- Accueil

- > Shakespeare en devenir

- > N°15 — 2020

- > Varia

- > “There’s a [space] for us”: Place and Space in Screen Versions of Romeo and Juliet in the Spanish 1960s: West Side Story (R. Wise and J. Robbins, 1961), Los Tarantos (F. Rovira-Beleta, 1963) and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta (A. Paso, 1969)1

“There’s a [space] for us”: Place and Space in Screen Versions of Romeo and Juliet in the Spanish 1960s: West Side Story (R. Wise and J. Robbins, 1961), Los Tarantos (F. Rovira-Beleta, 1963) and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta (A. Paso, 1969)1

Par Víctor Huertas-Martín

Publication en ligne le 18 février 2022

Résumé

This article examines the critical reception of the film adaptation of West Side Story (Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise, 1961) in Spanish culture and cinematography. It looks into two other screen versions of Romeo and Juliet: Los Tarantos (Francesc Rovira-Beleta, 1963) and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta (Alfonso Paso, 1969). West Side Story remains in the Spanish cultural memory as a filmic event associated with the arrival of foreign influence amidst national-catholic dictatorship. I will use the variables “place” and “space,” which distinguish, on one hand, proper orders established by authority and, on the other hand, areas transformable by interactions and changes, and will refer to Shakespeare’s presentist criticism, French cultural theory and French Film Theory as lenses. I will examine West Side Story’s 1963 Spanish reception material as well as its possible interactions with the webwork of cultural forces in operation amidst the 1960s Spanish culture. Then, I will examine the mise en scenes of Los Tarantos and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta focusing on the forms in which characters, places and camerawork contribute to create spaces, i.e. places permeable to change and transformation through human interaction.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Texte intégral

1Steven Spielberg’s upcoming remake of West Side Story bears witness to the impact of a story which is, as both play and film, “into our collective cultural consciousness.”2 This article inter-connects the impact of West Side Story in Spanish culture and in the cinematography of two Spanish screen adaptations of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: Los Tarantos (dir. Francesc Rovira-Beleta, 1963) and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta (dir. Alfonso Paso, 1969). Inter-connected thematically, temporally, and stylistically,3 these three films are representative of a shift in screenings of the play. Franco Zeffirelli’s interest in Jerome Robbins’ musical while adapting Romeo and Juliet for the screen has been pointed out to suggest that West Side Story influenced other European screen adaptations of Shakespeare’s play.4 Renato Castellani’s film’s nineteenth-century backdrop has been contrasted with Zeffirelli’s creation of a space which turned Verona streets into an “additional character” in his 1968 film version.5 Arguably, this rethinking of space as more dynamic and less stagy than the one in classical versions was due to stylistic shifts towards emphasizing the kinetic and expressive potentialities of space and reality which 1960s films inherited from Nouvelle Vague and documentary-based approaches to filming.

2Our three films are, likewise, distinguished by their dynamic articulations of spaces. West Side Story’s song “Somewhere” meant in the 1960s “longing and aspiration while steering clear of false hope or platitudes.”6 I argue that such a spirit transfers to other Romeo and Juliet films but, rather than looking for freedom “somewhere,” as this essay shows, the films examined delve on life-affirming transformations of places–areas subject to proper order–, which become spaces–areas which accept transformation. Drawing from cultural theory–Michel de Certeau–and film theory–Gilles Deleuze–and Shakespeare Studies, I will explore place and space regarding the Spanish critical reception of West Side Story and in the mise en scenes of Los Tarantos and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta.

I. Context

3The only two Spanish stage productions of West Side Story are marked by the film’s impact in the Spanish cultural memory. Ricard Reguant’s staging of the play (1996-1997) followed the screenplay–not the stage play–to avoid shocking audiences familiar with the film.7 As I argue in a forthcoming review of Som Produce’s recent production of West Side Story (2018-2020), directed and choreographed by Federico Barrios, the production company capitalized on the novelty of presenting a production faithful to the original Broadway stage play (26 September 1957, Winter Garden Theatre) and on its affiliation to the 1963 Spanish première of the film.8 For instance, Som Produce’s production Making Of mimicked the film’s aerial shots to present Gran Vía–Madrid’s theatreland–. Designer Antonio Belart’s costumes mimicked those worn in the film since he considered that these patterns were “in the spectator’s retina.”9 Copies of the film soundtrack were sold in the theatre too. Reguant’s production used the film poster as blueprint and, though Som rethought it playfully by making the originally abstract fire escapes become sections of Upper West Side buildings, it used the emblematic three silhouettes of Bernardo and two Sharks dancing while taking over Jet territory in the film’s “Prologue.” As I argue in the above-mentioned review, “Som’s publicity strategies strove to bring together audiences nostalgic for the film and audiences hungry for the original Broadway piece”.10

1

Crédits : Focus

2

Crédits : Som Produce, West Side Story

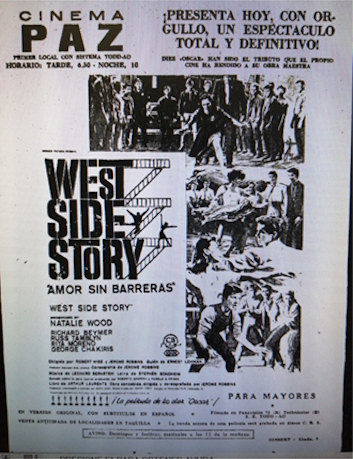

4West Side Story’s première at Cine Paz (Madrid) on 1 March 1963 was marked as historic in Som Produce’s paratexts. According to Som Produce’s blog entry “Aniversario del estreno,” the film arrived when Spanish freedoms were curtailed by the dictatorship which followed the military coup d’état of 1936. Despite the political backwardness resulting from such turn of events, the nation seemed, as the blog affirms, to be starting in the early 1960s to see lights at the end of the tunnel.11 The regime’s propaganda expectedly smiled with optimism in the 1963 press. But it is contended that that twentieth-century Spain’s progress toward European democracy became possible, in part, thanks to its contact with the international sphere and to commerce, both of which were boosted in the 1960s.12

5New possibilities were then envisaged in the arts. As it is argued, in 1960s Spain literature and cinema started to tread freedom paths.13 Regarding cinema, it is admitted that in the early sixties the regime relaxed censorship following suit with European neighbors.14 This didn’t mean an end to censorship. In fact, as an anonymous’ editor’s letter in a 1963 issue of the journal Otro Cine remarks, it was feared that freedom could camouflage what were regarded as undesirable contents deserving suppression.15 Refusals to romanticize the decade’s apertura do not disqualify the scholarly agreement that under the aegis of Minister of Culture and Industry Manuel Fraga-Iribarne and Head of Cinema and Theatre José María García Escudero, subsidizes, distribution, exhibition and censorship mechanisms increased and were concretized and refined.

