- Accueil

- > L’Oeil du Spectateur

- > N°9 — Saison 2016-2017

- > Adaptations scéniques de pièces de Shakespeare et ...

- > Doctor Faustus, directed by Maria Aberg, The Swan Theatre, Stratford, 28 July 2016, front ground.

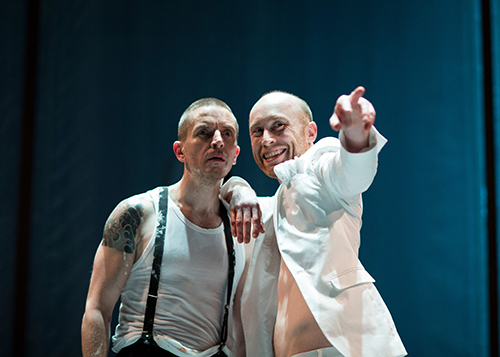

Doctor Faustus, directed by Maria Aberg, The Swan Theatre, Stratford, 28 July 2016, front ground.

Par Stéphanie Mercier

Publication en ligne le 05 septembre 2016

Texte intégral

1During the 2016 RSC Summer school there was an extremely enlightening lecture by Dr. Martin Wiggins, on, amongst other things, where Marlowe was creatively when he wrote Doctor Faustus. It appears it was an antithetical response to his previous works, in that two of the previous plays had dealt with the frailties of the body whereas, here, the motivations seemed to be the shortcomings of human consciousness. Indeed, just after the two-part Tamburlaine, where the main character goes out into the world to physically conquer all and yet dies with a sense of his life unfinished, Faustus has reached the ceiling of learning and attained the limits of logic. Refusing to explore the uncircumscribed boundaries of divinity, however, his own fantasy of power and universal fame involves him mentally summoning up evil spirits, with the help of forbidden learning, to go out into the world and resolve its secrets for him. Wiggins also pointed out how, by only choosing to reason that his sin would ineluctably result in an everlasting death, Faustus tragically ignores any possibility of everlasting forgiveness and cannot, therefore, I quote, “see the devils on stage waiting for their chance to catch his soul”. Aberg’s dark, fast production, that had purposely edited all comic moments from Marlowe’s script, precisely showed spectators the impact of this break-neck tragedy of a knowledgeable man sell his soul away and die, within the space of twenty-four years compacted, here, into one hour and forty-five minutes with no interval.

2The idea of exchange – and not only of scholarship for black magic – was present from the outset. The two actors playing the lead parts entered black-suited on either side of the stage to face each other. Both struck a match and he who had the one that first extinguished played the part of Faustus. Here it was the cerebral Scottish Sandy Grierson ; the more tensely physical Welsh Oliver Ryan played Mephistophilis. The random interchange device immediately raised levels of tension and electricity, provided an extra sense of danger and, as Ryan himself has pointed out, was an extremely efficient method of focussing, both for the actors and the audience. Indeed, the twenty-four years the main character has to live after summoning his (own) devils henceforth seemed no longer than the strike of a match. And, almost immediately, Faustus moved from looking into books stacked in the numerous cardboard boxes that littered the stage to undoing his braces, taking his shirt off and starting to rub paint on the floor in a form that closely resembled the cabbalistic circle on the frontispiece from the oldest extant edition of the play. The sustained tones of music (Orlando Gough’s musical accompaniment was all-through stupendous) under Faustus’s incantations – “yod-he-vau-he” – were soon joined by those of Mephistophilis. Yet, the self congratulation over becoming “conjuror laureate” was short-lived and signified, visually, as the production showed Faustus kneeling with this demon standing above him in a visual premise of the magician’s future hell on earth. Even the promised years of absolute power and infinite knowledge seemed immediately compromised in this instance as Mephistophilis swabbed spittle from Faustus’s mouth and left the stage, forefinger raised, in sign of the deal being definitively one-sided.

Photo by Helen Maybanks © RSC

From left to right Doctor Faustus (Oliver Ryan), Mephistophilis (Sandy Grierson)

3High sustained soul notes almost instantaneously joined Faustus filling a biro with his own blood, reaching a crescendo when Mephistophilis struck another match to liquefy the quickly clotted body substance to sign the contract. A back stage screen simultaneously showed indistinct devilish figures to a rising chorus of chanting. A shadow theatre of scholar-demons (Will Bliss, Ruth Everett, Gabriel Fleary, Natey Jones, Richard Leeming, Tom McCall, Joshua McCord, Bathsheba Piepe, Rosa Robson, Amy Rockson, Eleanor Wyld) was then projected and, as the voices faded to a whisper, the back suited, round rimmed spectacled characters came front stage to encircle the play’s main protagonist, naively delighted, even when his demand to know who had made the world remained stubbornly unanswered. An Evil Angel (John Cummins) and a Good Angel (Will Bliss) each stood in the balconies at either side of the stage, the latter in a last ditch attempt to save Faustus’s soul. The latter was now incapable of listening, however, to what seemed like a simple buzz in his ears and when Lucifer (Eleanor Wyld) appeared in a peroxide blond wig, red lipstick, black high heels, white trouser suit and white faced to show him some pastime, from hell, the talk was henceforth of the devil – nothing else.

