- Accueil

- > L’Oeil du Spectateur

- > N°4 — Saison 2011-2012

- > Adaptations scéniques

- > A lightning before death: Olivier Py’s staging of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

A lightning before death: Olivier Py’s staging of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

At l’Odéon, Théâtre de l’Europe (Paris, from the 21st September to the 29th October 2011).

Par Stéphanie Mercier

Publication en ligne le 14 novembre 2011

Texte intégral

1Olivier Py’s 2011 adaptation of Shakespeare’s circa 1596 play is summed up on the Odéon Theatre’s website1 as: “A lightning before death” (III.5.90)2, a common phrase for the phenomena of life literally flashing before one’s eyes just before the onslaught of death. Metaphorically, the expression also conveniently sums up the stage director’s craft: that is, the dramatic exposure of the playwright’s text for the limited time and space of the play before the curtain’s final fall. In this 21st century interpretation of a 16th century text, Py purports that Romeo and Juliet’s mutual attraction occurs, not despite of the feuding Montague and Capulet families’ hatred, but precisely because of this3. In other words, the paradox of Romeo and Juliet’s self destructive love is an instrument of rebellion against family and societal hegemony and not, as is usually held, the sacrifice of naïve and innocent children at the hands of their cynically cruel parents.

2In this paper I will thus be examining how Py acts out his role as puppet master, or as Vladimir Nabokov would have it, an “anthropomorphic deity4” impersonated by his maker, up in the Gods as it were and looking down upon the theatre of Shakespeare’s action. To do so, I will first examine how Py has the lovers play with fire and how this soon turns into the instrument of their own tragic imprisonment. I will then move on to look at how being caught at playing dead can ironically be the means to a theatrical liberation. Finally, and if the lovers are seen to escape into the fictional eternity of Py’s universe, how this can only be for the space of the dramatic representation of the playwright’s text5.

Playing with fire

3Py’s Romeo and Juliet is a play about younger generation Montagues and Capulets who have grown up amidst feuding and bloodshed. The two children are then both utterly opposed due to their family differences but at the same time similar in the fact that they seem aware of, though totally impervious to, the dangers of love and death. This idea is presented visually in the very first appearance of the two characters when a silent Juliet appears upon a mobile scaffold whilst Romeo expounds Rosaline’s beautybelow (I.1.226-235). Juliet’s first appearance as a voiced participant to the action is as a petulant and irresponsible child who is seen placing a pistol to her forehead in an act of mock suicide as the nurse is repeatedly heard gibbering, something which metaphorically and almost literally bores the young girl to death (I.3.17-48). This immediately gives spectators the impression that love is to be dangerously gagged and vociferous and the same time indivisible and polymorphous throughout the play.

© Alain Fonteray. Camille Cobbi as Juliet.

4The multiplicity also means that the children are seen to be a product of and interchangeable with their elders (Juliet’s surrogate mother, the Nurse, is a personified oxymoron: dressed as the strictest of English governesses whilst proffering swear words and liberally helping herself to a hip flask at the slightest excuse) and their peers (Romeo’s fatheronly appears at the beginning and end of the play (I.1 and V.3) and so his parenting is left to Mercutio and Benvolio; who are prone to bawdy puns and physical exhibitionism when they are not involved in street fighting). The lovers cannot rival with nor escape from the disparaging brutality of the games played by those around them and Py is pointing towards the fact that their tragic plunge towards death is their only possible act of revolt. In other words, their impossible love is the positive charge in response to that of the negativity of their parents’ hatred – or the lightning before the final thunderclap of death.

© Alain Fonteray. Camille Cobbi as Juliet, Matthieu Dessertine as Romeo and Philippe Girard as Friar Laurence.