6Ideas of hope are collected in the blog post which continues saying that, amidst repression, Spanish audiences must have found in West Side Story a window to a different world where others suffered the intolerance which they themselves were suffering. In fact, the film’s Spanish title–Amor sin barreras–, highly disregarded by Spanish reviewers, explicitly foregrounds the play’s recurrent motif of barriers of all sorts–dividing lines, warning signs, walls, fences, etc.–with the added value that the semiotic richness of barriers could agglutinate multifarious feelings of division and separation in the local postwar culture.

7The post’s picture showing the Cine Paz at Calle Fuencarral, at the heart of Madrid, suggests the space where hopes, pleasures and dreams of cinemagoers amalgamate and give way to a forward-gazing local mythology. Though Som Produce’s use of this material was driven by market interests, it is significant that the company endorsed a sentiment associating the film with upcoming freedom precisely at a time, near the end of 2018, in which Spain’s social-democracy was threatened by a wave of populist national-catholicism blended with neoliberalism. Social alarm at a possible return to pre-democratic Spain became topical.

3

Crédits : Som Produce, “Aniversario del estreno”. Cine Paz exhibiting West Side Story in 1963

II. Freedom, Spaces and Film

8Research carried out on appropriations of Romeo and Juliet in Spanish adaptations largely focuses on establishing distinctions of highbrow and lowbrow stagings of the play. These perspectives lead to conclusions which, unsurprisingly from a progressive political vantage point, do not encourage optimistic readings.16 My approach, nonetheless, proposes to rethink Shakespeare’s appropriations from a progressive perspective by resorting to the concept of freedom in both the real and the cinematic spaces rather than on high-low cultural binaries.

9Ewan Fernie regards Shakespearean freedom as a life-affirming individual and community-led struggle whose interpretation requires creativity and acknowledgement of its risks.17 But the type of Shakespearean freedom advocated by Fernie demands social responsibility and acknowledgement of what Hegel terms sittlichkeit, aka conventional culture.18 Sittlichkeit imposes limits to freedom but opens up to ideal conditions facilitating compatibility of subjectivities and social programmes. To analyze conditions for freedom in geographic contexts, Michel de Certeau’s thoughts on social relations and tactics in space, collected in The Practices of Everyday Life (1980), lend a second theoretical strand. For De Certeau, “place” is the order “in accord with which elements are distributed in relationships of coexistence.” As he continues, “The law of the ‘proper’ rules in the place” are articulated by “elements taken into consideration [which] are […] each situated in its own ‘proper’ and distinct location.”19 Contrariwise, “space” involves “vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables... [it] is composed of intersections of mobile elements.” Spaces are actuated by movements of these elements “in a polyvalent unity of conflictual programs or contractual proximities modified by the transformation accused by successive contexts.”20

10To specifically think the cinematic space in the terms suggested with the study of space, Gilles Deleuze’s film theory affords a third strand. In his two theoretical works, Cinema I: Movement-Image (1983) and Cinema II: Time-Image (1985), he defines cinema as a series of successions of “any-instant-whatevers” as opposed to privileged instants from ancient paradigms. In the essence of any-instant-whatevers lies the transformative quality of movement on screen. Drawing from Henri Bergson’s theses on movement, Deleuze refers to the “any-instant-whatever” as something which does not constitute a synthesis–as the privileged instant does–,21 which do not form poses but sections,22 which conform “the description of a figure which is always in the process of being formed or dissolving through the movement of lines and points at any-instant-whatevers of their course.”23 This is not to say that privileged instants do not thrive in cinema, as they indeed do, but that they do not function as poses. Prominent instances which cumulatively construct space-time,24 free from the fixities of poses, any-instant-whatevers organize and redistribute bodies and systems at large. And, following this logic, the more expressive possibilities of depth, dynamicity, saturation, and rarefaction the camera develops, the greater is cinema’s potential to multiply the possibilities of any-instant-whatevers.

11We will utilize Deleuze’s metaphysical “time-image.” Overall, it contributes to constructing new realities via implicating objectivity with the imaginary and the subjective.25 The time-image potentially fulfills cinema’s aim to restore human belief in the world and in the power of body and intellect to transform it.26 Looking into its potentialities will support the ideological basis of our analysis.

III. West Side Story

12This section explores the impact of West Side Story in Spain–premièred on 1 March 1963–through some of its para-texts as well as stories interrelated with the film’s reception. In the advertisement for Paz’s première–appearing in newspapers like ABC, the production was announced as a ten-Oscar success with songs in English unprecedentedly surtitled in Spanish. That West Side Story was not, according to testimonies, read politically but as a spectacle and a moving love story27 is a view confirmed by reviews and commentaries in the 1960s press and in later Spanish reevaluations of the film. These almost invariably rather center on the film’s aesthetics.

13Nonetheless, the censors noticed moral risks in this film. The 1963 report issued by the Secretariado Internacional de Publicaciones y Espectáculos noted “objections regarding content and form” on some sequences.28 Praising the film’s artistry, the report pointed at violent content, which gained the production a score of 3R – i.e. “recommended, with reservations”. The Secretariado’s catholic sensitivities were appeased by the idealized love embodied in the character of Maria, who was presented in family-friendly scenes like the Bridal Shop’s pantomime. Maria’s symbolic power as forgiving figure was noted by the censors who saw her redemptive influence on the kneeling Tony after the rumble.29

14Despite this controversial reading which reduces Maria to be Tony’s redeemer, for many other reasons, as actress Talía del Val says, women who wrote fan mail to her after seeing Som Produce’s show said to her that the film had value in their lives. They interconnected their enjoyment of the play with their experience of the film by conjuring up memories of their own or their mothers and grandmothers’ stories of resistance and self-reliance during the Spanish postwar.30 And, looking into Paz’s advertisement, printed in the ABC newspaper on 1 March 1963, it seems likely that the publicity meant to capitalize on the film’s appeal to women. The picture above captures Maria’s body’s motion towards Tony. Exposing the gangs’ and the cops’ impotence, Maria’s body brings warfare to a halt and opens up the space’s possibilities to reconciliation. For De Certeau, gestures transform entire scenes.31 And women in West Side Story, as Barrios suggests, effect such transformations.32 As opposed to male characters–shown performing violent acts or as incapacitated (as Bernardo and Tony, below)–, women’s gestures concretize life-affirmative values. In the second picture, Anita (Rita Moreno) dances “America” taking stage center in celebration of what the future in New York has in store for Puerto Rican women ready to embrace freedom and work ethics. In picture three Tony and Maria dance a “Chacha” at the gym in a scene in which Wood’s open plexus and luminous expression render her presence more proactive and vital than Beymer’s.

