- Accueil

- > L’Oeil du Spectateur

- > N°8 — Saison 2015-2016

- > Adaptations scéniques de pièces de Shakespeare et ...

- > Edouard II (Edward II), translated by André Markowicz, directed by Guillaume Fulconis, Le Ring Théâtre, Festival du Village, Brioux, 2-4 July 2016.

Edouard II (Edward II), translated by André Markowicz, directed by Guillaume Fulconis, Le Ring Théâtre, Festival du Village, Brioux, 2-4 July 2016.

Par Stéphanie Mercier

Publication en ligne le 11 juillet 2016

Texte intégral

1Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II (circa 1594) reads (at least in its modernised “Penguin Classics” version1) like a television series script. Hard-hitting style and strained relationships create dramatic tension that revolves around, not wide-sweeping historical events, but suffocating power struggles with both gender and genealogical issues at stake. Because of his all-consuming masculine love interest – Gaveston (Kévin Sinesi) – Edward (Côme Thieulin) alienates the narrow-minded English court’s barons. The even bigger problem, however, is the king’s favourite’s lowly status and subsequent promotion that threaten not only sexual, but also social, order. All these private and public aspects of Marlowe’s play were definitely taken out of the closet and pushed into the open in this excellent production by the pithy and enthusiastic Ring Théâtre2 – in both a figurative and literal sense here as the play was adroitly performed in a Brioux’s inhabitant’s borrowed back garden. Moreover, the unusual locus enabled for a reinforced rather than a diminished take on Marlowe’s sardonic script that seemed all through destined to disclose the pettiness in politics : calling into question the legitimacy of past and present ruling classes as it did so.

2 Indeed, cogent perception was more than merely fictional. Intellectual command of the plot and its mechanisms was at the forefront of the production. For instance, actors and their character(s) were immediately presented orally to at once provide an impactful close-up on English history and the mind set of Shakespeare’s contemporary for a French audience most probably unacquainted with either. The wonderfully testosterone-filled barons – Warwick (Sébastien Bonneau), Mortimer (Cantor Bourdeaux) and Lancaster (Julien Testard) – had their names blazoned, not on traditional doublet and hose, but on American football shirts that gave an accurate impression of their pugnaciousness whilst being an as equally convenient cue to their identities. Place names appeared as successive illuminated signs that directed audience attention to spatial changes despite the static set. The play’s director, Guillaume Fulconis, even came on stage himself, to play Arundel, or maintain dramatic momentum mid-way through by explaining, rather than directing, the action of Gaveston’s and Lady Margaret’s (Amélie Esbelin) marriage, Edward’s departure for Tynemouth (Scene VIII) or Gaveston’s murder at the hands of Warwick (Scene VIIII). Further, the episode involving Sir John of Hainault (Scene XV) was personified by a member of the troupe (Julien Testard) as a brilliant parody of an academic, who resembled one of the popular comic François Damiens’s many personalities – complete with Belgian accent, gags and pedagogical slide show, including one of typical beer and chips – in a highly successful theatrical bid to bring alive a tiny, and yet vital, detail in the original script that could have otherwise have passed-by unnoticed for a modern-day public.

From left to right : Warwick (Sébastien Bonneau), Lancaster (Julien Testard), Mortimer (Cantor Bourdeaux)

©Yves Petit

3The clarification of other theatrical tricks was just as innovative. Interior objects (washing machine, locker…) were exposed on a scaffold above which the light and sound engineers (Elias Farkli and Quentin Dumay) were perched, whilst a caravan that served as either dressing room, sound studio or Lady Margaret’s castle stood on the other side of the stage. Between the two was hung a curtain with a landscape painted on it that provided a diegetic backdrop or, in Scene XI, a front screen for an extremely efficient shadow theatre of the civil conflict provoked by Gaveston’s murder. In this instance, the handful of actors apparently became multitudinous characters with the barons still recognisable by their shoulder pads, Edward’s victorious soldiers spurred on by what seemed like hordes of longbow men and ominous extra-diegetic music or sound effects to accentuate the horrors of a war that was aurally as well as visually experienced. On a lighter note, the running joke that involved false blood being liberally spurted over actors’ clothes in the murder scenes – the troupe’s dresser (Gwladys Duthil) then pointedly removed and laundered the stained clothes in the washer – provided comic relief whilst highlighting the ephemeral nature of a duplicitous existence that Marlowe must have been aware of as a playwright or, as legend has it, because of his activities as a spy. The production’s tongue-in-cheek intent was thus made plain from the outset. The metatheatrical elements of the mise-en-scène enabled the production at once to point backwards, to an already imagined English history, and forwards, with unshrouded pragmatism, to the modern French elucidation of Marlowe’s play.