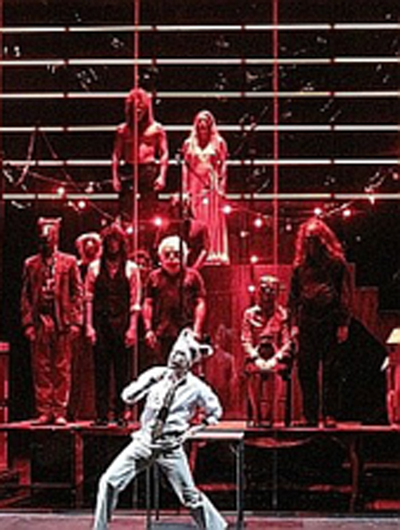

5In this, theirs is an inherited tragedy, one of filiations and affiliation – a logical offshoot of the codes that they find themselves imprisoned within. Romeo is seen to roam the Veronese streets but his theatrical existence is just as closed in as that of Juliet who only leaves the microcosmic confines of her family home to enter the macrocosmic restrictions of Friar Laurence’s cell6. Indeed Py’s pointed emphasis on verticality (scaffolding) and horizontality (the neon bars shown in the photo here) create a visual criss-crossing which suggests the prison of Veronese society and culminates in the ultimate intersection of the Christian cross when the lovers are finally imprisoned in death.

Playing dead

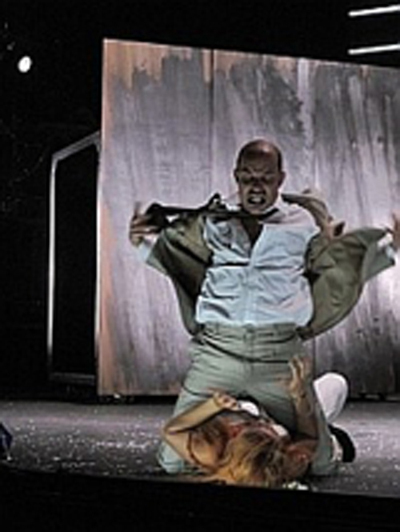

6Before the play’s reversal of fortunes and its tragic close however, the actors indulge in what may seem as a rehearsal of dying – or the Elizabethan paradigm of a play within a play – as Juliet plays at being unmarried and then at being dead as she takes Friar Laurence’s vial (IV.3.58), this in a passionate attempt to escape the inevitable.

© Alain Fonteray. Camille Cobbi as Juliet, Olivier Balazuc as Capulet

7However, if it is passion that compels Juliet to take Friar Laurence’s potion, it is a passion to be taken on an etymological level, coming from the ancient Greek and meaning to suffer or endure. Passion is also the state or emotion when being acted upon by external agents or forces and the common noun has also come to be associated with the Passion of Christ, or His sufferings during the period between the Last Supper and Crucifixion. All of these definitions are combined in the sadism with which Capulet compels his daughter to marry Paris and the violence of Juliet’s reaction; especially as Py has Olivier Balazuc play both father and County Paris, the lover, so adding incestuousovertones to the father-daughter relationship and thus reinforcing the brutality of the match.

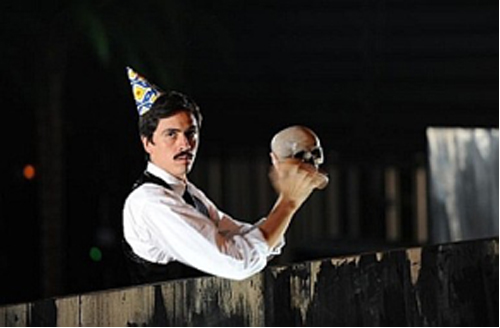

8Indeed throughout the play Py renders counterpart what should have been counterpoint. Apart from the father-son (in-law) duo of Capulet-Paris, family ties are further distorted as Quentin Faure, who plays Tybalt or Juliet’s cousin, also becomes Juliet’s mother by wearing a black veil through which he/she chain smokes and bites his/her nails instead of intervening during Capulet’s mistreatment of Juliet. This transgression, or crossing over, of family and gender lines, shows how social order hides a dangerous moral disorder in Veronese society. Probably the best example of this in the play is the doubling of Prince and pauper (see legend), or a whole range of subordinates, as Py underlines the perversion of societal as well as family codes in the plot.