15Spatial features of the poster might have resonated with the aspirations of cinemagoers. The dancing couple soaring over a staircase in the film’s logo invite thinking of rising up far from the oppressive atmosphere of the place. This idea, which had been developed in Oliver Smith’s stage design,33 might have resonated with the Spanish middle classes’ aspirations to afford flats at unprecedented prices in an increasingly affluent economy.

4

Crédits : ABC, West Side Story Advertisement for Cine Paz. ABC, 1 March 1963, p. 28

16The film’s recurrent revivals brought to table divided views on its relevance. But critics and reviewers reckon its “peculiar mythology”34 and undoubtable popularity. And it has been in the years preceding Som Produce’s première that such mythology has been variously invoked. During its 75th Anniversary (9-15 November 2018), Cine Paz invoked West Side Story’s status as a major landmark in their history. The cinema displayed the picture of Chakiris’ visit for the 1964 commemoration of the film after its 365-day run at the venue as well as Guestbook’s testimonies which, to some extent, prove Som Produce’s hypothesis on the enthusiasm that West Side Story produced in 1960s young couples. These couples, as some testimonies suggest, found in the film the excuse to fall in love with each other and remain together for life. Though anecdotal and scarce, these stories contribute to justify the film’s optimistic associations in the Spanish cultural memory and, indirectly, establish parallels with the story if we consider the intolerance pervading Spain’s national-catholic regime. Catalan writer Marcos Ordoñez compiles various stories related to the film’s arrival to the Barcelonese Cine Aribau in 1963. He cites Joan Ollé’s description of his aural experience of West Side Story near the Aribau’s patio, where Ollé could hear “the film songs… through the open windows in summer…”. As Ordoñez continues, “The women were humming Bernstein’s tunes as if they were cuplés, and [Ollé] was convinced that Tonight would forever be the tune of the family dinner.”35 But if the songs of West Side Story contributed to constitute dream-like spaces for the aspiring Barcelonese middle classes, Ordoñez offers a West Side Story anecdote speaking for the experience of the marginal: the story of la novia de Bernardo, which became popular in the local news. Regarded as an unbalanced character, Florentina–aka “Bernardo’s girl”–visited the Aribau for six months to see George Chakiris on screen. When Chakiris travelled to Barcelona for the 1964 film’s commemoration at the venue, the executives asked Florentina to hand a bunch of flowers to Chakiris, who kissed her on the cheek. But to this success West Side Story tale, Ordoñez adds ambivalent references to Barcelonese migration to and from America during pre-war and post-war agglutinating them all under the folk song “Yo tengo un tío en América.” This version of Sondheim and Bernstein’s song indeed alluded to the many “uncles”–in Spanish, tíos–absent from their families trying their fortunes abroad or seeking refuge from political repression or poverty.

IV. Los Tarantos

17Basing his script on Alfredo Mañas-Navascues’s play Historia de Los Tarantos–premièred in Teatro Torres, Madrid in 1962–, Francesc Rovira-Beleta, as Deborah Madrid-Brito says, blended elements from this play’s and Shakespeare’s text. Mañas-Navascues’s relationship to Shakespeare’s tragedy is difficult to sustain, but Rovira-Beleta extracted elements from the Aragonese playwright’s work relatable to Romeo and Juliet and expanded them in his own film.36 Instead of setting the film in an unknown Spanish sea village–as in the play–, Rovira-Beleta set the story in Barcelonese marginal areas–Somorrostro and Motjuic–and central areas–Sants and Plaça de Espanya–, the purpose being to resituate Romeo and Juliet in the city’s Romani culture. The Tarantos (Montagues) and the Zorongos (Capulets)–the latter supported by the Picaos, headed by Curro (Paris’s equivalent)–were the two Romani families. Romeo and Juliet became Rafael (Daniel Martín) and Juana (Sara Lezana). Their fate was to die together under Curro’s blade as they tried to hide together in Rafael’s dovecoat. Often taken as a “West Side Story gitano,”37 the commercial context of distribution of Los Tarantos facilitated comparison between the films. The Secretariado Internacional de Publicaciones y Espectáculos (SIPE), condemned the film’s loss of Shakespearean quality, its crudity and the market-motivated attempts to equate it with Robbins and Wise’s achievement.38 And, as said, this coincidence, as well as the film’s unsuitability to fit pre-established genres, led to its critical disregard.39

18Highlighted as a film which doesn’t merely reinforce the stereotypes on the Romani culture, Los Tarantos features its transformative potential established in the film’s first shot. This exemplifies an any-instant-whatsoever, following Deleuze’s terminology. Though frozen for several minutes, rather than presenting a static synthesis of privileged poses, the frame depicts a changing world: a luxurious and light city where commerce, business and human interaction take place as Romani folks take stage center. Against the city’s technocratic ethos, gypsies are merry upholders of traditional forms of subsistence, such as flower selling amidst an industrial city. Rovira-Beleta links gypsy culture and prestige cinema via title credits describing the Oscar-nominated film while exhibiting the best of cante jondo, flamenco and bulerías, the name of the flamenco star Carmen Amaya, her cuadro flamenco together with names like Peret’s and Antonio Gades’s.

5

Crédits : Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos. Opening shot with Rafael (Roberto Martín) and his family (center) walking to the marketplace

19Though critics have praised Rovira-Beleta’s attempt to represent Romani culture beyond stereotypes,40 he took commercial advantage of the popularity of gypsy culture and of Somorrostro, both of which gained fame thanks to Amaya’s worldwide star status. Somorrostro included areas of Barcelona known today as Hospitalet, Poblenou and Port Olimpic. This originally marginal area increased its population in the early twentieth-century becoming a popular and visitor-attracting gypsy neighborhood until it was demolished in 1966. As a suggestion of this, on screen, Montjuic–another popular gypsy area–, holds Coca-cola and Mahou logos anticipating future assimilation by dominant culture.