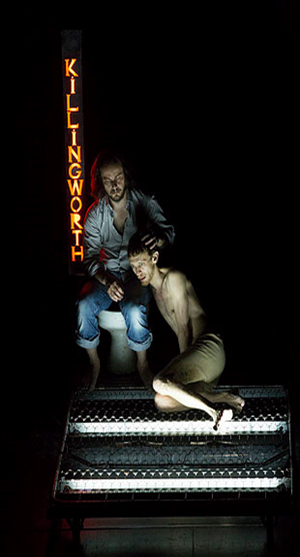

4Another achievement of the production was undeniably the interpretation of the essentially English characters by the all-Gallic cast. Because it was consistently foppish, the performance of Edward was outstandingly majestic. The king’s unswerving solipsism with regards to his relationship with Gaveston, and then the younger Spencer (Sébastien Hoen-Mondin) credibly metamorphosed into a sacrificial, albeit narcissistic, Christ-like posture : although material altruism inexorably dominated generosity of a mystical sort. When there were no more titles to tender and as the king awaited his death in Killingworth – figured as a wire mattress upon which was positioned a vertical neon town sign and a toilet – came the abdication scene (XXII), almost a parody prequel to that of Shakespeare’s Richard II. It was here that Edward, having been shaved and dunked in sewage water, eventually gave up his crown to Leicester (Julien Testard) appropriately sitting trousers down on what had become the physical manifestation of the caricature of a throne. The king’s subsequent murder – sandwiched here between two giant pillows topped with an ironing board as Lightbourne (played by Kévin Sinesi, who was cast both as the king’s lover and murderer, thus providing an effective physical link between Eros and Thanatos) thrust a red-hot poker up Edward’s backside whilst the power-drunk, mafia-suited, sunglass-toting Mortimer played jazz on a saxophone to the light and sound engineers’ accompanying guitars – made explicit connections to the original text whilst hailing other forms of dramatic expression that pointed, at once to the possible invention of the modus operandi of the king’s death by historical writers, as well as more modern methods of portraying death on stage or screen.

From top to bottom : Gaveston (Kévin Sinesi), Edward (Côme Thieulin)

©Yves Petit

From top to bottom : Leicester (Julien Testard), Edward (Côme Thieulin), Gurney (Sébastien Bonneau), Lightbourne (Kévin Sinési), Matrevis (Julien Testard)

©Yves Petit

5Even the French Queen Isabella’s (Lucie Rébéré) potentially difficult transformation from child-bride to conspirator was adroitly enacted here. She was first seen as infant, in a girlish dress and flat shoes, to be forcibly married to Edward and yet remain ingenuously optimistic over their union until the revelation of her husband’s extra-marital infatuation (Scene IV). The two male lovers, instead of exchanging pictures (IV. 127), exchanged kisses, whilst undressing and the king then sat on his man friend’s lap in embrace – his wife looking on all the while. The monarch’s love-crazed mind even compelled him to make his wife give up her throne to his favourite whilst she was glibly termed a “French strumpet” (IV. 145) : details that plausibly led her to nostalgically sing the Charles Trenet song Douce France before crossing, not The Channel, but over to the belligerent Mortimer’s camp. The latter’s muscle flexing at her wedding and subsequent show of daring opposition to Gaveston’s influence over the king also credibly led to the spiritual conversion becoming physical in this instance – the pair shut themselves in the lockers to “talk apart” (IV. 229) after which the queen reemerged in tight dress and high heels in a visual statement of growing confidence that would ultimately lead to her giving the order for her husband’s murder (XXII. 45) and defying her own son, now Edward III (Charlotte Dumez), by the play’s close. The latter character’s own staged presence – as an on-stage physical expression of an as-yet unconceived child at the play’s beginning to a self-aware monarch by its close – was masterly performed in a cross-over manner by Dumez. After first appearing as simply boy-like, he/she sang Shakespeare’s Sonnet 144 (“Two loves I have, of comfort and despair…”) in English mid-way through, before finally adopting the barons’ American football kit livery to bloodthirstily train for revenge for Mortimer’s treachery.

From top to bottom : Guitars (Elias Farkli and Quentin Dumay), Mortimer (Cantor Bourdeux), Queen Isabella (Lucie Rébéré), Edward III (Charlotte Dumez), Warwick (Sébatein Bonneau)

©Yves Petit

6Before lights went down a final tableau depicted Dumez as the new king, next to Edward II’s English flag draped coffin with Mortimer’s head figured by a golden, yet battered, football helmet on top. Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary played : ending the production with an outwardly melancholic pointer to the ephemeral nature of power on earth. And yet, some spectators may have remembered that an electronic version of the March also featured in Kubrick’s film, A Clockwork Orange, suggesting that, depending on our capacity for a suspension of disbelief, transient physical supremacy can be infinitely revived in scriptural, musical, scenic or screened forms. Here, all forms joined in association to successfully reinvigorate the legitimacy, if not of politicians, most certainly of Marlowe’s wonderfully sardonic plot.

Notes

1 Christopher Marlowe, Edward II, in Christopher Marlowe : The Complete Plays, ed. Frank Romany and Robert Lindsey, London, Penguin Books, “Penguin Classics”, 2003. All quotes are from this edition.