok, Budapest, Kijárat Kiadó, 2003, p. 129‑142.

4 Samuel Phelps was a former member of Macready’s select Covent Garden Company and later manager of Sadler’s Wells.

5 William Shakespeare, King Lear, R. A. Foakes (ed.), London, Arden, 1997.

6 Blog post dated May 2nd 2013. http://bloggingshakespeare.com/the‑stage‑and‑the‑scholars.

7 Arthur C. Sprague, Shakespeare and the Actors. The Stage Business in his Plays (1660‑1905), MA : Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1944.

8 Charles H. Shattuck, The Shakespeare Promptbooks, A Descriptive Catalogue, Urbana and London, University of Illinois Press, 1965.

9 William Shakespeare,King Lear, J. S. Bratton (ed.), Bristol Classical Press, 1987.

10 J. S. Bratton and Christie Carson (eds.), The Cambridge King Lear CD‑Rom : Text and Performance Archive, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

11 Carol Jones Carlisle, Shakespeare from the Greenroom. Actors’ Criticisms of Four Major Tragedies, NC : Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

12 Schlicke’s analysis is so far « the only one based on Macready’s promptbook », remarked Valerie L. Gager in Shakespeare and Dickens. The Dynamics of Influence, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 14.

13 Paul Schlicke, « A “Discipline of Feeling” : Macready’s Lear and The Old Curiosity Shop », Dickensian, 76 (1980), p. 81.

14 Paul Schlicke (ed.), The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 368.

15 See Dickens’s letter written to Forster on January 17th, 1841 : « After you left last night, I took my desk upstairs ; and writing until four o’Clock this morning, finished the old story ». In Charles Dickens, Stephen Wall (ed.), Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1970, p. 54.

16 Performancesin 1834 : May 23rd, Drury Lane Theatre ; May 26th, Covent Garden Theatre ; June 2nd, Covent Garden Theatre, London ; August 29th, Richmond ; September 13rd, Bristol ; November 17th Dublin, and January 17th 1835, Bath.

17 In William Shakespeare’s King Lear : A Sourcebook, London, Routledge, 2003, Grace Ioppolo mentions the production referring to and quoting from Macready’s Reminiscences and Diary (entry dated May 23rd 1834), p. 69, 80.

18 William J. Carlton, « Dickens or Forster ? Some King Lear Criticisms Re‑examined », Dickensian, 61 (1965) p. 133‑140.

19 William Charles Macready, William Charles Macready’s Reminiscences and Selections from his Diaries and letters, Frederick Pollock (ed.), London, Macmillan, 1875, p. 207.

20 Gabriella Reuss, « Veritas Filia Temporis, or Shakespeare Unveiled ? Macready’s 1834 Restoration of Shakespeare’s King Lear », The AnaChronisT, 6 (2000), p. 88‑101 ; and also Gabriella Reuss, « King Lear, 1834 », Diss., Budapest, ELTE, 2003.

21 « [S]peculation is back again », Péter Dávidházi notices in his « Redefining knowledge : An epistemological shift in Shakespeare studies », Shakespeare Survey, 66 (2013)p. 166, an essay which concludes : « Working with a precise methodological rationale of the probable would suit our new age of the virtual far better than the old reliance on an allegedly exclusive certainty of the tangible », p. 176.

22 Letter to Mrs. Pollock, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., 462.

23 Diary entry for May 23rd, 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 140.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid., p. 144.

26 Now held in the Forster Collection of the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

27 John Forster, « Recollections of Kean », The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, 2 (May, 1834), p. 220‑221. Forster mentions the « absolute power of ordering what restorations you pleased on the late occasion » which is and has always been granted to a director.

28 When once Forster attended a dinner at the Garrick Club without being invited Macready mercilessly remarked of his friend : « He is very indiscreet », in his Diary, May 29th 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit.

29 John Forster, The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, 41 (May, 1834), p. 59.

30 Librarian’s note, a typed three‑page note placed in Macready’s 1834 promptbook in the Bodleian Library, p. 2.

31 Shattuck describes it as « a study book or preparation copy », and not a promptbook, « heavily cut, the Fool deleted » with « Many curious marginalia, some in Latin and Greek », op. cit., p. 211, and of which J. S. Bratton said nearly the same in « The Lear of Private Life : Interpretations of King Lear in the Nineteenth Century », in Richard Foulkes (ed.), Shakespeare and the Victorian Stage,Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 128.

32 My photographs were taken at the National Art Library in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London thanks to a generous grant, the Anthony Denning Award from the Society for Theatre Research in 2000.

33 Macready’s Diary, entry for January 26th 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 97. Italics are mine.

34 Macready’s Diary, entry for May 4th 1834, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 130.

35 Macready may have started the marking a day earlier, on May 3rd 1834, on the day of his accepting the benefit night, but it is unclear whether it was the « fair copy » or not. His diary reads : « Sat down to proceed with Lear, of which I marked a great deal », entry of May 3rd 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 130.

36 Charles Lamb, « On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, considered with reference to their fitness for stage representation », in Charles W. Eliot (ed.), English Essays : Sidney to Macaulay, vol. 27, New York, P.F. Collier & Son, 1909‑1914, p. 18.

37 Ibid.

38 Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 207. Macready started to write up his diary entries when he retired in 1851. Italics are mine.

39 Ibid, vol. 1, p. 207. Italics are mine.

40 In Macready’s Reminiscences, dated January 19th 1835, vol. 1, p. 447, which, for some reason, is missing from Macready’s diary.

41 Macready’s Diary, entry for May 26th 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences op. cit., vol. 1, p. 143. This performance, given at Covent Garden, was the one that was scheduled instantly (and unexpectedly) by Bunn in view of the first night’s success. Italics are mine.

42 Jacqueline S. Bratton, King Lear..., op. cit., p. 73.

43 Macready’s Diary, entry for June 2nd 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences op. cit., vol. 1, p. 146.

44 See the inside cover page of Macready’s 1834 promptbook.

45 Printed stage instructions are italicised.

46 Jacqueline S. Bratton, King Lear..., op. cit., p. 73.

47 Richard Southern, The Victorian Theatre : a Pictorial Survey, Newton Abbot, David and Charles, 1970, p. 30.

48 Despite the fact that the building of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was modernised in 1812 and again in the following decades.

49 Charles Macready’s Reminiscences, 1, p. 205.

50 Macready’s diary, dated January 4th 1838, in Macready’s Reminiscences, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 437.

51 For Macready’s 1838 cuts and stage business I relied on J. S. Bratton’s promptbook study edition of King Lear, op. cit.

52 Macready had the part played by a nineteen year‑old actress, Miss Priscilla Horton.

53 Tiffany Stern, Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 280, 277.

54 Macready’s diary, entry for May 23rd 1834, in Macready’s Reminiscences op. cit., vol. 1, p. 141.

55 Charles Dickens’s review « Macready as Benedick » appeared in The Examiner, 12 March 1843, mentioned by Paul Schlicke, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 368.

56 The Librarian’s note, p. 1.

57 A. C. Sprague Shakespeare and the Actors. The Stage Business in his Plays (1660‑1905), MA : Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1944, p. 297.

58 The Librarian’s note, p. 3.