20Yet, following De Certeau, subjects also outwit technocratic systems momentarily without eventually escaping it.41 The Tarantos stand their ground in the city, which they also occupy – e.g. in areas such as the Café–, much to the Zorongo’s nuisance. Actually, it is Rafael who–in the film–first uses a blade against Sancho–Tybalt’s equivalent–during a broil near the market as the Picaos attack the Taranto women for trying to occupy a space in it. Repeatedly, the Tarantos fight back and resist the Zorongos and the Picaos’ aggressions, often prevailing against them, seeking to establish themselves at the city center. But areas of confluence give way to interactions as well as to interdictions. Members of both families, such as the children Jero (Aurelio Galán) and Sole (Antonia Singla) team up while dancing, running through the streets, sharing and helping Juana and Rafael meet in secret. For De Certeau, frontiers harbor spaces for conjunctions giving way to new communication forms.42 In Jero and Sole’s case, though not the only means of interaction at all, their shared culture of dancing plays a crucial part in mutual bonding.

21And such is the way in which Rafael and Juana’s relationship is established. Presenting Juana and Rafael’s first encounter via body language, Rovira-Beleta takes a road different from Wise and Robbins’ straightforward presentation of Maria and Tony’s meeting. West Side Story’s lovers, unable to find a place for themselves, need to find it elsewhere, yet Juana and Rafael’s bodies produce their own space in Somorrostro. To appreciate the way in which this takes place, Rovira-Beleta’s camerawork’s cumulative effect may be studied through Deleuze’s categorization of images. “Affection images” arrange elements to constitute a power which is never actualized but which fosters new qualities.43 Such process is seen through a succession of close-ups exchanged between Juana and Rafael: To Juana’s initially reluctant gaze, Rafael opposes tentative gestures and small approaches leading to their clapping together. “Reflection-images” implicate interims between actions and relations in which signs are forces of attraction and inversion giving way to new situations.44 A multiplicity of such signs of attraction ensue Rafael and Juana’s proximity. They don’t dance together but she ties her shirt, offers her dancing solo to him, and presents gestures to him. For Deleuze, the screen produces belief in the power of the body’s discourse.45 Juana and Rafael’s bodies have been able to transform their space, the camera articulating their interactions. But this doesn’t stop here. When the wedding guests interrupt the lovers, Rafael tries to kiss Juana, a gesture whose obviousness clashes with the suggestive subtlety of the previous interactions. Rovira-Beleta alters this with a bold spatial displacement. Rafael and Juana escape to the beach. “Movement-images” constitute autonomous worlds with centers and openings.46 In a radical departure from the space they have created, traversing physical and emotional barriers, Rafael and Juana reach the water and submerge their bodies into it. The next sequences show Rafael and Juana’s bodies as creators of space. Their tranquility near the beach and their tears of reaction to the knowledge that they belong to rival families affect the atmosphere, which, whether in merry or tragic mood, seems to emanate from their emotions.

6

Crédits : Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos. Rafael (Roberto Martín) and Juana (Sara Lezana) clapping

7

Crédits : Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos. Juana dancing for Rafael

8

Crédits : Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos. Juana dancing for Rafael

9

Crédits : Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos. Rafael and Juana under the water

22As in Rafael and Juana’s meeting scene, water signals areas of encounter in later sequences. It mutates as snow covering Parc de la Ciudatella where they meet to discuss Juana’s future marriage with Curro arranged by Zorongo. Strategically situated in Los Tarantos’s geography as intermediate point between Somorrostro and the city center, Ciudatella is not just any park. It symbolizes the civic aspirations of Juana and Rafael’s love. For De Certeau, spaces like Plaçe de la Concorde evoke civic qualities.47 A site for the Catalan Parliament and numerous scientific, educational and institutional spaces, Ciudatella has been, since its nineteenth-century transformation, held in regard as public space per excellence. In the nineteenth-century its military facilities were replaced by gardens inspired by European models and Roman and Florentine villas and the parc was site for the 1888 Universal Exhibition. Nearer the time of the film, Franco’s government had for long neglected the parc’s maintenance. And, to the neighbors’ indignation, it tried to eliminate lines of trees in it and it was thanks to the citizens’ joined efforts that on 21 December 1951 the park was declared of public artistic and historic interest. This civic victory guaranteed the park’s protection and survival. This historical background turns this park into a semiotically rich cultural space evoking the city’s civic history. In Fernie’s reading of Romeo and Juliet, freedom remains in Villafranca–aka Freetown, in Fernie’s work–, the Prince’s residence, but potentially also momentarily in Verona’s spaces, for instance, during Capulet’s celebration.48

23One challenge for a reader of the adaptations is to find whether civic opportunities such as this one are to be found in Verona or, as is the case, in Barcelona. It is not insignificant that Rafael and Juana’s meeting takes place in Ciudatella–whose cultural history adds significance to this encounter–and that, immediately after this, they intend to request Padre Lorenzo’s support at the cathedral. The priest’s harsh dismissal implicitly suggests that the Church’s refusal to support this couple transforms the cathedral space into a cold, unwelcoming site to contrast with the open, civic and free space of Ciudatella. Opposed to the Ciudatella’s civic spirit, the luxurious lights of the city often contrast with such it and with the folk culture and simplicity of Somorrostro and Montjuic. Deleuze remarks as a feature of postwar cinema that irrational cutting produces distorting effects.49 Thus, he opposes the notion of organic montage defined by David W. Griffith to the post-war model, based on fast-cutting and arrangement of disconnected pieces. This ideological view of postwar cinema seems useful to define the dialectics between city–whose frantic advance and progress parallels the ruthlessness with which the Picaos and the Zorongos associate progress to an ethos of competition and elimination of the Tarantos’ way of life–and gypsy neighborhood as irreconcilable spaces. Spaces, as dreamt and created by Rafael and Juana, become memories evoked through words and, less and less intensely, through guitar sounds and views of the sea in the final shot after they are killed in Rafael’s dovecoat, the lover’s last refuge from the city’s intolerance.

24Rovira-Beleta refuses to acknowledge an influence from West Side Story.50 But he takes his vantage point from Ernest Lehman’s script in Los Tarantos’s final scenes. Before Tony dies in the former production, he and Maria cherish the place they need to find elsewhere:

Tony (weakly):

I didn’t believe hard enough.

Maria:

Loving is enough.

Tony:

Not here. They won’t let us be.

Maria:

Then we’ll get away.