4To sleazy cabaret style music, the Seven Deadly Sins sung the inventive “Seven Ways to Hell” while executing a modern danse macabre to create a terrifying pageant : this included lap dancing, whoops and cries, that was amplified in backstage projection. Then the troupe came front stage to present themselves to Faustus. Gluttony (Gabriel Fleary) wore a pig’s head mask and a pot-bellied skin suit, the high kicking Pride (Theo Fraser Steele) had a shiny lycra jumpsuit and flower ruff on, Covetousness (Rosa Robson) was spider-like, on stilt crutches, Wrath (Ruth Everett), in a lion-like half black, half white wig, pulled a knife whilst the black-masked illiterate Envy (Bathsheba Pieppe) called, as Fautus eventually would, that “all books were burnt”. Whilst Lucifer, wrapped around one of the pillars in the audience, looked on, Sloth (Richard Leeming), in Long Johns, braces and sleeveless vest, dragged himself, in front of Faustus, and then the transvestite Lechery (Natey Jones), in a white wig and tiara, licked the surprised scholars head. With just enough time for Mephistophilis to draw necromantic signs around the stage and cover Faustus’s feet with ashes, the pair then set off for Rome. Here, to a brass drum march, the unrepentant academic upturned the surprised golden coated Pope’s (Timothy Speyer) dishes and spilled his wine. These ultimately inconsequential events culminated here in the pontiff’s stabbing – infusing Faustus with a sense of power that was essentially down to the black devils that next invaded the stage – to encircle a group of white monks, who were chanting to an aggressive percussion rhythm, gradually encroach on their territory and, finally, chase them away from their holy ground.

5A sinister clicking sound announced the Emperor (Gabriel Fleary) immediately after. Requesting to see some proof of Faustus’s skill, Mephisotphilis played a practical joke on Benvolio (Tom McCall) by giving him horns, only to be called upon to transform the prank straight by the irate soldier – and ominously exit stage with a Stanley knife to do so. Because they had not realised that his twenty four years were not yet up, the furious ensigns then pulled Faustus about stage, kicked him in the groins, and, as the music swelled, wrapped a white plastic around his face, so that he could be suffocated and drawn, by both arms, and almost sodomised in the process. As Faustus came to life, demons entered to promise pricking thorns and broken bones to the miscreants. Benvolio was then possessed, and, as he screamed, the music swelled and died to evoke the grisly visual process. The visit of the obese skin-suited Duke (Theo Fraser Steele) and his equally as repulsive petticoat hooped Marie-Antoinette-wigged wife (Amy Rockson) then made way for a grotesque ball, where they exposed their huge bellies in a perverted Medieval morality that traded Adam for a nude (except for sixteenth-century shoes) Bacchus eating grapes, instead of apples : devils behind, noisily jittering all the while. The scholarly debate about fair ladies was just as distorted. As all drank, caroused and snarled, a female face and lips were shown back stage, a vision that seemed here to lead to Faustus’s astounded silence, and then to his request for Helen of Troy before his final departure for hell. To slow yearning chords, the scholar’s next lines were here spoken by Mephistophilis, a resourceful directive choice that left the scenic space open for a choreographed mime, the dramatic irony and power of which was devastatingly moving. Helen (Jade Croot) appeared on stage to advance towards the academic, jump into his arms, take his head into her hands and then, rag-doll-like, be tussled with, to no response. And then, as if being raped by him, she struggled free and ran in circles around the stage. He spat into his hands and spread the spittle over his head in a desperate attempt to experience her embrace, ran around the stage himself in an evident last ditch attempt to feel her life-force – to no avail because she was ultimately only a devilish dream of his own making.

6The other devils next entered as the clock struck twelve and, in his last moments, too late, Faustus looked up to heaven. When he had finally resigned himself to his ultimate fate, still holding a book, he thrust the Stanley knife into his chest and the cinder-footed Mephistophilis came on stage to claim the scholar’s soul. In the lecture, I also learnt that “Faustus” should most probably be pronounced with the Latinate “Forstus” to make the most of the assonance on “forstus-fortune (as in “Dr. Lucky”)-fortitude”. This production certainly, and wonderfully, expressed to the full what Wiggins calls a terrible misnomer for someone who would endure the eternal torment of hell, an anguish that, (un)fortunately because the production so perfectly captured what Marlowe was most probably trying to convey, we could share only a too short time with him.