© Alain Fonteray. Barthélémy Meridjen plays the Prince, the Clown, the Chorus, the Apothecary, Gregory and Friar John – in other words all levels: high/low, spiritual/secular… of society – and theatre: mimetic/diegetic.

9In such a society it is hardly surprising that the traditional counterpoints of Eros and Thanatos become counterpart and the remaining characters are metaphorically and literally covered with ashes by the final scene of the play. The irreverent Nurse throws these ashes upwards in a gesture reminiscent of that of throwing confetti at a wedding whilst the confetti present on stage since Romeo and Juliet’s first meetingremains resolutely inert. Symbolism and characterisation allow Py to upturn traditional values, thus liberating our preconceived ideas about Shakespeare’s manuscript. Paradoxically this also allows for its dramatic eternity as the lovers are only playing dead and their theatrical multiplicity means that the text can have them metamorphose into yet other forms7.

Playing at God

10This perpetual recreation is made possible then from within and without the text and the obvious nod at Hamlet8 in the last photograph, used to drive home the point about the evanescence of life, is not the only intertextual reminder in the production. The summarily stage propped (the mobile grey scaffolding, a red screen to separate theatrical space and the plastic palm trees) and starkly costumed play is ironically very richly layered with extradiegetic material. This is to further emphasise the power of the stage and more widely art, a point put forward by a director whose ultimate goal is in fact to encourage us to strip away the layers in order to get back to the basics of the text itself.

© Alain Fonteray. In the foreground, Olivier Balazuc as Capulet. In the background Camille Cobbi as Juliet and Quentin Faure as Tybalt: «Prince of cats» (II.4.19).

11Intertextuality also includes cinema in the production. The film noir genre is omnipresent with its shadows, sordid setting, firearms and foreboding background music, sometimes played by the characters themselves (Juliet and Tybalt). Throughout the plot we see a silent onstage pianist, first hidden in military camouflage and then allowed to take an increasingly prominent role in the action, change costume and finally be given speech as he plays the part of the second musician (IV.5). Py plays on our senses, combining musical and cinematographic references at one point by his use of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto N° 2 in C minor which was also played by Eileen Joyce in the 1945 British film Brief Encounter9, itself based on a 1936 stage play, Still life, by Noël Coward. Even if this kind of reference is almost to be expected on a stage featuring an omnipresent dressing mirror typical of 20th Century Hollywood, Py’s production shies away from the clichés of the pantomime genre whilst at the same time encouraging his audience to mentally participate in an extremely interactive manner in order to construct their own particular response to the play.

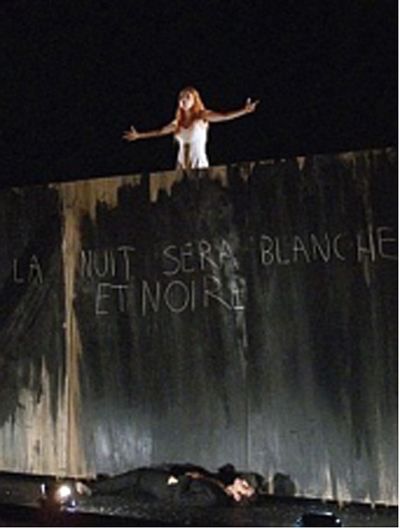

12The dressing mirror is also a symbolic reminder of the prison of fiction that the actors are trapped in for the space of the staging of the text. Just before the interlude Romeo writes: « La nuit sera blanche et noire10 » upon the slate coloured scenery. Later, in what we imagine to be Friar Laurence’s cell, the Nurse wipes away the text to the exception of the «O» 11 whilst Romeo sticks a pistol in the cavity of his mouth. The «O», or black hole of nothingness (the ultimate emblem of the zero truth of fictional staged reality) is transformed at the end of the play however because it is also used as part of the sentence: « La mort n’existe pas » which debunks this very void of fiction. Fittingly Romeo writes rather than speaks this on the scenery as a parting gesture in what would seem to be Py’s ultimate personal commentary on both his art and Shakespeare’s text – a perpetual coming and going between stage death and textual eternity. The characters are turned into statues, just as inert at Shakespeare’s text, but are ready at any moment to be brought to life again12.