Tony:

Yes, we can. We will.51

25Lehman accentuates an already developed idea across the film: the need to find “somewhere a place for us”. Rovira-Beleta’s dialogue–collected in the film’s dialogue transcription52 develops this idea too:

Rafael:

Cuando amanezca (sic) iremos de aquí. Lejos de nuestras familias.

Juana:

Yo no tengo familia. No quiero su nombre. Ya solo eres tú, para siempre, mi familia y mi nombre.

Rafael:

Debe haber un lugar en el mundo “pa” nosotros, donde se pueda vivir sin odios.

Juana:

Juntos lo encontraremos.

26Rovira-Beleta recasts paraphrases of Lehman’s script with Shakespeare’s wordplay on family. But while this final scene endorses WSS’s ultimate statement that “there’s a place for us… somewhere,” Rovira-Beleta adds as coda the characters re-enacting of the actual changes they brought to the world there by referring to material elements of space such as the water, the snow in the park or larger materialities–such as the beach and the park–which become, in the character’s minds, ingrained with their own dreamlike view of their brief love story. This involves a radical departure from the basis established by Lehman’s–based on Arthur Laurent’s–script, which, as said, emphatically reaffirms the need to find another place somewhere else.

Rafael:

¿Recuerdas el beso bajo el agua?

Juana :

Y la cita en la playa… Y la nieve en el parque…

Juana (off):

Ha sido todo como un sueño. (31)

27Thus, the film’s tragic end is not so much, in this sense, connected with their deaths. In fact, Curro hasn’t still arrived at this point–but with the unbearable fact that a deeper and more a sustained and collective transformation of place into space has failed. And yet, despite the film’s tragic ending, Rovira-Beleta implicitly proposes, as shown, a civic alternative, at least once.

V. No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta

28Alfonso Paso’s film’s first sequence contrasts nature’s abundance–through a series of documentary nature images–and poor life conditions in the Madrid outskirts resulting from the implementation of the government’s 1960s poorly developed housing. In this decade, Madrid received migrants from the whole national territory and barracks were built around the capital. As Pedro Montoliú’s study proves, this made the city’s urban development difficult, as successive plans failed due to government’s incompetence, their neglect and their allegiance to private developers. While the government publicly proclaimed the satisfactory results of the developments, the ‘picaresque’ spirit of developers did its worst and installations in barracks were often neglected so that neighbors could be expelled, the lands sold and other homes built.53 Amidst this bleak backdrop, the humorous key with which the film develops presents an opportunity to read this production as a politically transgressive Shakespearean appropriation. The film’s beginning presents life on the streets as a series of quarrels between resentful neighbors belonging to a disappointed middle-class, whose members dreamt of belonging and make a space of their own in the capital.

29According to Deleuze, it is “necessary to go beyond the visual layers; to set up a pure informed person capable of emerging from the debris, of surviving the end of the world”.54 Paso’s Romeo and Juliet seem fit to the task in this sordid environment. Roberto Negresco (Emilio Gutiérrez-Caba) and Julia Caporeto (Enriqueta Carballeira) are described as relatively inefficient to communicate and as rather slow. For comic effect, Roberto is affected by dyslalia so he cannot pronounce /p/ sounds, a fact that thematizes his inability to dialogue with his father. The quarrel between Caporetos and Negrescos seems explained by a webwork of ideological, taste-based and ideological differences. Living opposite each other, Rosario (Florinda Chico) and Trinidad (Laly Soldevilla)–Caporeto’s and Negresco’s wives respectively–compete on the legitimacy of their musical tastes. Rosario sings coplas, such as Estrellita Castro’s “Mi jaca,” whereas Trinidad prefers Massiel’s “Lalala,” Eurovision’s Spanish hit in 1969. These and other differences activate mutual class-based disregard. Profession and regionality appear as factors of division too. Antonio Negresco (Antonio Almorós), a waiter, dismisses Nemesio Caporeto (José Luis López Vázquez) as “the bus driver.” Nemesio dismisses Caporeto–and almost everyone–for lacking structure, logic, or reasoning–terms he takes from a book he reads at work and at night–and conforms to the type of irate individual who preaches balance and reason. Trinidad shows pride at her husband’s Catalan pedigree associating her “household” to a history of dignified socio-political resistance.

30But such concerns escape Julia and Roberto’s understanding, their alleged lack of brightness being rather their families’ inability for collective problem-solving. Such obtuseness extends to younger individuals such as Julia’s boyfriend, Cayetano (Manuel Tejada), a flick-knife-carrying chulo with a certain status but ready to be as violent as his elders. These adults embody what some intellectuals regarded as a national mediocrity, which disregarded other nations governed as popular democracies where cars weren’t affordable.55 Per contra, it is pertinent to consider the film’s use of anglophone pop culture and US filmic reference. It associated this film with other Spanish films of the period, also influenced by anglophone counterculture, which, as Vicente J. Benet says, encouraged a rebel spirit and rupture with adult conventionality by tackling difficulties of the youth in the domestic sphere.56 This transformative zeitgeist defines Paso’s characterization of Roberto and Julia, whose conversations reveal a desire to transcend hatred. Their first encounter on screen invites study through “affection-image.” When close-ups reveal Roberto and Julia’s affection behind their rooms’ bars, their sympathetic glances transform the atmosphere’s quality. Combining dialogue, a long shot of the road and a soft-paced instrumental version of the film’s theme, a space emerges during Roberto and Julia’s first affectionate exchange in voice over. It is, perhaps, not accidental that Paso frames this dialogue by just focusing on the street, rather than on the speakers. For the shot agglutinates the voices in tune with one another producing union between opposing sides sensorially and suggestively redefining what was a space of conflict.

10

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta. Julia (Enriqueta Carballeira) looks through her window bars to Roberto’s room on the other side of the street

11

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Juliet. Roberto (Emilio Gutiérrez Caba) looking to Julia’s bedroom from his own window

12

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Juliet. The street while Roberto and Julia exchange confidences voice over on their feelings about their families’ hatred

31Paso’s film acknowledges West Side Story’s precedence in parodic terms.57 Cayetano’s knife-fight–a silly imitation of odd movements of WSS’s “Rumble”–takes place with a gang leader whose hairstyle resembles Chakiris’. The garage turned into dancing space resembles the one where the Jets play “Cool.” To film Roberto and Julia’s first encounter, Paso initially mimics Wise and Robbins’ lighting for Tony and Maria’s meeting, then establishes caesura between world of dancers and world of lovers in which the others freeze and disappear when Roberto and Julia leave the garage, their bodies stuck against a wall, exchanging love promises in an old-fashioned language estranging them both from the ordinary language of others. Rather than blending the real and the imagined, Paso has the characters reaffirm their love by imagining a space in the place they inhabit. Additionally, Julia’s attempts to tell her father about Roberto, brings allusions to West Side Story. She wears a red scarf like the one Wood takes in the final scene. Caporeto, trying to awkwardly teach Julia where children come from, conjures up principles of modernity: “Estamos en la era del átomo, de los cohetes espaciales y del ‘Best Sid Estori’”. Nemesio’s ‘macaronic’ reference to West Side Story might be used to endorse Som Produce’s hypothesis on the association between West Side Story and Spanish apertura.

13

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Juliet

14

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Juliet

15

Crédits : Paso, No somos ni Romeo ni Juliet

32But, since Caporeto’s obtuseness impedes him to live up to his principles, Paso alters the story’s course and has Roberto and Julia try to actually find “somewhere.” Taking into account De Certeau’s premise that possibilities of transformation appear in movement whenever movement interweaves elements in places,58 we observe that, walking through the outskirts, Roberto and Julia benefit from the goodness of vagrants and outcasts such as Boquerón, the daughter of a prostitute, who gives them shelter at night. The prostitute, sociologically circumscribed to a different place, offers the couple her room, a space whose sky-blue light wall-painting and golden bread footboard top rails suggest the saintly ambience of a chapel more welcoming than the parish where Roberto and Julia find the priest’s harshness. And this is just one of the instances in which marginal characters lend help to Julia and Roberto or to the family’s endeavor to find them.

33If these instances of the transformative potential of peripeteia do not suffice, the final scenes confirm that confluences of space contribute to consistently modify the general neighbourhood’s atmosphere and rearticulate Caporeto and Negresco’s leaderships in the place. The final scene’s voice-over posits the truthfulness of the story and invokes the hope that love’s power will bring happiness to all. The film brings about change in the characters’ collective universe. Regarding this, Deleuze affirms that time is metaphysical–not empirical–and capitalizes on the indiscernibility of the real and the imaginary.59 Moves and interactions have built bridges across the neighborhood which result from Roberto and Julia’s desires for reconciliation and the neighbors’ eventual contagion of those desires. One way of reading the conclusion is that the lovers, returning like ghosts from the garage where they had intended to take refuge, are saved by the same patriarchal order which started the conflict in the first place. Even in the Spanish filmic context of the 1960s, in which there are instances of feminist rebel attitudes against patriarchy, such a reading certainly compromises an optimistic interpretation. For the mysoginy with which Negresco and Caporeto lead their households is not subverted. Notwithstanding this dimension, Roberto and Julia aren’t powerless. Julia takes the initiative for the most part of the film. Contrarily to the general view, she thinks that this world needs Romeos and Juliets so love replaces hatred. In other words, she recognizes the need to revive Shakespeare’s love story in this world, not another. Likewise, though clumsily, Roberto stands up against Cayetano even admitting his fear. As he says, people need to stand up against those who carry switchblades. The political importance of such statement could not be underrated at a time in which the worst part of Francoist repression was just beginning. As Casimiro Torreiro explains, strikes and the advances of the Communist Party increased political agitation. Towards the end of the 1960s, the government reacted by suspending constitutional guarantees.60 It was high time to face up a violent regime if people wanted democracy. And the regime was prepared to respond.

34Also, though the film does not fundamentally transform filial-parental relations, Caporetos and Negrescos eventually successfully achieve authority. But such authority is community-based. A community, gathered to see the families emerging from the garage, emerges where discord used to be the norm. Paul Kottman presents the tragic destinies of Shakespeare’s lovers as “the story of two individuals who actively claim their separate individuality […] through one another” and whose “love affair demonstrates that their separateness is […] the operation of their freedom and self-realization.”61 Per contra, Paso’s film is interpretable through Fernie’s conception of Shakespearean freedom as both individual and collective. The neighborhood remains what it is, its conditions nevertheless are nearer a space: one in which the rules of order are transformed by positive forces of interaction.

Concluding remarks

35Close-reading Shakespearean screen appropriations taking into account the features of space does not only allow us the chance to reclaim the interest of appropriations neglected due to their lack of seriousness. It also permits us to strengthen a critical history of Shakespearean interpretation which, in the last decades, cultural materialism and presentism have been elaborating. We are indebted to Fernie’s work for the reminder that Shakespearean plays are not popular because they adhere either to elite or to mass culture, but because they consistently negotiate the rights of the individual to be what he/she is–to the point of excess–and society’s rights to collectively define its cultural norms, not to conform rigid structures, but to build civic spaces where conditions to the ideal make it achievable. Taking popular beliefs on one specific adaptation seriously, this essay has explored the transformative potential of these appropriations in mise en scene and critical reception. Following suggestions to explore space in Romeo and Juliet by critics who point at the importance of the city as a utopian, inescapable space where individuality needs to negotiate with the collectivity,62 Looking into spaces in Shakespearian appropriations helps us identifying instances of mutual engagements and negotiations. These are presented via interconnections of bodies, via interactions in intermediate spaces, via insertions of dream-like episodes in people’s encounters and by ingraining the imagined, the ideal space, a socially and affectively constructed setting, into the reality of the place.

Bibliographie

ANONYMOUS, “Aires Nuevos,” Otro Cine, Año XII (59), 1963, p. 243.

ARANZUBIA-COB, Asier, “Los Tarantos de Francisco Rovira-Beleta (1963) (Una pasión inútil),” in COMBARROS-PELÁEZ, César (ed), Realismos contra la realidad (El cine español y la generación literaria del medio siglo), Semana Internacional de Cine de Valladolid, Cahiers du Cinéma España, 2011, p. 111-114.

BANDÍN-FUERTES, Elena, “‘Unveiling’ Romeo and Juliet in Spanish Translation, Performance and Censorship,” in CERDÁ, Juan F., Dirk DELABASTITA and Keith GREGOR (eds.), Romeo and Juliet in European Culture, John Benjamins, 2017, p. 197-226.

BARRIOS, Richard, West Side Story (The Jets, the Sharks and the Making of a Classic), Philadelphia, Running Press, 2020.

BARRIOS, Federico, “Interview with Author,” Barcelona, 16 February 2020. Unpublished.

BENET, Vicente J., El Cine Español (Una Historia Cultural), Barcelona, Paidós Comunicación, 2012.

BENPAR, Carlos, Rovira-Beleta. El Cine y el cineasta, Barcelona, Editorial Laertes, 2000.