13In this version of Romeo and Juliet then, we see actors playing games in order to break the rules with Olivier Py as an arbitrator between us and Shakespeare’s text. His play means that the text is concealed within its staging and temporarily cancelled by the final curtain call when the actors leave the stage. However, if the final potential tragedy for a writer and stage director is that of the evanescence of theatrical representation, I have shown here that Py works not despite but because of this. So I will conclude by reiterating that just as Romeo and Juliet are caught in and liberated by their rebellion, so Py throws out Shakespeare’s line(s) to the audience as it were in order to haul us into the fiction and be unable to do anything else but look at the text under a new light. This is the very « lightning before death » that Romeo mentions before his demise and the play’s close. Indeed Py is inviting us to re-read Shakespeare’s text and thus continually throw new light upon it – just as Romeo makes it clear as he silently chalks onto the blackboard scaffold of the balcony: « La nuit sera blanche et noire13 ».

© Alain Fonteray. Camille Cobbi as Juliet and Matthieu Dessertine as Romeo.

Notes

1 http://www.theatre-odeon.fr/

2 William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, ed. Alfred Harbage, London, Penguin Books, The Complete Pelican Shakespeare, 1981. The translation used for this production is Py’s own. His very modern translation is unpublished but extracts are to be found in the Theatre’s website resources (http://www.theatre-odeon.fr) and is based on Roméo et Juliette, traduction Pierre Jean Jouve et Georges Pitoëff, présentation par Harley Granville-Barker, Paris, Flammarion, 2011, Roméo et Juliette, Shakespeare, préface et traduction Yves Bonnefoy, Paris, Gallimard, 2001, Roméo et Juliette, traduction de François Victor Hugo, texte et dossier, lecture accompagnée par S. Jopeck, et Pierre Notte, Paris, Gallimard, in William Shakespeare, Oeuvres complètes, édition bilingue, tragédies 1, Paris, Robert Lafont, 2001.

3 http://www.theatre-odeon.fr/

4 Leona Toker, The Mystery of Literary Structures, New York, Cornell University Press, 1989, p. 195.

5 Anne Ubersfeld, Reading Theatre, Toronto, University of Toronto Press Incorporated, 1999, “Chapter 1: Text Performance, The Performance-Text Relation”, p. 3.

6 “My concealed lady to our cancelled love?” (III.3.98). Romeo’s concealed (hidden from me)/cancelled (invalidated) were given almost the same pronunciation to highlight their similarity of meaning in the original text and the French production renders this scenically as the characters never escape the artificially lit interior of the stage until their deaths.

7 The lovers are to be transformed into golden statues. See V.3. 299-304.

8 Another tragedy which can be interpreted as one of seclusion and isolation. William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, ed. Alfred Harbage, William Shakespeare, London, Penguin Books, London, The Complete Pelican Shakespeare, 1981, V.1.71-127.

9 Brief Encounter could be a very appropriate 21st Century subtitle for the play. The film, starring Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, is concerned with a suburban housewife frustrated by the polite arrangement of her marriage and the passionate emotions that real love provokes in her. The end is also tragic as the platonic lovers are parted forever but Johnson returns to her dreary husband after conquering her impulse to commit suicide.

10 The interlude takes place just after Mercutio’s death and just before that of Tybalt (III.3.118). Py thus has spectators holding their breaths between the accidental death of a friend and just before Romeo commits his tragic error of purposely killing the one who is now his cousin by marriage.

11 The black hole of tragedy or, as the Nurse puts it: «Why should you fall into so deep an O? » (III.3.90).

12 For Shakespeare’s resurrection of Hermione’s statue, see The Winter’s Tale (V.3).

13 My emphasis, first and foremost because the colour white pointedly indicates light (as opposed to the darkness of black). In this production however the set phrase «une nuit blanche», has a deeper meaning. It refers to a sleepless night in French, which is appropriate to the plot and its action filled night-time final scene, but it could also be seen as a commentary upon the theatrical eternity awaiting the lovers, as well as that of the text itself.