BERSON, Misha, Something’s Coming, Something Good: West Side Story and the American Imagination, Milwaukee, Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2011.

BESAS, Peter, Behind the Spanish Lens (Spanish Cinema Under Fascism and Democracy), Denver, Arden Press, INC, 1985.

CATÁ, Joan, “‘Los Tarantos’, de Rovira Beleta, es projecta avui a l’Opéra de París,” Avui, 29 January 1990.

CERTEAU, Michel De, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London, University of California Press, 1988.

CORTÉS, Emilio Israel, “Cine Gitano en España: Antes y después de Los Tarantos (Reflexión necesaria),” Cuadernos Gitanos, 4, Instituto de Cultura Gitana, 2009, p. 37-41.

DAZA-CASTILLO, Juan José, 75 Años de Estrenos de Cine en Madrid (Tomo III) 1959-1963, Madrid, Ediciones La Librería, 2016.

DAZA-CASTILLO, Juan José & GÓNGORA-GARCÍA, Carolina, “Interview with Author,” Madrid, 20 December 2019, Unpublished.

DELEUZE, Gilles, Cinema I: The Movement-Image, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, London/Oxford/New York/New Delhi/Sydney, Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2018.

DELEUZE, Gilles, Cinema II: The Time-Image, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, London/New York/Oxford/New Delhi/Sydney, Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2020.

FERNIE, Ewan, Shakespeare for Freedom, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

FOULKES, Julia L., A Place for US (West Side Story and New York), Chicago/London, The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

HERRERO, Carlos F., “Prólogos (Realismos contra la realidad),” in COMBARROS-PELÁEZ, César (ed), Realismos contra la realidad (El cine español y la generación literaria del medio siglo), Semana Internacional de Cine de Valladolid, Cahiers du Cinéma España, 2011, p. 13-17.

“Hitos-Cine Paz,” Cinepazmadrid, URL.

HUERTAS-MARTÍN, Víctor, “Review of West Side Story, Produced by Som Produce (Teatro Calderón, Madrid, 22 December 2018; Teatre Tívoli, Barcelona, 14 February 2020)”, Sederi Yearbook, 2020, Forthcoming.

KOTTMAN, Paul A., “Defying the Stars: Tragic Love as the Struggle for Freedom in Romeo and Juliet,” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 63, n°1, 2012, p. 1-38.

LEHMAN, Ernest, West Side Story (Screenplay by Ernest Lehman), Booklet in 2003 Double-Disc edition of West Side Story, 1960.

Los Tarantos, dir. Francesc Rovira-Beleta, Tecisa, Films Rovira-Beleta, 1963.

MADRID-BRITO, Débora, “‘Por un antiguo agravio’: Los Tarantos y sus referentes literarios,” Revista Latente, vol. 9, 2011, p. 89-106.

MONTOLIÚ, Pedro, Madrid (De la dictadura a la democracia, 1960-1979), Madrid, Sílex Ediciones, S.L., 2017.

No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta, Dir. Alfonso Paso, Exclusivas Floralva Producción/Copercines, Cooperativa Cinematográfica, 1969.

ORDOÑEZ, Marcos, Un jardín abandonado por los pájaros, Barcelona, El Aleph Editores, 2013.

PILKINGTON, Ace G., “Zeffirelli’s Shakespeare,” in DAVIES, Anthony and Stanley WELLS (eds), Shakespeare and the Moving Image (The Plays on Film and Television), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 163-179.

QUINTANA, Ángel, “West Side Story,” Punt Diari (Gerona), 12 September 1985.

REGUANT, Ricard, “West Side Story 1996,” Ricardreguant, Blog, 28 March 2010, URL.

ROTHWELL, Kenneth, A History of Shakespeare on Screen (A Century of Film and Television) (Second Edition), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

ROVIRA-BELETA, Francesc, Los Tarantos, Film Dialogues, 1963, Manuscript available at Filmoteca Nacional de España.

SECRETARIADO INTERNACIONAL DE PUBLICACIONES Y ESPECTÁCULOS (SIPE), Guía de Estrenos 1963 VIII, Cuesta de Sto. Domingo, 7, Madrid-13, 1963.

TORREIRO, Casimiro, “¿Una dictadura liberal? (1962-1969),” Historia del Cine Español (Fourth Edition), in GUBERN, Román, José Enrique MONTERDE, Julio Pérez PERUCHA, Esteve RIAMBAU and Casimiro TORREIRO (eds), Cátedra (Signo e Imagen), 2004, p. 295-340.

SOM PRODUCE, “Aniversario del Estreno,” Westsidestory, n/d, URL.

VAL, Talía del, “Interview with Author,” 20 August 2020, Unpublished.

West Side Story, Dir. Jerome Robbins/Robert Wise, The Mirisch Corporations & The Seven Art Productions, 1961.

Notes

1 This article is subscribed to the research project “Teatro español y europeo de los siglos XVI y XVII: Patrimonio y bases de datos” (EMOTHE) of the University of Valencia (PID2019-104045GB-C54). Acknowledgements are owed to Jesús Tronch Pérez, to the personnel of Filmoteca Nacional de España, of Filmoteca Nacional de Catalunya and of the Biblioteca Nacional de España. Additional thanks are owed to Carolina Góngora-García and to Juan José Daza-Castillo (Cine Paz) as well as Talía del Val and Federico Barrios (Som Produce) for their collaboration in interviews. Special thanks are owed to Olga Escobar-Feito, Joaquín Roselló and Enrique R. del Portal for taking part in many conversations about West Side Story, Los Tarantos and No somos ni Romeo ni Julieta.

2 Misha Berson, Something’s Coming, Something Good: West Side Story and the American Imagination, Milwaukee, Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2011, p. 2.

3 For resemblances between the first two adaptations, see Courtney Lehmann, Screen Adaptations: Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’: The Relationship Between Text and Film, London/New Delphi/New York/Sydney, Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2010.

4 Kenneth Rothwell, A History of Shakespeare on Screen: A Century of Film and Television, Second Edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 128.

5 Ace G. Pilkington, “Zeffirelli’s Shakespeare,” in Davies, Anthony and Stanley Wells (eds), Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 172.

6 Richard Barrios, West Side Story (The Jets, the Sharks and the Making of a Classic), Philadelphia, Running Press, 2020, p. 15.

7 Ricard Reguant, “West Side Story 1996,” Ricardreguant, Blog, 28 March 2010. URL, accessed on 1 August 2020.

8 Víctor Huertas-Martín, “Review of West Side Story. Produced by Som Produce (Teatro Calderón, Madrid, 22 December 2018; Teatre Tívoli, Barcelona, 14 February 2020)”, Sederi Yearbook, 2020. Forthcoming.

9 “WEST SIDE STORY, en la version original de Broadway,” Youtube, 29 October 2018, URL.

10 Victor Huertas-Martín, forthcoming review.

11 Som Produce, “Aniversario del Estreno,” Westsidestory, n/d, URL.

12 Vicente J. Benet, El Cine Español (Una Historia Cultural), Barcelona, Paidós Comunicación, 2012, p. 17-18.

13 Carlos F. Herrero, “Prólogos (Realismos contra la realidad)”, in César Combarros-Peláez (ed.), Realismos contra la realidad (El cine español y la generación literaria del medio siglo), Semana Internacional de Cine de Valladolid, Cahiers du Cinéma España, 2011, p. 16.

14 Juan J. Daza-Castillo, 75 Años de Estrenos de Cine en Madrid (Tomo III) 1959-1963, Madrid, Ediciones La Librería, 2016, p. 13.

15 Anonymous, “Aires Nuevos”, Otro Cine, Año XII, March-April 1963, p. 243.

16 Elena Bandín-Fuertes, “‘Unveiling’ Romeo and Juliet in Spanish Translation, Performance and Censorship,” in Cerdá, Juan F., Dirk Delabatista and Keith Gregor (eds.), Romeo and Juliet in European Culture, John Benjamins, 2017, p. 197-226.

17 Ewan Fernie, Shakespeare for Freedom, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 49-51, and p. 57.

18 Ibid., p. 208-209.

19 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London, University of California Press, 1998, p. 117.

20 Id.

21 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, London/Oxford, Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2018, p. 5.

22 Ibid., p. 5.

23 Id.

24 Id.

25 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, London/New York/Oxford, Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2020, p. 8.

26 Ibid., p. 177-179.

27 According to Juan José Daza-Castillo and Carolina Góngora-García, “Interview with Author”, Madrid, 20 December 2019, Unpublished.

28 Secretariado Internacional de Publicaciones y Espectáculos (SIPE), report, Guía de Estrenos 1963 VIII, Cuesta de Sto. Domingo, 7, Madrid-13, 1963, p. 65.

29 Id.

30 Talía del Val, “Interview with Author,” 20 August 2020, Unpublished.

31 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall, Berkeley/Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1988, p. 102.

32 Federico Barrios, “Interview with Author”, 16 February 2020, Unpublished.

33 Julia L. Foulkes, A Place for US: West Side Story and New York, Chicago/London, The University of Chicago Press, 2016, p. 4.

34 Angel Quintana, “West Side Story”, Punt Diari (Gerona), 12 September 1985.

35 Marcos Ordoñez, Un jardín abandonado por los pájaros, Barcelona, El Aleph Editores, 2013, p. 95-96.

36 Deborah Madrid-Brito, “‘Por un antiguo agravio’: Los Tarantos y sus referentes literarios,” Revista Latente, vol. 9, 2011, p. 91.

37 Catá, Joan, “‘Los Tarantos’, de Rovira Beleta, es projecta avui a l’Opéra de París,” Avui, 29 January 1990, Page unknown.

38 Secretariado Internacional de Publicaciones y Espectáculos (SIPE), Guía de Estrenos 1963 VIII, Cuesta de Sto. Domingo, 7, Madrid-13, 1963, p. 309.

39 Asier Aranzubia-Cob, “Los Tarantos de Francisco Rovira-Beleta (1963) (Una pasión inútil),” in César Combarros-Peláez (ed), Realismos contra la realidad (El cine español y la generación literaria del medio siglo), Semana Internacional de Cine de Valladolid, Cahiers du Cinéma España, 2011, p. 114.

40 Emilio Israel Cortés, “Cine Gitano en España: Antes y después de Los Tarantos (Reflexión necesaria),” Cuadernos Gitanos, 4, (2009), p. 39.

41 Michel de Certeau, op. cit., p. xxiv.

42 Ibid., p. 99.

43 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II, op. cit., p. 33.

44 Id.

45 Ibid., p. 178.

46 Ibid., p. 137.

47 Michel De Certeau, op. cit., p. 104.

48 Ibid., p. 81-83.

49 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II, op. cit., p. 284.

50 See Carlos Benpar, Rovira-Beleta. El Cine y el cineasta, Barcelona, Editorial Laertes, 2000, p. 103.

51 Ernest Lehman, West Side Story (Screenplay by Ernest Lehman), Booklet in 2003 Double-Disc edition of West Side Story, 1960, p. 124. Virtually, these lines were taken from Arthur Laurent’s original play.

52 Francesc Rovira-Beleta, Los Tarantos (Film Dialogues), 1963, p. 30, Manuscript available in Filmoteca Nacional de España.

53 Pedro Montoliú, Madrid (De la dictadura a la democracia, 1960-1979), Madrid, Sílex Ediciones, S.L., 2017, p. 326.

54 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I, op. cit., p. 277.

55 Vicente J. Benet, El Cine Español, p. 326.

56 Ibid., p. 323.

57 In fact, parts of West Side Story’s soundtrack were played on the stage production of Paso’s NSRJ.

58 Michel de Certeau, op. cit., p. 97-98.

59 Ibid., p. 278.

60 Casimiro Torreiro, “¿Una dictadura liberal? (1962-1969),” in Román Gubern, José Enrique Monterde, Julio Pérez Perucha, Esteve Riambau and Casimiro Torreiro (eds.), Historia del Cine Español (Fourth Edition), Cátedra (Signo e Imagen), 2004, p. 297-299.

61 Paul Kottman, “Defying the Stars: Tragic Love as the Struggle for Freedom in “Romeo and Juliet”,” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 63, n°1, 2012, p. 6.

62 See Hugh Grady, Shakespeare and Impure Aesthetics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009; Helfer, Rebeca, “The State of the Art,” in Lupton, Julia Reinhard (ed), Romeo and Juliet (A Critical Reader), London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney, Bloomsbury, 2016, p. 79-100; Liebler, Naomi Conn, “‘There is no world without Verona Walls’: The City in Romeo and Juliet,” in Dutton, Richard and Jean E. Howard (eds), A Companion to Shakespeare’s Works, Volume I: The Tragedies, Malden, MA, Blackwell, 2003, p. 303-318.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Víctor Huertas-Martín

Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)